Ted & Me (6 page)

Authors: Dan Gutman

Where Am I?

I

OPENED MY EYES, BUT THERE WASN'T MUCH TO SEE

. I

T WAS

dark out. I was standing on a street corner, and the streetlights were dimmer than I remembered them. There were tall buildings around, and cars parked on both sides of a wide avenue. It was a big cityâBoston, I figured. So far, so good. At least I wasn't in another plane.

I looked up to read the street sign. The wide street was called Market, and the smaller cross street was 8th.

It was warm out, but not hot. It felt like the end of the summer when it's just starting to get chilly at night in anticipation of fall. Good. If it was really cold, I would worry because that would mean I might have arrived after December 7âthe date Pearl Harbor was attacked.

One of the first things I noticed was the cars on

the street. It wasn't that they were

old

. I knew that cars from the 1940s were big and rounded, and a lot of them had whitewall tires. No, the surprising thing about the cars was that they were

filthy

. Back home there's an antique car show every year, and the cars are always shiny and perfect. So I naturally assumed that cars in the old days looked like that too. But now that I was seeing them with my own eyes, I noticed that a lot of them were dirty and dented. They hadn't been restored.

Not many people were out on the street.

It must be pretty late at night,

I figured. I certainly didn't see Ted Williams anywhere.

But it was okay. That was the way it always workedâI would land in the general vicinity of the player on the card. Then I would have to find him. Time travel is not an exact science.

Maybe I was a few blocks from Fenway Park, I guessed. I used the old eenie, meenie, miney, moe system to pick a direction and started walking down Market Street. I kept turning around as I walked to make sure nobody was following me. More than anything else, I didn't want to get mugged. If somebody took my pack of new baseball cards, I would never be able to get back to my own time. I patted my pocket to make sure I still had it.

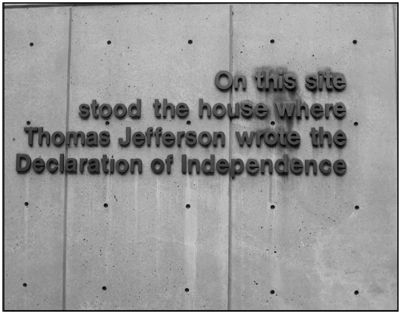

The first cross street I came to was 7th Street, so I made a mental note that I was walking downtown. On the corner was a little brick house with a sign in front of it. I had to get up close to it to read the wordsâ¦

Huh! I didn't know the Declaration of Independence had been written in Boston.

After walking a couple of blocks, I was beginning to get discouraged. Maybe I was walking in the wrong direction. What if Ted Williams was

uptown

somewhere? I decided to ask for directions.

A man wearing a hat was walking down the sidewalk toward me.

“Excuse me,” I asked him, “which way to Fenway Park?”

The guy gave me a weird look and walked by without responding. He probably thought I was going to hit him up for money.

A man and a woman were coming toward me arm in arm. The guy also was wearing a hat. It occurred to me that

all

the men were wearing hats. I guess men wore hats in those days, even in the summer.

“Am I heading toward Fenway Park?” I asked the couple.

The woman giggled and pulled her man away from me as if I had a contagious disease.

“What are you, a wise guy?” the man said as they hurried past me, laughing.

Maybe this

wasn't

Boston, it occurred to me.

I spotted a garbage can on the next corner and rushed over there. Just as I'd hoped, there was a newspaper in it. I grabbed it.

Philadelphia?

Of

course!

The Declaration of Independence wasn't written in Boston. It was written in Philadelphia. We learned that in school. No wonder those people looked at me strangely when I'd asked them how to get to Fenway Park.

I sat down on a bench between 6th and 5th Streets to think things over. What was I doing in

Philadelphia? Ted Williams played for the Red Sox in the American League. The Phillies were in the National League. I knew that back in the old days, there was no interleague play. The Phillies and Red Sox would never play each other. Something must have gone wrong. Again.

I cursed my bad luck. How come I never land where I

want

to land? The last time, when I went to see Roberto Clemente, I landed in New York even though Clemente was in Cincinnati. Now I had landed in Philly even though Williams was in Boston. Just

once

I wish it was easy.

It looked like I would have to take a train to Boston. I didn't know where the train station was or if the trains ran at night. And I didn't even think to bring money with me. This was not looking good.

I scanned the front page of the newspaper. I always liked newspapers. You can learn a lot of stuff from them. A lot of people, I know, use electronic readers now. But I like the feeling of paper.

A nearby streetlamp was bright enough so I could read. I squinted to see the date at the top of the front page: September 27, 1941.

