Taken by Storm (26 page)

Authors: Angela Morrison

Tags: #Social Issues, #Dating & Sex, #Christian, #Friendship, #Juvenile Fiction, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #Religious, #Water Sports, #Death & Dying

chapter 36

CHURCHED

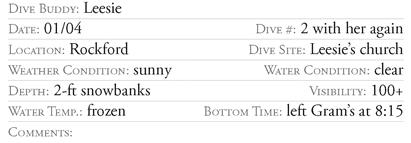

MICHAEL’S DIVE LOG—VOLUME #8

i wear the black pants and gray dress shirt we bought for the dance. Can’t get the tie right. Freak. It’s a Valentino. She doesn’t even own a cell. Her computer is an ancient desktop. And she bought me a vintage designer tie. And i, creep freaking jerk, threw it all away.

i get to Leesie’s late—park in the front, run up the steps, and ring the doorbell.

“Thought you’d chickened out,” she calls from the driveway, where she stands by the pickup with a set of keys in her hand. She wears a denim skirt, brown leather boots—not cowboy—a top i bought, and her damaged suede jacket. She runs down their curved gravel driveway and grabs Gram’s bunny key ring. “My family already left. Better let me drive.”

Leesie’s branch is in Rockford, the third dinky town up the highway toward Spokane. She whizzes along the road, doesn’t slow to 25 mph for the towns. “Small-town cops all sleep in Sunday morning.” She squeals off the highway, pulls up in front of a small white building.

“Stylish, huh.” She gets out of the car. “There’s not a lot of us out in the country, so we rent this Grange hall. It’s an old army barrack they had moved here.”

i don’t know or care what “Grange” is. The place screams “dump.” Nothing like the nice building her dance was in or her fancy wedding cake temple.

Leesie opens a heavy wood door, held together with repeated coats of blue paint. We pass through a foyer and into a room filled with rows of metal folding chairs, milling people, and loud, happy talking. A woman with gray hair plays hymns on a black upright piano. She pounds as hard as she can and keeps the pedal to the metal, trying to drown out the cheerful buzz.

“Thought we were late,” i whisper, hoping my breath tickles Leesie’s ear.

“We never start on time.” The cement floor is painted bright red, the walls a dull green. Works for Christmas, but what do they do on the Fourth of July?

“Want me to hang up our coats?”

She shakes her head. “Furnace doesn’t work too well.” She holds my hand loosely to guide me through the buzzing Mormons, says hello, to people, doesn’t mess around introducing me.

Her mom and Stephie have a row of chairs saved. “Those seats are for you.” Stephie points to the places on the end. “These are for Dad and Phil.” She braves the chill to show off her flowery dress with a red velvet collar and headband to match.

i sit down, tighten my fingers around Leesie’s so she can’t let go of my hand. There’s maybe forty people total in the room, lots of them kids. i catch sight of Phil, wearing a navy suit, a white shirt, and a tie covered with leering Tasmanian devils. He’s on his feet at the front of the room, placing rectangular trays full of tiny white cups on a table covered with a white tablecloth. Leesie’s dad, wearing almost the exact same suit and white shirt—with a more cautious tie—helps him cover the trays with a white embroidered cloth. They both sit down behind the table.

i don’t know what i’m doing here or how this can help me figure out what to do with my parents’ ashes. The place is bedlam, but i’d agree to sit just about anywhere with Leesie’s fingers wrapped around mine. Do friends hold hands?

The piano music stops. A big man in his fifties, red-faced and balding, stands up. “Brothers and sisters, can you take your seats.”

The buzzing trails off. Everyone sits down. They sing a hymn. They all bow their heads. Leesie drops my hand to fold her arms. A woman prays, short and in her own words. Leesie’s soft, “Amen,” mingles with the others.

A pleasant feeling comes into the room. Surprises me. i don’t feel condemned, sitting with the holies. They call themselves “saints,” but they seem like everyday families, kids and parents and a handful of old ladies. i relax, leaning slightly against Leesie’s shoulder.

The red-faced guy says some more stuff. Everyone raises his or her right hand and then puts it down. It looks like voting, but no one votes no. Then they sing again. i like listening to Leesie sing. She has a pretty voice, holds the book so i can follow the words. Not that i even consider joining in. During the song, Phil and Leesie’s dad are up front, standing behind the table covered with white cloths, breaking bread into little pieces. A couple of pudgy junior-high-age boys wearing rumpled white shirts and baggy tan Docks stand in front of the table.

“This is the sacrament,” Leesie whispers when the song is over.

Phil kneels down in front of the table, reads a prayer, more

amen

s, and then he and his dad give small trays full of the broken bread to the junior high boys and they pass it around. When it gets to us, Leesie breathes, “You don’t take any,” into my ear.

amen

s, and then he and his dad give small trays full of the broken bread to the junior high boys and they pass it around. When it gets to us, Leesie breathes, “You don’t take any,” into my ear.

i wish she’d take my hand again. It’s getting cold, but i don’t shove it into my coat pocket. i let it hang down where she can find it.

A baby starts to cry. The mother hurries out with it. Then Leesie’s dad kneels and prays, and the boys are at it again, this time with water. i touch Leesie’s hand as i pass the tray to her. Each tiny cup rests in its own hole. Four long rows. Leesie drinks a cup, drops the empty into a hole in the tray. The bottom’s enclosed, holds the used cups out of sight.

