Tailor of Inverness, The (16 page)

Read Tailor of Inverness, The Online

Authors: Matthew Zajac

I’m immediately led through the grand foyer, past rows of actors’ headshots and a huge bust of Shevchenko, up to the circle, on to the upper circle and into a gallery at the side of a vast marbled and chandeliered hall. Everywhere is either unlit or only dimly lit, except this small gallery. I climb the steps up to it and I’m greeted by a long table, on it a lavish spread of food and drink and, crammed around it, the festival elite, around twenty five people, who all look up as we enter.

Mykhaylo introduces me. I feel a little daunted, a little like an interloper. Here are the festival judges, professors, actors, directors, critics, a high-ranking civil servant in the culture ministry, guests from Macedonia and, at the opposite end of the table, Robert Longthorne and Rebecca Ross from the Liverpool Everyman and Playhouse Theatres. Mykhaylo leads me down to sit near them and I greet them with some relief. Sitting beside them is Sasha Papusha, a debonair actor from the Shevchenko’s ensemble and a fluent English speaker. I sit and join the proceedings. My arrival has briefly interrupted the toasting. I welcome the opportunity to eat, relax and drink but the overwhelming torrent of new people and places coupled with physical tiredness proves to be a dangerous combination.

I’m eager to bond with these people, to accept their hospitality, to join the party. The

horilka

(vodka) flows and I don’t hold back.

I’m garrulous, excited and fascinated by the gallery of characters before me. One or two of them eye me with suspicion, most are smiling and welcoming. Within an hour, I’m tipsy, within two, I’m drunk and we go on toasting each other and talking, comparing working conditions and

productions

in our respective countries, explaining aspects of our histories, singing the odd song. The party breaks up at 2am and I’m staggering. I’ve been rash. I haven’t even checked in to the hotel. My bags are – where? Ah, there they are! Yuri is looking after me. Rebecca, Robert and I are escorted through the streets to the hotel, a five-minute walk, though I can’t really tell. Yuri carries my holdall and we make it to my room. Yuri dumps the bag and bids me good night. I trip over my bed and fall on my face, cracking my neck. And after all that, it takes me an hour or so to get to sleep, images and sounds of the day racing about in my head.

I wake at 10.30 with an appalling hangover. I lift my head towards the window and immediately let it fall back onto the pillow, a sharper pain shooting up from my neck. I remember the fall and lie there, prone, for an hour, dozing, groaning, staring at the ceiling and recalling the events of the previous day: Captain Roman, the welcoming party on the platform, the American banker, the line of carriage lights through my video lens, my silent escort Bogdan, the long, laden table, the ugly airport hotel I stayed at in Manchester, the toasting, the vodka, the drunkenness. The alphabet. I’ve got to get on top of that. Д = D, П = P, Ц = TS, Я = YA. I listen to the sound of chambermaids along the corridor, unlocking doors, calling to each other. So I’m here.

I rise and look out of the window. Before me is a lake, 2 or 3 kilometres long, kidney-shaped. It’s surrounded by trees,

a busy road on one side, a tall church with an onion dome and buildings in the distance. I’m parched. I have a water bottle. I take a shower and, afterwards, feel a little better, but I still feel like shit. Fortunately, it’s the only hangover I’ll have in Ukraine. My body adjusts quickly to the vodka intake and, for the remainder of my stay, I’ll retain a certain manageable level of pickling.

I get dressed and wander out. It’s a fine day, with a little autumn chill in the air. I cross the wide road in front of the hotel and walk through a well-kept square of rectangular lawns, flowerbeds, trees and paved walkways. There’s a large bronze statue of a horseman, the Hetman Halitsky, who founded Lviv. I pass a couple of stalls selling second-hand books and jewellery, some smart-looking shops and cafes and an impressive, ornate Greek Catholic Cathedral with white marble walls and copper domes. I come to a much larger square. Off to the left is the grand Roman façade of the theatre, a huge tarmac apron spread before its steps. I’m hungry. I retrace my steps and stop at the Café Europe where I eat a large lunch of borscht, lamb cutlets, potatoes, cucumbers and carrot & cabbage salad. It’s delicious and very cheap, for me. I’m a rich tourist.

This trip’s the wrong way round. I should be with my relatives first. The theatre festival should come later, but I’m obliged to attend. I want to and the Scottish Arts Council has been kind enough to pay for my attendance. I ring Mykola and Xenia and we manage a basic conversation. I’m in no fit state to visit them, so I promise to go tomorrow. The hangover is gradually improving, but it’s still all I can manage to get back to the hotel, where I lie down for another hour before the commencement of the day’s performances and the

subsequent

cultural celebration, or piss-up.

