Ted and Ann - The Mystery of a Missing Child and Her Neighbor Ted Bundy (7 page)

Read Ted and Ann - The Mystery of a Missing Child and Her Neighbor Ted Bundy Online

Authors: Rebecca Morris

The boyfriends may be dead, but they had money and good taste when alive.

While the titles of the magazine articles seemed as benign as a

Perry Mason

episode (

The Clue of the Discarded Nylons,

and

The Killer Liked Apple Pie

appear in those issues), Ted liked the magazines because some of them were graphic inside, with real crime scene photos of dead and sexually assaulted bodies (later, he called the magazines “very potent material”). Some of the titles of the articles could have described Ted’s crimes, years later:

Bludgeoned Brunette in Butternut Creek,

and

Case of the Strangled Coed,

were featured in

True Detective

in 1966.

Ted could have followed the careers of Tacoma’s two most-famous crime fighters, detectives Tony Zatkovich and Ted Strand, colorfully described in articles titled

Rendezvous With A Corpse

and

Let Me Lead You To His Grave

in magazines promising “authentic stories of crime detection.” In April 1966, Ted could have read in

Master Detective

about a crime close to home. The headline to the story was: An Appeal to Master Detective Readers - CAN YOU HELP FIND ANNE [

sic

] MARIE BURR?

Ted would be a police junkie the rest of his life (extremely common for serial killers). Beginning with the magazines and books on crime he could find at the library, he studied police procedures and how people got away with murder. It may have seemed to his parents that it was just another hobby—if they even knew of his interest in police work and murder. All Louise remembered was finding a copy of

Playboy

under his bed once or twice during his teenage years. (Many years later, after Ted’s death, the FBI noted how he sometimes used his victims to re-enact scenarios on the covers of detective magazines.)

It wasn’t until near the end of his life that Ted would describe the beginnings of what he called—with gross understatement—his “trouble” or his “problem.” Referring to his teenage interest in peeping, Ted told journalist Stephen Michaud, “Again, this is something that a lot of young boys would do and without intending any harm, and that was basically where I was at the time. But I see how it later formed the basis for the so-called entity, that part of me that began to visualize and fantasize more violent things…”

His fascination with sex and murder coincided with other changes in Ted. He didn’t understand social interactions. “I didn’t know what made things tick,” he told Michaud. “I didn’t know what made people want to be friends. I didn’t know what made people attractive to one another. I didn’t know what underlay social interactions.” He had trouble completing things and so had a spotty and erratic college career and job history. He marveled at the ease with which his four half-siblings fit in. In high school he felt out of touch with his peers, including boys he had grown up with. He described himself as “stuck,” and told Michaud, “In my early schooling, it seemed like there was no problem in learning what the appropriate social behaviors were. It just seemed like I hit a wall in high school.” His explanation of those years is contradictory and secretive. In other words, pure Ted Bundy.

“It was not so much that there were significant events (in my boyhood), but the lack of things that took place was significant,” Ted continued. “The omission of important developments. I felt that I had developed intellectually but not socially. In junior high, everything was fine. Even went to some parties. Nothing that I can recall happened that summer before my sophomore year to stunt me or otherwise hinder my progress. Emotionally and socially, something stunted my progress in high school. Not that I ever got into trouble. Or wanted to do anything wrong.”

His friends complained that he would make plans with them, then not show up. Or he would come up behind them suddenly to scare them (he liked to strangle his victims from the rear, too). And Ted began prowling.

Ted would say of his teenage years, “I loved the darkness, the darkness would excite me, it was really sort of my ally, because I could creep around in the darkness.” And, according to Sandi Holt, Ted was drinking heavily in high school; for the rest of his life alcohol would be a depressant that would prompt his spiraling moods and loosen his inhibitions so he could kill.

Eventually, Ted began thinking and speaking of his behavior in a detached way. He hinted that he began murdering young. Maybe that’s what he meant when he said that “something happened” when he was a teenager. He could mention his crimes, but only in the third person. “The first victim of this other person could have been an 8- or 9-year-old girl,” he told an expert on serial killers. It was a round-about way of confessing without confessing, one more way to titillate and manipulate the police, yet remain in charge.

The Bundy’s must have read or heard about the little girl missing in their former neighborhood. The news coverage of the search for Ann Burr was on the front page of the Tacoma newspaper every day, and was covered by the two Seattle newspapers, as well as local radio and television. Sandi Holt heard the news on the radio and burst into tears, telling her mother that she knew the little girl who had vanished.