Leesie passes the tray on to her mom, then glances back at me. She closes her eyes, bows her head. i feel her warm fingers winding around my cold ones. i slip both our hands into my coat pocket. Church isn’t all that bad. Leesie glances sideways at me and then bows her head again.

When the passing is over, Mr. Red Face stands up and tells the guys to go sit in the congregation with their families. Phil and Leesie’s dad take their seats. Stephie slides over so she can sit between them. Leesie’s dad glances at Leesie and me. He must see her hand disappearing into my pocket.

Red Face tells a story about answering his secretary’s questions about “the Gospel.” He says he knows this church is the only true church on earth and sits down.

Leesie leans over and whispers, “This is fast-and-testimony meeting. We normally have assigned speakers.”

“Which one’s the minister?” Red Face doesn’t wear a collar. Two other guys sit next to him at the front, but they don’t dress the part either—just suits and white shirts.

“Don’t have one.”

“Why is it ‘fast’?”

“We fast. Don’t eat. Give the money to the poor.”

“I ate.”

She smiles and squeezes my hand. “It’s okay.”

Three little girls rush the stand. Each one knows the church is true and loves her mom and dad. Two of them giggle. The last one cries. Then Stephie parades dramatically to the front. “I’m thankful for my kitty. And that Leesie’s happy again.”

She stares right at me. So does everyone else. Leesie goes crimson.

Let the flaying begin.

Stephie, pleased with the sensation she caused, finishes her speech and flounces back to her seat.

Leesie’s dad gets up right away. He speaks about praying for his family and getting answers. His soft voice pulls the congregation’s attention away from us. Her father’s words fill the room, soothing and warm. He says he loves his righteous son and strong daughters. Leesie flicks a tear out of the corner of her eye. Her face stays flushed, but she doesn’t let go of my hand.

i get emotional, too, missing my dad who loved me, righteous or not.

Leesie’s mom reaches over and pats Leesie’s shoulder. She smiles at me and winks. She’s not so bad. Carolina’s mom made her go on the pill at fourteen. She could have used a little of Leesie’s mom and some rules. Leesie should give her own a break. i study my knees and wish it wasn’t too late to give my mom a break.

People are still murmuring their final “amen” when Leesie whispers, “Let’s get out of here.”

These masochists have two more hours of meetings, but Leesie said we only have to go to this one. She’s cutting the rest with me. She gets stopped on the way out. “I’ll catch up.” i make it out of there and sit in Gram’s car trying to figure out why this church stuff is everything to Leesie.

When i see her coming, i open my door, stand so i’m halfway in, halfway out. “Hey.”

She comes around to my side. “Hey.”

We stand there stuck, until she sighs and drops her lips on mine. i pull her into the car, holding her on my lap, and return the kiss. It feels so right to have her back in my arms.

“i don’t get it.”

“Just friends is stupid.”

“Not this.” i kiss her, and she tastes better than any heaven could. “This i get.” i nod toward the ugly hall they rent. “That. i don’t get that.”

“I’m going to kill Stephie.”

“How could any of that help me? i just found out you’re all kind of egocentric about truth.”

“Didn’t you feel anything at all?”

“Embarrassment?”

“How about when my dad spoke? I saw your face.”

i have to be honest with her. “You’re right. i felt—”

“That’s the Spirit. I felt it, too. It’s so amazing when it’s strong.”

“Bereft. My parents loved me like your dad loves you. He spoke, and i felt bereft.”

Leesie strokes my cheek. “I’m sorry. The word ‘memorial’ kept floating through my head all through the meeting. Does that mean anything to you?”

“Nope.”

“You didn’t feel a tiny bit warm?”

“That wasn’t from you holding my hand?” When i try to follow that up with more heat from my lips, she gets stiff and slides off my lap.

“What did i do now?”

She flushes. “When you kiss me like that”—her voice gets small and pained—“I see you with DeeDee.” Her eyes fill up.

“Freak, Leese. i’m such a creep.”

“I really want to forgive you, but—”

“Forget her.”

“I’m trying.”

“Come back. i’ll kiss you differently.”

“I can’t.”

“Please.”

“I think it’s going to take some time.”

i hold my hand out to her. “Whatever you say.” Just don’t ditch me.

She places her hand in mine. “And we’re going to need some new rules.”

i swallow hard and whisper, “No pressure this time. i promise.”

She squeezes. “Thanks. That means a lot to me.”

“It means a lot to me.” i weave my fingers through hers. “Just let me know if you change your mind.”

She closes her eyes, thinking. “I’ve got one. No skin. No hands on my back or stomach or legs.”

“Arms?”

“That’s okay.”

“Neck?”

“Maybe, but you can never take your shirt off in my presence again.”

“You can, though. i’m cool with that.” i rub her legal arm, trying to get her to smile.

She doesn’t. i can tell she’s thinking about DeeDee again. Her eyes grow serious. “We have to ban making out, too.”

Other books

Indulgence (Taking Chances #1) by Jeanne McDonald

Beautiful Monster 2 by Bella Forrest

Book Club Killer by Mary Maxwell

I am Haunted: Living Life Through the Dead by Zak Bagans, Kelly Crigger

Cold Blood by Alex Shaw

Dragon Queen by Stephen Deas

One Night in His Custody by Fowler, Teri

Time Snatchers by Richard Ungar

These Demented Lands by Alan Warner

Only the Strongest Survive by Ian Fox