Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories (16 page)

Read Ten Days in a Mad-House and Other Stories Online

Authors: Nellie Bly

Tags: #Psychology, #Medical, #General, #Psychiatry, #Mental Illness, #People With Disabilities, #Hospital Administration & Care, #Biography & Autobiography, #Editors; Journalists; Publishers, #Social Science

of the bureau for a month,” he urged, but the visitor began to get

Ten Days in a Mad-House

more nervous and to make his way to the door. I thought he was

frightened because it was an agency, and it amused me to hear how

earnestly he pleaded that really he dare not employ a girl without his

wife’s consent.

After the escape of this visitor we all resumed our former positions

and waited for another visitor. It came in the shape of a red-haired

Irish girl.

“Well, you are back again?” was the greeting given her.

“Yes. That woman was horrible. She and her husband fought all the

time, and the cook carried tales to the mistress. Sure and I wouldn’t

live at such a place. A splendid laundress, with a good ‘karacter,’

don’t need to stay in such places, I told them. The lady of the house

made me wash every other day; then she wanted me to be dressed

like a lady, sure, and wear a cap while I was at work. Sure and it’s no

good laundress who can be dressed up while at work, so I left her.”

The storm had scarcely passed when another girl with fiery locks

entered. She had a good face and a bright one, and I watched her

closely.

“So you are back, too. You are troublesome,” said the agent. Her

eyes flashed as she replied:

“Oh, I’m troublesome, am I? Well, you can take a poor girl’s money,

anyway, and then you tell her she’s troublesome. It wasn’t

troublesome when you took my money; and where is the position? I

have walked all over the city, wearing out my shoes and spending

my money in car-fare. Now, is this how you treat poor girls?”

“I did not mean anything by saying you were troublesome. That was

only my fun,” the agent tried to explain; and after awhile the girl

quieted down.

Another girl came and was told that as she had not made her

appearance the day previous she could not expect to obtain a

Ten Days in a Mad-House

situation. He refused to send her word if there was any chance. Then

a messenger boy called and said that Mrs. Vanderpool, of No. 36

West Thirty-ninth Street, wanted the girl advertised in the morning

paper. Irish girl No. 1 was sent, and she returned, after several

hours’ absence, to say that Mrs. Vanderpool said, when she learned

where the girl came from, that she knew all about agencies and their

schemes, and she did not propose to have a girl from them. The girl

buttoned Mrs. Vanderpool’s shoes, and returned to the agency to

take her post of waiting.

I succeeded at last in drawing one of the girls, Winifred Friel, into

conversation. She said she had been waiting for several days, and

that she had no chance of a place yet. The agency had a place out of

town to which they tried to force girls who declared they would not

leave the city. Quite strange they never offered the place to girls who

said they would work anywhere. Winifred Friel wanted it, but they

would not allow her to go, yet they tried to insist on me accepting it.

“Well, now, if you won’t take that I would like to see you get a place

this winter,” he said, angrily, when he found that I would not go out

of the city.

“Why, you promised that you would find me a situation in the city.”

“That’s no difference; if you won’t take what I offer you can do

without,” he said indifferently.

“Then give me my money,” I said.

“No, you can’t have your money. That goes into the bureau.” I urged

and insisted, to no avail, and so I left the agency, to return no more.

My second day I decided to apply to another agency, so I went to

Mrs. L. Seely’s, No. 68 Twenty-second Street. I paid my dollar fee

and was taken to the third story and put in a small room which was

packed as close with women as sardines in a box. After edging my

way in I was unable to move, so packed were we. A woman came

up, and, calling me “that tall girl,” told me roughly as I was new it

Ten Days in a Mad-House

was useless for me to wait there. Some of the girls said Mrs. Seely

was always cross to them, and that I should not mind it. How

horribly stifling those rooms were! There were fifty-two in the room

with me, and the two other rooms I could look into were equally

crowded, while groups stood on the stairs and in the hallway. It was

a novel insight I got of life. Some girls laughed, others were sad,

some slept, some ate, and others read, while all sat from morning till

night waiting a chance to earn a living. They are long waits too. One

girl had been there two months, others for days and weeks. It was

good to see the glad look when called out to see a lady, and sad to

see them return saying that they did not suit because they wore

bangs, or their hair in the wrong style, or that they looked bilious, or

that they were too tall, too short, too heavy, or too slender. One poor

woman could not obtain a place because she wore mourning, and so

the objections ran.

I got no chance the entire day, and I decided that I could not endure

a second day in that human pack for two situations, so framing some

sort of excuse I left the place, and gave up trying to be a servant.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Nellie Bly as a White Slave.

HER EXPERIENCE IN THE ROLE OF A NEW YORK SHOP-GIRL

MAKING PAPER BOXES

.

