Authors: Mike Gonzalez

Tango (5 page)

2

A CITY DIVIDED

THE BIRTH OF A METROPOLIS

By 1880, Buenos Aires was ready for its new clothes and its new face. The village by the river had grown and spread. It had split into two worlds whose occasional contact was enough to create aspirations among the new immigrants in the slums and fantasies of desire among the middle classes gazing across at the transgressive and forbidden worlds down by the docks.

Argentina had changed profoundly in the previous decade. Roca's last war against the Indian populations in 1879 had not only driven them to the margins â it had also, more profoundly, made the indigenous peoples invisible to the new urban culture. The

pampas

were now enclosed as large working farms serving the burgeoning export trade. The

gauchos

who had spent their lives riding the wide grasslands were gone now â not disappeared, but transformed into shiftless wanderers in the darkened streets of the poor suburbs, the

arrabales

. In 1880, Buenos Aires was formally named the federal capital of the republic. The battle that had marked the years since formal independence in 1816 between the capital, with its European connection, and the interior provinces, whose horizons were in Latin America, was now finally resolved in the city's favour. The implications were profound. It was not just a question of where the administration of the country was located. It was a decision about how it would develop economically, and what expressions of nationhood would prevail. It was a decision about how Argentines would see themselves, and what kind of society would emerge from the fusions and encounters that were shaping the new capital.

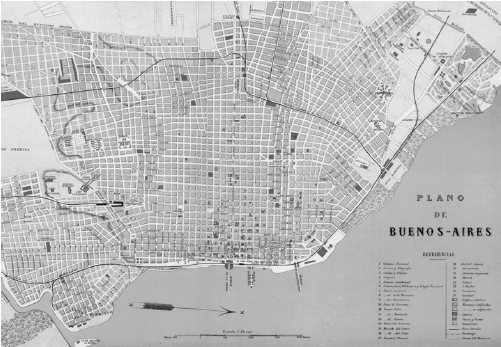

Nineteenth-century map of Buenos Aires.

The material changes were dramatic. Between 1872 and 1888 the amount of land under cultivation had risen from 600,000 hectares (about 1,500,000 acres) to 2.5 million as Argentina fast became a major producer of cereals for export. Just 20 years before, it had been importing wheat and flour! The number of sheep increased sixfold in the same period, as exports of meat and wool grew at an extraordinary rate. And in the province of Buenos Aires, surrounding the capital, some five million cattle grazed; later their numbers would also increase at speed.

1

With Buenos Aires as its capital, the Argentine economy was now confirmed as

export-led â its wool and meat and hides and cereals were all destined for Europe, and all passed through the growing port city.

The agricultural products were transported to the docks across the fast expanding rail network, mostly financed by British investors. In 1857, the country boasted just six miles of track; by 1890 that had extended to 5,800 miles. It is unlikely, of course, that any of these changes (and they were dramatic in their speed and breadth) would have been possible without the immigrant populations.

2

In the far south, the Welsh colonists enticed to Patagonia in the mid-1860s were important sheep farmers.

3

In Mendoza it was (unsurprisingly) French and Italian immigrants who drove wine production forward. But if many of them had come hoping for a piece of land to cultivate, they were mostly disappointed. They rarely managed to fulfil that dream. The bulk of immigrants made their way back to the cities, and principally to Buenos Aires, where they could find work on the docks or in construction, or in the small factories now being set up (often by wealthier immigrants) producing textiles, cigarettes and food products. Later, many would work in the slaughterhouses and meat packing plants that became increasingly central to the economy.

This newly modernizing Argentina remained a country dominated by large landowners. And they were growing very rich very quickly, not just from the goods and products they exported, but also from the lucrative land deals always associated with the laying of the railways, not to mention the earnings of lawyers and others in attendance! (Think how many Hollywood Westerns have the battle between farmers and the railway companies as a central theme.)

But the small layer of people who were growing rich in this boom period would not, by and large, be found ensconced in their rural mansions. The management of their lands would be left to stewards and foremen, while the propertied classes took themselves to the capital to enjoy the benefits brought to them by others. The capital's new status demanded a transformation that would leave

no one arriving in the city in any doubt that they were entering what would very soon be the largest city in South America â and the heart of an unprecedented economic boom.

As always, the symbolic home of civilization was Paris; a Mecca towards which every middle-class and bourgeois Argentine looked. And Paris too was in the throes of a magnificent transformation that continued the work begun under the direction of Baron Haussmann. His ideal in city planning was âlong straight streets' and wide avenues, where âthe temples of the bourgeoisie's spiritual and secular power' would find expression.

4

Walter Benjamin describes the Baron's âlove of demolition' that expropriated and swept away the old town, though his impulse came from a political need: to ensure that the barricades that had blocked the narrow streets during the short-lived workers' government of the Commune in 1871 would never appear again. Nevertheless, all the Argentine visitor saw were the Champs Ãlysées, as wide as a river, and the grand palaces and mansions around the Place de la Concorde.