When I rise, I make my way to the Young People’s Theatre, its façade decorated with metallic birds and a figure who could

be Pinocchio. The auditorium seats 300 and it’s full for the afternoon presentation of

Marriage Play

by Edward Albee, presented by the Dramski Theatre of Skopje, Macedonia. The play is a profound, unsentimental dissection of marriage and mid-life crisis. It’s given an excellent production. The two actors received an award for their outstanding work at the end of the festival.

After the performance, I have time to grab something to eat before sitting down in the main auditorium of the Shevchenko Theatre for

It Was Not To Be

by the Ukrainian dramatist Mychaylo Staritsky. This is the main presentation by the host company and the first Ukrainian play I have ever seen. Written at the turn of the last century, it’s a moving story of two young lovers and the loss of innocence. Mychaylo is the son of wealthy, educated Ukrainian landowners with

aspirations

for greater wealth and social position. They speak in Russian and French, scorning the Ukrainian of the peasants. Mychaylo is idealistic, hoping for a more egalitarian society. He wears peasant clothes and speaks in their language. For this, he is mocked by his family.

Katerina is a peasant’s daughter, beautiful and demure, aware of her low position in the social structure. She has a suitor, a peasant boy Dymytro. Convention demands that they should marry. But Mychaylo and Katerina fall in love. News of the affair spreads quickly through the community. Mychaylo’s parents want to send him away to St. Petersburg. Katerina’s mother warns her to keep away from Mychaylo and that she should be content with Dymytro, but Katerina becomes pregnant to Mychaylo. She doesn’t tell him. The censure of his family and the larger community begins to wear Mychaylo down. He tells Katerina that they must meet only in secret. This angers her and she believes that he is ashamed to be seen with her. She becomes depressed. Mychaylo’s cousin tells him that he can persuade his parents to accept Katerina and that

it will be easier for him to do so if Mychaylo leaves for St. Petersburg. Mychaylo agrees, desperate for a resolution. Instead, the cousin offers Katerina money to leave the region for good. With Mychaylo gone, she plunges into despair and commits suicide.

Written towards the end of Stanislavski’s tenure at the Moscow Arts Theatre where his work with Anton Chekhov had become famous, the play draws on Chekhov’s naturalistic style and puts it firmly in a Ukrainian setting, acutely satirising the efforts of the Ukrainian bourgeoisie to mimic their

aristocratic

Russian rulers. There is a clear political aspect to the play as it focusses on these tensions and on the class divide with a Ukrainian nationalist slant. Staritsky obviously felt great warmth towards the Ukrainian peasantry, although their portrayal is not sentimental: their condemnation of the lovers is as strong as that of the rich family and Katerina’s mother forcefully attempts to maintain the status quo by urging Dymytro’s suit.

It’s a well-structured play, given a powerful production by Slava Kila, the most impressive I saw at the Ternopil Theatre Festival. The acting of the large ensemble is uniformly excellent, muscular and spontaneous. It includes beautifully

choreographed

sequences depicting peasant life. Andriy Malinovitch and Svitlana Prokpova are outstanding as the lovers. A simple and effective set featured a sloping scrim backdrop, backlit for strikingly poignant scenes where the shadows of peasant children at play and girls dancing provide a counterpoint to the main action. A skeletal, solitary tree and an upright spiked pole, around which haystacks are built, complete the set.

The production is marred, however, by an aspect of life here which I can’t relate to, arising in a sub-plot: the subject of anti-semitism. Mychaylo’s father wants to get his hands on the land of two small independent Ukrainian farmers. He goes about this in league with a Jewish middleman, a greedy,

conniving character. At another point in the play, the estate manager picks up a cigarette butt and sniffs it. ‘Jew!’ he says, crushing it with his boot, to which many people in the audience laugh.

In conversation after the production, members of the company are unwilling to accept that there is anti-semitism in the play, saying that it simply offers a truthful portrayal of the position of Jews as middlemen in Ukrainian society at that time and that this should be understood in its context. Nevertheless, when I ask one of the actors if there are any Jews working at the theatre, I’m told that there aren’t and that if there were, they wouldn’t admit to being Jewish. The Ternopil Theatre aspires to take its work abroad. This

production

could sit comfortably in the programme of any International Theatre Festival in Western Europe, but for its derisory attitude towards Jews.

Sweet, stewed coffee poured with a ladle and a sweet bread bun. The

Staro Misti

of Ternopil, the Old Town. The hospitality is overwhelming at the nightly receptions of the Ternopil Vodka Festival, sorry

Theatre

Festival. Toasting into the small hours.