Well, at least my timing was right. It was about ten weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The front page was filled with stories about the war raging in Europe. An article said that Nazi U-boats were terrorizing the North Atlantic Ocean. The German air force, the Luftwaffe, was bombing England. Germany's biggest battleship, the

Bismarck

, had been sunk on May 27. Hitler invaded the Soviet Union on June 22, and the Nazis had just reached Leningrad.

Nothing about Japan. At least according to the newspaper, Japan wasn't even considered a threat. No wonder the attack on Pearl Harbor came as such a surprise.

I turned to the sports section. The Brooklyn Dodgers had won the National League pennant, and the Yankees had won in the American League. The World Series was scheduled to begin in three days at Yankee Stadium. The second page of the sports section had an article about Ted Williams.

September 28âthe next dayâwould be the last day of baseball season. Ted's batting average stood at .39955âjust below the magical .400 mark. It would all come down to a doubleheader the next day againstâ¦THE PHILADELPHIA ATHLETICS.

That's right! Back in the old days, Philadelphia had a team in the American League called the Athletics, or the A's. The Red Sox were going to play the Philadelphia Athletics on the last day of the season. That meant that Ted Williams was in Philadelphia!

So

that's

why I landed here. I didn't have to take a train to Boston. Ted Williams was somewhere near me. I just had to track him down.

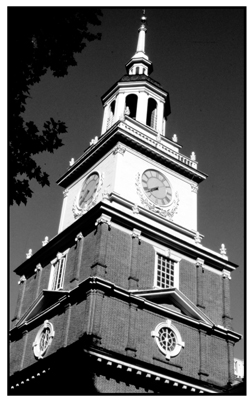

He was probably staying in a hotel nearby, I figured. I stuffed the newspaper back into the garbage can and looked around. There was a grassy field behind me and a grand-looking building at the other end, about a block away. It could be a hotel. Somehow, it looked familiar. I walked toward it.

I remembered the building. We had learned about it in school.

As I got closer to the building, I remembered that I had seen it before. Twice, in fact. It was in my Social Studies textbook and also in that movie

National Treasure

. This wasn't any hotel. It was Independence Hall! Thomas Jefferson wrote the Declaration of Independence a few blocks away from this spot, and then he must have walked down Market Street to this building, where the declaration was signed. I remembered that the United States Constitution was also written in this very same building. I had a test on all this stuff at school just a few weeks earlier.

Finding Ted Williams could wait.

In the twenty-first century, I would bet, you can't get close to an historic building like this one. They probably have barricades all around it, and armed guards. But on this night, in 1941, there was nobody around. I could walk right up to the building and touch it.

I stood on my tiptoes to look inside the window. There were no lights on inside Independence Hall; but from the streetlights and the light of the moon, I could see a faint outline of something that was familiar to me.

It was the Liberty Bell.

There it was. I could even see the crack. I couldn't make out the words written on it, but I knew what they were because we had to memorize them for a test: “Proclaim LIBERTY throughout all the Land unto all the inhabitants thereof.”

I stood there for a few minutes marveling at the

fact that I was standing with my nose against the window of the building in which our country was born. I was staring at the symbol of America, and the most famous bell in the world. I was so caught up in the moment that I didn't notice the guy standing next to me.

“It's a beautiful thing, huh?” he said.

I glanced at him. He was a tall guy, maybe 6 feet 3 or so, and thin. He had long legs and a long neck, which made him slightly goofy looking. I recognized the face.

“You're not⦔

“The name is Williams,” he said, sticking out his hand, “Ted Williams.”

The Heebie-Jeebies

I

JUST STARED AT

T

ED

W

ILLIAMS'S FACE FOR THE LONGEST

time. He probably thought I was crazy.

It was obviously the same guy I had met the first time, in the plane. He had the same curly black hair and bushy eyebrows. But he was so much younger now. Twelve years, I quickly calculated. In 1941, Ted Williams was just ten years older than me.

The biggest difference was that he was so skinny. I recalled his nicknames: the Splendid Splinter, the Stringbean Slugger, and Toothpick Ted. It didn't look like the man standing next to me was capable of hitting one home run, much less 521 of them. He must have had a perfect swing.

“You look so different,” I blurted out.

Ted looked at me oddly.

“Different from what?” he asked. “Did I meet you before?”

“In the plane⦔

As soon as the words left my mouth, I realized it was a stupid thing to say. For all I knew, Ted Williams hadn't even had his first plane ride yet.

“What plane?” he asked. “Are you nuts, Junior?”

I could have slapped myself.

It's 1941, idiot! When we crash-landed in South Korea, it was 1953. He's not going to know about that. It didn't happen yet.