That

was a proud, modern city.

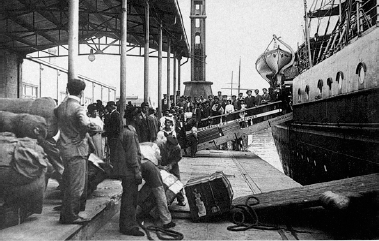

Immigrants on the gangplank.

The mayor (or

Intendente

) of Buenos Aires between 1880 and 1887 was Torcuato de Alvear, and he oversaw the emergence of the new city out of the ashes of the old. The Avenida 5 de Mayo was turned into the vast avenue it is today (though it would later be surpassed by the even wider Avenida 9 de Julio). He expanded the city's main square, the Plaza de Mayo, thousands of trees were planted and parks laid out by the French director of city parks, Carlos Thays. New public buildings and private mansions announced their civic pride. The grand new stations imitated their European counterparts, and paid homage to the critical importance of the railways. And trams, horse-drawn at first but electrified by 1900, carried the growing population from place to place.

This prosperous and optimistic urban middle class demanded its own street life, though one very different from the unlit alleys of La Boca and Nueva Pompeya. They had elegant streetlights and well-lit cafés and restaurants, as well as cabarets and theatres. From there you could not see the dimly lit slums down by the riverbank; they remained physically and socially invisible, though the middle classes were increasingly uneasy about the proximity of this population of the lower depths.

MEANWHILE . . .

While the law of 1875 had made brothels legal subject to stringent conditions, the Civil Code, published in 1871, had stressed the importance of the family, and the role of women as exemplary mothers. The paradox, or perhaps we should call it âhypocrisy', persisted; the Code's condition of existence was the marginalization of that other obscure world of the poor. The obsession with âinfection', the endless public debates over venereal disease, the fascination with the forbidden, all testify to the contradiction. And for a decade or two, the two worlds were successfully kept apart.

The poor areas of the city supplied a working class for the new factories, most of them small plants at first, and for the larger factories that would spread through the Barracas district, later (and still) called Avellaneda. As the city was beautified and transformed, the prostitutes â or at least the majority of the street and café workers â were expelled from the upper-class districts. The elegant brothels catering to the upper middle class, like La Casa de Laura, however, were never closed. And there were growing numbers of women seeking work in the brothels. The transformation of the countryside, and the shortage of rural employment, brought a new generation of women to the shadowy demi-monde of cafés and

academias

.

Yo soy la Morocha

La más agraciada

,

La más renombrada

De esta población

.

Soy la que al paisano

Muy de madrugada

Brinda un cimarrón. . .

Soy la morocha argentina

,

La que no siente pesares

,

Y alegre pasa la vida

Con sus cantares

.

Soy la gentil compañera

Del noble gaucho porteño

La que conserva la vida

Para su dueño

.

I am the Brown Girl / the best endowed / the most famous woman / in this town / I'm the one the countryman / early in the morning / makes a present of a pony to . . .

I'm the Argentine brown girl / who feels no sorrow / and cheerfully spends her life / singing her songs

.

I'm the charming companion / to the noble gaucho of these plains / the woman who protects the life / of her master

.

(âLa Morocha', The Brown Girl â Ãngel Villoldo, 1905)

The majority of

registered

prostitutes were foreign women, for whom registration offered some minimal degree of protection, even if it involved paying off the police on a regular basis. And the disproportion of men to women (170 men per 100 women) guaranteed a growing clientele, as immigration picked up again through the 1880s after a brief lull at the end of the previous decade.

The 1880s and 1890s brought other opportunities for employment for women outside the home, as they found work in the factories producing food or clothing, or sewing the sacks for the growing quantities of cereals that the country exported. The bulk of those who worked, however, still found positions in domestic service. In the 1890s, some would find work in the elegant department stores opening their doors on the Calle Florida â the most famous of which, Harrod's, was opened later, in 1914. By 1895, 20 per cent of the workforce were women. Some of them, of course, would have supplemented their wage labour with extra hours as waitresses downtown.

The men, waiting in the queues outside the brothels for their opportunity to dance, might have found the street a freer place to be than the overcrowded slums they returned to after a day's work on the construction of the new city.

Tango remained the dance of the lower depths; the expression of the strange merger of people and communities that was the melting pot where the new Argentina was being formed. Since the women were relatively few, and their time for dancing restricted, the men would practise in the street or in the

academias

. The musicians who played for them were workers like themselves who often played through the night before leaving for work early the next morning. Their trios, most commonly comprising the flute, violin and harp (the guitar, the clarinet and the emblematic bandoneon came later), played the fast, improvised rhythms of the new dance, associated in style and location with the underworld of pimps and prostitutes. It was still marked by its origins in the black population, from whom came the elaborate twisting and jerking of the body which so appalled the respectable ladies of the city.

An early twentieth-century tango quartet. |

|