Kielbasa

, smoked salmon, pickled cauliflower, roast chicken, cucumbers, tomatoes and peppers, all to absorb the alcohol, water and beer to dilute it!

I met Roman, standing in for Sasha, our usual interpreter. Roman has a Canadian wife. He lived and worked there, legally, for nearly three years before they threw him out. His lawyers said he’d be back within three months. That was nearly two years ago. The Canadian authorities demand proof that his marriage is genuine, not a convenience to enable him to gain citizenship. How can they prove they love each other when they are forced apart? Repeated applications? $800 spent on phone calls in a few months? A baby?

Roman won’t make his wife pregnant when he doesn’t know if he’ll be there to support her and he doesn’t want his child brought up here in Ukraine, which is riddled with corruption and where healthcare, education and other public services are poor. He told me of a friend whose baby had a haematoma.

He had no money and the doctor refused to operate until he found some cash. It’s a straightforward operation. In the end, Roman’s friend told the doctor ‘I love my child and you love yours. If my child dies, one of yours will too.’ The doctor performed the operation immediately.

Roman works in a sauna. He and six or seven of his friends and acquaintances, all in their mid- to late-20s, hire the place for two hours every Saturday morning. Today is Saturday, so I go with him, fuzzy from too much alcohol and too little sleep. It’s a brand new private facility, run by another friend. It’s well appointed and clean, but expensive for ordinary people. It might function as a knocking shop, though I saw no signs of that. There are a couple of his old schoolmates here. Roman was once a wrestler and the others he met through wrestling.

We sit in the steam room and slap our bodies with bunches of birch and oak twigs, use the plunge pool and the showers and sit in the lounge, watching Champions League highlights (in English), drinking beer and herbal tea, smoking and chatting. England, Scotland, football, politics, gangsters. I ask if there are a lot of gangsters here. They laugh. One of the group, a small, dark-eyed, garrulous joker, gestures towards himself and a couple of his friends. ‘Yes, you’re looking at some!’ Everyone laughs. When we leave, Roman tells me that the joke is, in fact, the truth. The joker and his two friends are part of a gang which runs a protection racket.

We walk back to the hotel where I expect to meet Bogdan, but I’ve missed him. A chambermaid tells me he’s been twice. He’s left a plastic bag containing three huge red apples for me. I wait for an hour. No sign, so I take a taxi to a large 1970s apartment block on the edge of town, the home of Mykola and Xenia. While Xenia busies herself, putting the final touches to lunch, eager to please me and short of breath, I sit with Mykola. He is dignified and quiet, full of good humour, happy to welcome me. He is also partially deaf, blind

in one eye and showing signs of frailty, but he retains an upright posture and a very firm handshake. The living room walls are draped in tapestries, flower patterns and geometric peasant designs, all made by Xenia, family photographs and two of their favourite politicians, the nationalists Julia Tymoshenko and Viktor Yushchenko. A young man enters the flat, Marion the downstairs neighbour, a joiner who has a little English. We talk.