“I'm sorry,” I said, flustered. “I'm a little nervous. I never met anybody famous before.”

“Forget it,” he replied. “What are you doing out on the streets this late at night? Are you lost?”

He had that same loud voice but seemed a little more soft-spoken than he would become in 1953. He wasn't cursing as much either.

“No,” I said. “I'm just outâ¦walking around.”

“Do your mom and dad know you're here?” he asked, sounding genuinely concerned.

“Well, yeah,” I said. “I mean no. Not exactly.”

“Where are they?”

“In Kentucky,” I told him. “Louisville.”

“Louisville?” Ted asked. “Did you run away from home? You're gonna get yourself killed, Junior! There are all kinds of nuts roaming the streets at this hour, y'know. I'm sending you home. What's your name?”

“No, don't send me home!” I exclaimed. “Look, my name is Joe Stoshack. I'm not lost. I didn't run away from home. I'm fine. It's a long story.”

And this wasn't the time to tell it. I knew that if I told Ted Williams I came from the future and

that I can travel through time with baseball cards, he would be

sure

I was crazy. He might take me to a mental hospital or something. No, I would have to win his trust before telling him the truth about why I was there. I would wait until the time was right.

Famous people, I'd heard, usually care about one thing more than anything else: themselves. I thought it would be best to change the subjectâto Ted.

“What are

you

doing out here so late?” I asked him. “Don't you have a game tomorrow?”

“Two,” he replied. “A doubleheader. I like to walk at night. It helps me think. You wanna keep me company for a while, Junior?”

“Sure.”

He pulled a shapeless, rumpled hat out of his pocket and put it on.

“I don't want to be recognized by anybody else,” he said.

I glanced at a sign on the corner and saw that we were on Chestnut Street. Ted seemed to know where he was heading. I followed. He walked quickly with his head down, as if he was looking for change on the sidewalk.

I noticed for the first time that he had a pink rubber ball in his right hand, and he was squeezing it.

“What's the ball for?” I asked.

“It makes my hands strong,” he replied.

We crossed 5th Street. A park was on the right, and there was a homeless man wrapped in a blanket asleep on a park bench. There was a shopping cart

next to him with some bags in it. Ted stopped for a moment in front of the guy.

“Look at that,” he said disgustedly, “a block from the Liberty Bell. How could a country as rich as America have people living like that? It's a sin.”

Ted pulled a bill out of his wallet and slipped it into the homeless man's bag. The guy never woke up.

“You said walking helps you think,” I said to Ted as we crossed 4th Street. “So what are you thinking about?”

“I got the heebie-jeebies,” Ted said.

“Huh?” I had no idea what that meant. It sounded like a disease.

“You probably know about the whole .400 thing,” Ted said.

“Yeah,” I said, “your batting average is .399, and tomorrow's the last day of the season.”

“It's .3995535, actually,” he said. “If I stopped playing right now, it would be rounded up to an even .400. We're not fighting for the pennant or anything. The games tomorrow don't matter. So Cronin said I could sit out the doubleheader if I want to. It would go into the record books as .400.”

I remembered the name Joe Cronin. I had read about him in my baseball books. He was a Hall of Famer who became the manager of the Red Sox after his career was over.

“So that's why you have the heebie-jeebies?” I asked. “What's the problem?”

“The problem is, that's not the way The Kid does

things,” he replied. “You don't become great by sitting on a bench.”

The Kid. That was another one of his nicknames, I remembered, and he used it himself.

I wondered if the athletes of the twenty-first century would feel the same way as Ted. If any of today's players hit .400 for a season, it would be

huge

. The guy would be all over the news. He'd get his picture on a Wheaties box. He would make millions of dollars doing TV commercials. And if he was hitting .3995535 going into the last day of the season, I would bet he would sit out that last game rather than risk dipping below an official .400 batting average. His agent would insist on it. The players in 1941 didn't even have agents. They hardly made any money, anyway.

But as we turned right on 3rd Street around the perimeter of the park, it was obvious that Ted was struggling with his decision about the next day.

“It's gonna be tough,” he told me. “Unless I have a great day, I blow it. One of the other guys on the team figured it out for me. If I go 1 for 3, or 2 for 6, my average doesn't get rounded up to .400. I finish up at .399.”

Ted went on to tell me everything he would be up against the next day. The game would be at Shibe Park, which was a terrible field for hitters in September. Shadows from the stands made it so the pitcher was in the sun while home plate was in shadow. So the hitter didn't get a good view of the ball. And the

pitcher's mound was 20 inches high, one of the highest in baseball.