ERY early the other morning I started out, not

with the pleasure-seekers, but with those who

toil the day long that they may live. Everybody

was rushing–girls of all ages and appearances

and hurrying men–and I went along, as one of

the throng. I had often wondered at the tales of

poor pay and cruel treatment that working girls

tell. There was one way of getting at the truth, and I determined to

try it. It was becoming myself a paper box factory girl. Accordingly, I

started out in search of work without experience, reference, or aught

to aid me.

It was a tiresome search, to say the least. Had my living depended on

it, it would have been discouraging, almost maddening. I went to a

great number of factories in and around Bleecker and Grand streets

and Sixth Avenue, where the workers number up into the hundreds.

“Do you know how to do the work?” was the question asked by

every one. When I replied that I did not, they gave me no further

attention.

“I am willing to work for nothing until I learn,” I urged.

“Work for nothing! Why, if you paid us for coming we wouldn’t

have you in our way,” said one.

“We don’t run an establishment to teach women trades,” said

another, in answer to my plea for work.

“Well, as they are not born with the knowledge, how do they ever

learn?” I asked.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“The girls always have some friend who wants to learn. If she wishes

to lose time and money by teaching her, we don’t object, for we get

the work the beginner does for nothing.”

By no persuasion could I obtain an entree into the larger factories, so

I concluded at last to try a smaller one at No. 196 Elm Street. Quite

unlike the unkind, brusque men I had met at other factories, the man

here was very polite. He said: “If you have never done the work, I

don’t think you will like it. It is dirty work and a girl has to spend

years at it before she can make much money. Our beginners are girls

about sixteen years old, and they do not get paid for two weeks after

they come here.”

“What can they make afterward?”

“We sometimes start them at week work–$1.50 a week. When they

become competent they go on piecework–that is, they are paid by the

hundred.”

“How much do they earn then?”

“A good worker will earn from $5 to $9 a week.”

Ten Days in a Mad-House

“Have you many girls here?”

“We have about sixty in the building and a number who take work

home. I have only been in this business for a few months, but if you

think you would like to try it, I shall speak to my partner. He has

had some of his girls for eleven years. Sit down until I find him.”

He left the office, and I soon heard him talking outside about me,

and rather urging that I be given a chance. He soon returned, and

with him a small man who spoke with a German accent. He stood by

me without speaking, so I repeated by request. “Well, give your

name to the gentleman at the desk, and come down on Monday

morning, and we will see what we can do for you.”

And so it was that I started out early in the morning. I had put on a

calico dress to work in and to suit my chosen trade. In a nice little bundle, covered with brown paper with a grease-spot on the center

of it, was my lunch. I had an idea that every working girl carried a

lunch, and I was trying to give out the impression that I was quite

used to this thing. Indeed, I considered the lunch a telling stroke of

thoughtfulness in my new

role

, and eyed with some pride, in which

was mixed a little dismay, the grease-spot, which was gradually

growing in size.

Early as it was I found all the girls there and at work. I went through

a small wagon-yard, the only entrance to the office. After making my

excuses to the gentleman at the desk, he called to a pretty little girl,

who had her apron full of pasteboard, and said:

“Take this lady up to Norah.”

“Is she to work on boxes or cornucopias?” asked the girl.

“Tell Norah to put her on boxes.”

Following my little guide, I climbed the narrowest, darkest, and

most perpendicular stair it has ever been my misfortune to see. On

and on we went, through small rooms, filled with working girls, to

Ten Days in a Mad-House

the top floor–fourth or fifth story, I have forgotten which. Any way, I

was breathless when I got there.

“Norah, here is a lady you are to put on boxes,” called out my pretty

little guide.

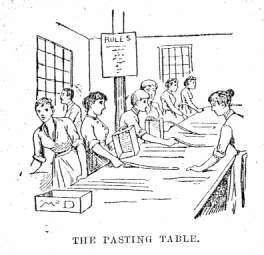

All the girls that surrounded the long tables turned from their work

and looked at me curiously. The auburn-haired girl addressed as

Norah raised her eyes from the box she was making, and replied:

“See if the hatchway is down, and show her where to put her

clothes.”

Then the forewoman ordered one of the girls to “get the lady a

stool,” and sat down before a long table, on which was piled a lot of

pasteboard squares, labeled in the center. Norah spread some long

slips of paper on the table; then taking up a scrub-brush, she dipped

it into a bucket of paste and then rubbed it over the paper. Next she

took one of the squares of pasteboard and, running her thumb deftly

along, turned up the edges. This done, she took one of the slips of

paper and put it quickly and neatly over the corner, binding them

together and holding them in place. She quickly cut the paper off at

the edge with her thumb-nail and swung the thing around and did

the next corner. This I soon found made a box lid. It looked and was

very easy, and in a few moments I was able to make one.

I did not find the work difficult to learn, but rather disagreeable. The

room was not ventilated, and the paste and glue were very offensive.

The piles of boxes made conversation impossible with all the girls

except a beginner, Therese, who sat by my side. She was very timid