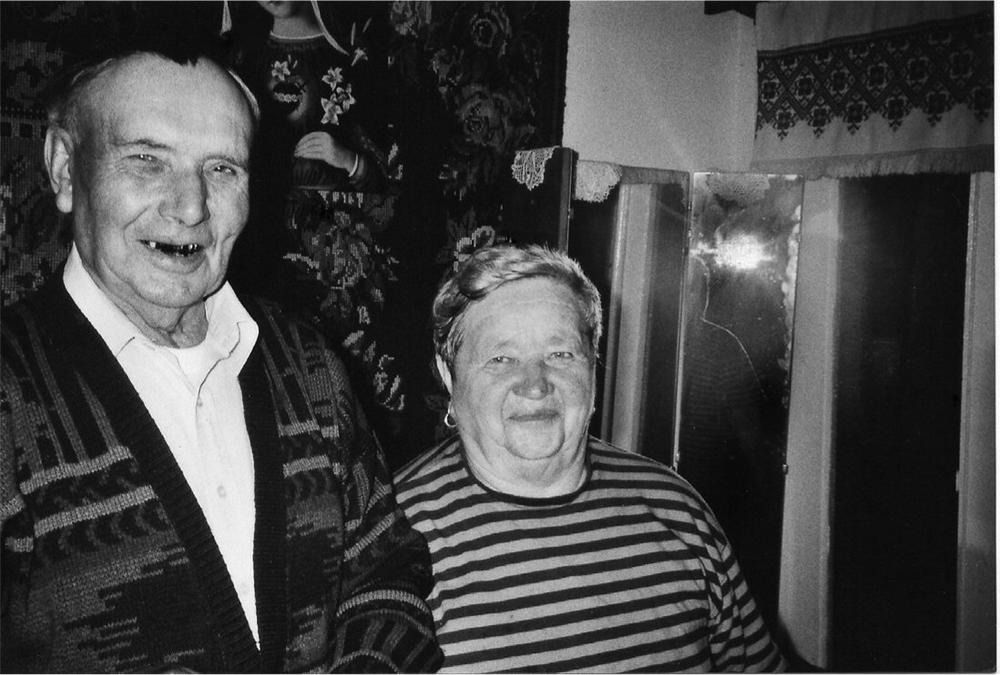

Mykola and Xenia Baldys, Ternopil 2003

Marion’s English is really very limited, not much better than my Ukrainian. Mykola shows me a tome which details histories of all the villages in the

oblast

. A few pages cover my father’s village, Gnilowody, a name which translates as Rotten Water, 8km from Podhajce. After the war, the Soviets renamed it Hvardiskoye, which means ‘garrison town,’ due to the fact that soldiers were stationed there at the time. It has since reverted to its original name. He and Xenia name my father’s family, his mother Zofia, who was Mykola’s aunt, his father Andrzej, and Kazik, Adam and Emilia, his brothers and sister.

Zofia, like Mykola and Bogdan, was born in the neighbouring village of Mozoliwka. Emilia had married Pavlo Tischaniuk, a Ukrainian farmer. They had a son, Teodosiy.

Then we talk about the war. Mykola presents me with a sheet of A4 paper, detailing what he knows. With Marion, he then tries to explain what it says. They slowly reveal a very different story to the one my father told me, a story which stuns me.

According to Mykola, my father was never in the Polish Army. He trained as a tailor, first in Mozoliwka, then in Podhajce, until 1940.

‘Then he was drafted into the Soviet Army.’

‘The Soviet Army? You’re telling me that my father was in the Soviet Army?’

‘Yes.’

Mykola looks to Marion for further translation. ‘In army of General Vlasov, commander.’

Mykola turns to look intently at me with his piercing blue eyes.

‘Vlasov?’

‘

Tak

. In Vlasov Army, Russian Army.’

‘My father was in General Vlasov’s Russian Army?’

‘

Tak

,

i Vlasov do Polsci i Niemcem

.’ He looks to Marion.

‘Er, Vlasov, to…Poland, Germany.’

‘Right, Vlasov…how do you mean Poland and Germany?’

Marion doesn’t answer. He is busily trying to translate the next sentence on Mykola’s testament. ‘Er….1944, August 1944, Soviet front River Strypa.’

‘

Piat kilometr Hnilowody

.’

‘Five kilometre from Gnilowody.’

‘Uh-huh…River Strypa.’

‘Your father in Germany in 1944.’

‘What, he was in Germany in 1944?’ I’m reeling.

‘Yes, and then in August on front on River Strypa.’

‘Was he a prisoner?’ I still can’t absorb what they are telling me.

‘

Ostarbeiter

.’ The name given by the Germans to forced labourers from the Soviet Union. ‘Then on the front’.

‘

Gorace kartoffle

! The potatoes are hot!’ Xenia’s

intervention

brings an abrupt halt to our progress.

‘I met your mother in Poland. She was very delicate and slim, and beautiful. Is she still?’

‘Yes, now not so slim.’

‘Your father and his brother liked a drink. Your mother is the same age as me. Anyway, the potatoes are hot! Time to eat.’

The afternoon continues as we turn to the delicious food and drink. We laugh and joke about our few shared memories of family and, by going over Mykola’s statement, I absorb the essentials. My father was drafted into the Soviet Army under Vlasov, was captured by the Germans, worked as a forced labourer in Germany, then fought for the Germans from summer 1944 here in Ukraine and during the German retreat. Vlasov is famous for being a turncoat, the highest ranking Soviet Officer to change sides. He surrendered his army to the Germans near Leningrad in 1941 and towards the end of the war led some of it against the Soviets, retreating all the way to Czechoslovakia. According to Mykola, my father was in a German Army unit which paused for a few weeks near Gnilowody, on the Strypa River, and my father managed to visit his family then, late at night. It was a very dangerous time. Mykola’s statement finally declares that this story was related to him by the man himself, by my father, when Mykola and Xenia met my parents in Poland in 1982.