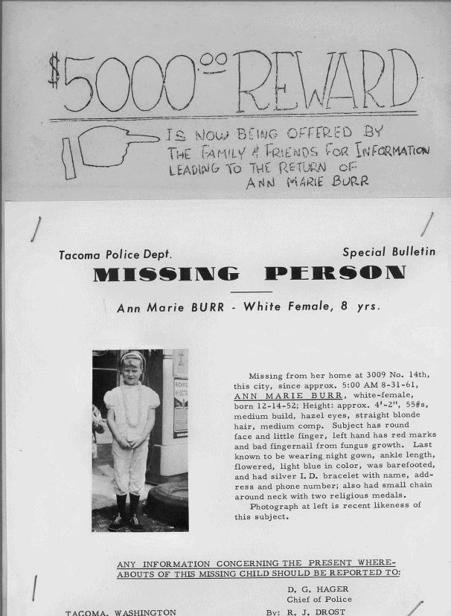

Even if Louise was house-bound by her fifth pregnancy, she had to have known that just two blocks from where she and Teddy had lived with her uncle, a child had likely been abducted. She had children about the same age. Bev had put up missing posters at grocery stores all over town. The compelling posters, with big lettering and the haunting photo of Ann, were everywhere. Ted was a paperboy for one of the Seattle papers. Did Louise empathize with the mother of the missing girl? Ted’s friend, Jerry Bullat, remembers his own mother being distraught about Ann’s disappearance. So were the parents of the other children who played with Ann and parents with children attending Grant Elementary. Sandi Holt’s mother immediately kept a closer rein on Sandy, and Doug was ordered to walk her to Geiger Elementary when the new school year began.

Over the years, Bev Burr and Louise Bundy would meet by accident. They didn’t speak, but they had a lot in common. They were petite, they kept their hair style simple and wore no makeup, and they were intelligent. They were married to working-class men, and both had five children. Each would lose her oldest child, the one with the most promise, in a horrific way. And at the most stressful times in their lives, they coped in the same way: they offered guests apple pie.

In 1961, Ted was getting ready to begin ninth grade at Hunt Junior High. As Tacoma police questioned hundreds of teenagers and men (two of their prime suspects being just 13 and 15 years old) about the disappearance of Ann Burr, there were thousands more they didn’t know. The name Ted Bundy didn’t come to their attention because he didn’t live in the north end of the city, and Ted’s family was Methodist; the Burrs and most of their friends and neighbors—all potential suspects—attended St. Patrick’s. Although he roamed and peeped, Ted wouldn’t be known to Tacoma police until a few years later, when he reportedly was picked up on suspicion of auto theft and burglary. Those records were reportedly expunged while he was still a juvenile.

In the summer of 1961, Ted was 14 years old; he would turn 15 in November. He told Dr. Dorothy Otnow Lewis that when he was …“twelve, fourteen, fifteen…in the summer…something happened, something, I’m not sure what it was. ..I would fantasize about coming up to some girl sunbathing in the woods, or something innocuous like that….I was beginning to get involved in what they would call, developed a preference for what they call, autoerotic sexual activity,” he told her. “A portion of my personality was not fully…it began to emerge…by the time I realized how powerful it was, I was in big trouble…”

Ted’s favorite subject was Ted. He loved to talk. A state Republican party leader who got to know Ted said he had “the gift of gab” and “oozed sincerity.” One advantage to being on death row for years is that many sought him out, and he could expound on his theories, including that of killers who begin young. “Perhaps the only firm trend I ever ran across in the study of abnormal behavior,” Ted told a journalist, “was that the younger that a person…that he or she was when they manifested abnormal behavior or thought pattern…the more likely it was that there was going to be a condition that would be lasting. And, uh, permanent. A chronic disorder.”

Later, when the police, the media, and the Burrs wondered if Ted could have begun his killing with one small girl, a girl who didn’t fit the image of the college coeds he killed (although the last girl he killed was just 12, and there were a couple of 14 year olds, too), a young girl who wasn’t in college and didn’t have long hair parted in the middle, Louise Bundy went on the defensive. She told the

Tacoma News Tribune,

“I resent the fact that everybody in Tacoma thinks just because he lived in Tacoma he did that one too, way back when he was 14. I’m sure he didn’t. We were such a close family…he didn’t have anything against little girls.”

The missing poster created August 31, 1961.

Beverly Burr’s father, Roy Leach,

on the porch of his Tacoma grocery store.

Bev’s sixth grade class at Central Elementary School in 1939. Bev is third from left in the front row. Her friend Haruye Kawano is second from right in the front row.

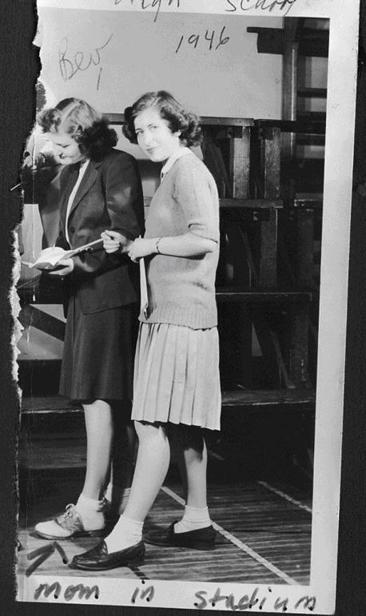

Bev, at left, as yearbook editor,

Stadium High School, 1945-46.