Furthermore, Ted told me, he was not a fast runner, so he hardly ever got any cheap infield hits. He had to hit the ball

hard

to get it past the infield for every hit and hope he didn't hit it right

at

an infielder.

Finally, he told me that over the last ten days of the season, his average had been dropping almost a point a day. Since September 10th, he had only been averaging .270.

I had to be very careful here, I realized. He had given me a lot of reasons why he should sit out the doubleheader but only one reason why he should play: his pride.

I knew that Ted Williams was going to finish the season with a .406 batting average, and I knew what he was going to do in each at-bat. It was in the history books.

But I remembered what my mother had said: What if I stepped on a twig and changed history for the

worse

? What if I did something, or said something, that made Ted decide

not

to play the last day of the season? It would change everything. He would finish the season batting .3995535. That's still an incredible accomplishment. But it's not an honest .400. And it would be my fault.

I couldn't put myself in Ted Williams's shoes, of course, but I had an idea of what he was going through. There had been nights I would lie in bed with my eyes open trying to decide what I should

do or what choice I should make. I remember when my next-door neighbor Miss Young paid me to throw out all the junk in her attic and I'd found a valuable Honus Wagner baseball card in there. I really struggled over whether I should keep the card for myself or give it back to Miss Young.

“What do you think you're gonna do?” I asked Ted as we turned right at the next corner, which was Walnut Street.

“I don't know,” he said. “It's been a long season, and I'm tired. Maybe I'll sit it out tomorrow.”

Uh-oh. This wasn't good. Maybe I had

already

said something that changed his mind. Maybe I had

already

changed history. I had to do something.

We were walking back uptown now. As we crossed 4th Street, I decided to tell him what I knew: if he played the next day, he would not only hit .400, but he would even

beat

.400. If he thought I was crazy and called the cops, well, that was the chance I had to take.

“Mr. Williams,” I finally said. “I really think you should play tomorrow.”

“Why, Junior?” he asked.

I took a deep breath.

“You're gonna go 6 for 8 in the doubleheader,” I told him. “You're gonna raise your average to .406.”

Ted stopped walking.

“You sound pretty confident for a kid,” he told me. “How come you're so sure of yourself?”

“I just have a feeling, that's all,” I replied.

“Sometimes I feel like I can see the future. It's sort of like a sixth sense.”

We crossed 5th Street and then 6th. Ted wasn't talking anymore. He was deep in thought.

The park we had been walking around ended at 6th Street, and we continued walking uptown on Walnut. At 9th Street Ted turned right, and after two short blocks we were on Chestnut Street again. We had made a big circle around the park. Ted turned to me.

“I'll sleep on it,” he said simply.

“Okay.”

He had stopped in front of a big building with a fancy front entrance. A sign above said

BEN FRANKLIN HOTEL.

“Where are you going to sleep tonight, Junior?” Ted asked me.

“I don't know.”

“You can bunk with me,” he said. “I have a feeling you might be my good-luck charm.”

We went inside and rode the elevator up to his room. Ted took a blanket out of the closet and improvised a bed for me on the floor. He put on a pair of pajamas, then got down on the floor and did a bunch of fingertip push-ups. When he stopped, he told me he was trying to make his muscles as big as his teammate Jimmy Foxx's.

I don't remember what happened after that because I fell asleep right away.

Â

Sometime in the middle of the night I woke up. There was a noise. I looked around and saw Ted sitting in his pajamas at the little desk next to the bed. He was holding a bottle of alcohol.

A lot of ballplayers had problems with booze, I knew. Especially back in the old days. But I had never heard anything about Ted Williams being a drinker. I could hardly believe he would be hitting the bottle before this game, of all games.

“You're drinking

booze

?” I asked, rubbing my eyes.

“Booze?” he said, and then he looked at the bottle and laughed. “I never touch the stuff. I'm not drinkin' this !@#$%! I'm cleanin' my bat with it!”

I sat up and saw that he had a rag in his hand. He poured some of the alcohol on the rag and then wiped his bat with it. He told me he did it every night, because a bat will pick up dirt and moisture during a game, which can add an extra half ounce.

“Besides,” he added, “I can't sleep.”

After he finished cleaning the bat, he took out a scale and weighed it to make sure it was perfect.

It was hard to imagine what he was going through. To me, 400 was just a number. 400â¦406â¦399â¦who cares? When you get down to it, it doesn't really mean anything.

“How important is it for you to hit .400?” I asked him.

“I never wanted anything more,” he told me. “All I want out of life is that when I walk down the street

folks will say, âThere goes the greatest hitter who ever lived.'”

At some point I fell back asleep to the gentle background music of Ted Williams grinding his teeth in the dark.