If this is true, and I can’t think Mykola would have any reason to lie to me, then my father’s story is a complete

fabrication

. He told me that he had escaped from the Soviet Union through Stalin’s amnesty for Polish prisoners of war. Over

100,000 Polish soldiers escaped this way, along with around 30,000 Polish women and children, sailing across the Caspian Sea to Tehran. The soldiers were led by the Polish General Anders and became known as ‘Anders Army’. Could my father have simply absorbed the facts of Anders Army and then imaginatively adopted that army’s story as his own?

And if he had done this, what did he really do in the war?

If Mykola doesn’t have a motive for lying, my father did: fear. In Britain, Poles who fought on the German side kept quiet about it. They had been on the losing side and were afraid of being perceived and persecuted as Nazis or Nazi sympathisers. As tension between the western powers and the Soviet Union grew to hostility in the years following the war, membership of the Red Army could also have been viewed with suspicion. One of the myriad brutalities of World War Two was that the vast majority of soldiers in my father’s position had little choice but to do as they were ordered. The alternative was almost certain execution, either summarily or drawn out through the starved, frozen labour of the Soviet

Gulag

or the German

lager

.

But to have lived for decades with the pretence that he fought in the Polish Army and latterly the British Army, to have immersed himself in it to the extent that he could describe the journey in detail over a couple of hours, to deceive his own children and maintain the pretence with friends and acquaintances, customers and colleagues, takes determination and discipline. But then, as I reflect, there are a number of sketchy aspects to his story.

He was always vague about where the Russians took him to work; there’s actually very little detail about the journey to Egypt and the period he claimed to have spent in North Africa. But there is a lot about Italy, especially about his girlfriend there and her father. Didn’t he speak Italian? Yes, he did. What exactly happened to Vlasov’s Army when it was captured by

the Allies in 1945? Could it be that non-Russians in that army were taken west by the British and put to work in the Italian occupation? I recalled my chance encounter with the Ukrainian Paul Batyr as he was cutting his lawn in Lochend in Edinburgh. After his surrender, he was sent to work in Italy.

As I try to absorb Mykola’s revelations, he produces a book about the Ukrainian Partisan Army’s history during the war. I’m unaware of the existence of such an army, but quickly understand that it was established to fight for Ukrainian

independence

. I realise that there has to be a lot more to it than that and curse my ignorance. The book contains photographs of smiling bands of soldiers posing in front of their forest hideouts or on the march, leading horses with machine guns strapped to their backs. Mykola turns to pages which list the names of the dead and points to one of them. ‘

Tvoy kuzyn

. Your cousin.’ There on the page is Teodosiy’s name, killed by the Russians in 1944 at the age of 17 for his membership of the UPA.

I leave their house in a daze, full of good food and home-made vodka. Mykola accompanies me to a bus stop and sees me on to a packed minibus, telling the driver where I’m going. He waves me off with a smile and for a moment I wonder what his own war story was, but only for a moment. I’m upset, baffled, moved and angry. Why didn’t dad tell me at least? Was he so afraid that he distrusted his own son? Did he think I’d condemn him, or was he driven by guilt? What horrors had he been witness to, or even been a party to? Now, I couldn’t exclude even the worst possibilities. Now, there was a void in his history: those awful years of 1940-45. And that void could be filled with any number experiences endured by those unfortunate enough to be in the eye of the storm, in Central and Eastern Europe. Settling in a foreign country at the end of the war gave him the opportunity to wipe the slate clean, to go back to Year Zero, and that’s what he did.

He lived quietly and worked hard, putting everything into his new life and his family, looking after us with a great deal of love and humour. Only from time to time, when

All Our Yesterdays,

or

The World At War

or other evocations of the war were on TV, would I catch him wiping away a tear or, in the dead of night, when I’d hear him, muffled through the thin wall between our bedrooms, half-awake and restless or talking anxiously in his sleep, were hints of the turmoil and the shock of his war revealed to me. These thoughts race through my head as the minibus speeds through the streets of Ternopil, eventually depositing me in the city centre. I make my way once more to the theatre.

The show is

The Lady with the Little Dog

by Anton Chekhov presented by Theatre Atsurko na Zdorovska. This is another fine two-handed production for a man and a woman, an adaptation of one of Chekhov’s most famous short stories. It tells of an affair between Gurov, a rich, married womaniser and Anna Sergeyevna, a newly-married young woman. Both are unhappy with their marriages. Despite her shame and his self-loathing, they come to understand that they have truly fallen in love with each other and that ‘the most complicated and difficult part was only just beginning.’

The short, simple production had a cumulative power as the characters’ desire for each other and the strictures of their society reached a level of unbearable tension. This was acting of the highest order, both actors completely in tune with each other’s rhythm and pitch, giving the production the quality of a complex musical duet.