Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (23 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

Jessica Tandy and Elia Kazan backstage

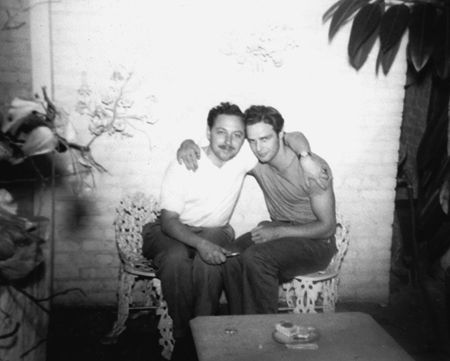

Embracing Marlon Brando at the “bad notice” party, 1948

Streetcar

’s success made Williams some kind of king. At the play’s opening-night party at the 21 Club, after the reviews had been read out and Williams had run the gauntlet of congratulations, Audrey Wood approached him. “Tenn, are you really happy?” she said.

’s success made Williams some kind of king. At the play’s opening-night party at the 21 Club, after the reviews had been read out and Williams had run the gauntlet of congratulations, Audrey Wood approached him. “Tenn, are you really happy?” she said.

Williams looked surprised. “Of course I am,” he said.

“Are you a completely fulfilled young man?”

“Completely,” Williams said. “Why do you ask me?”

“I just wanted to hear you say it,” Wood said.

From that moment on, for better or worse, Williams was on a first-name basis with the world. Everyone seemed to be at his table. He rarely signed himself “Tom”; he was “Tenn” or “10.” In May 1948, Williams won the Pulitzer Prize; in October, Margo Jones’s production of

Summer and Smoke

arrived on Broadway. After it was rumbled by most of the critics, Williams gave the failure the royal brush-off. He threw a catered “bad notice” party to which he invited “the critics who gave us the two worst notices.” “The party was really swell,” he wrote to Donald Windham.

Summer and Smoke

arrived on Broadway. After it was rumbled by most of the critics, Williams gave the failure the royal brush-off. He threw a catered “bad notice” party to which he invited “the critics who gave us the two worst notices.” “The party was really swell,” he wrote to Donald Windham.

At one point in the evening, Williams stole away to ride with Marlon Brando on his new motorcycle. Here, at the zenith of the century’s promise, in the time of their defining triumph, the greatest actor and the greatest playwright of their era sped around Manhattan feeling the exhilarating surge of power underneath them. Williams had embraced his sexuality and his talent; now he was embracing his new momentum. “I enjoyed the ride, clamping his buttocks between my knees as we flew across the East River and along the river drive with the cold wind whistling and a moon,” he said. Williams added, “My closest friends remained after the party—Jane, Tony, Sandy, Joanna, and the boy living with me named Frankie Merlo—Merlo means blackbird—and he is a Sicilian from New Jersey.”

CHAPTER 3

The Erotics of Absence

The desiring fingers enclose a phantom object, the hungering lips are pressed to a ghostly mouth.

—Tennessee Williams,

The Roman Spring of Mrs. Stone

My writing dealt with you. I lamented there only what I could not lament on your breast. It was an intentionally long farewell—which you forced out of me, but which I shaped . . .

—Franz Kafka,

Letter to His Father

On December 30, 1947—four weeks after the clamorous opening of

Streetcar

—Tennessee Williams sailed for Europe on the SS

America

. It was his first transatlantic trip abroad as an adult, and he was going solo. “I don’t intend to get seriously involved with anyone ever again,” he said.

Streetcar

had set off a seismic shift in American theater. It had also triggered a shift in the playwright himself. For Williams, who was now earning two thousand dollars a week in royalties, austerity and anonymity were things of the past. He was a first-class passenger. And no matter how far afield he traveled, the spotlight would always somehow find him. “My nights have been wild and wonderful in Manhattan, lasting always till five in the morning, seldom getting more than four or five hours sleep,” he wrote to Margo Jones once he was en route.

Streetcar

—Tennessee Williams sailed for Europe on the SS

America

. It was his first transatlantic trip abroad as an adult, and he was going solo. “I don’t intend to get seriously involved with anyone ever again,” he said.

Streetcar

had set off a seismic shift in American theater. It had also triggered a shift in the playwright himself. For Williams, who was now earning two thousand dollars a week in royalties, austerity and anonymity were things of the past. He was a first-class passenger. And no matter how far afield he traveled, the spotlight would always somehow find him. “My nights have been wild and wonderful in Manhattan, lasting always till five in the morning, seldom getting more than four or five hours sleep,” he wrote to Margo Jones once he was en route.

On the day of his departure, the attention that the other grandees of the theater lavished on Williams signaled his new power. Jessica Tandy, Kim Hunter, and Montgomery Clift showed up at the disorganized playwright’s apartment for “a packing-bee.” Elia Kazan arrived with champagne. Later, crowded into his stateroom, the group presented him with a dozen white shirts, a cashmere sweater, and a bottle of scotch. Clift brought with him a portable Hermes Baby typewriter—a gift from Margo Jones and a reminder, if Williams needed one, that it was time to get back to work on the rewrites for the upcoming Broadway production of

Summer and Smoke

.

Summer and Smoke

.

In Europe the parade of celebrities continued: Greta Garbo recommended his Paris hotel; Louis Jouvet, Jean-Louis Barrault, and Jean Cocteau—the nabobs of the French theater—turned up to dine with him. (When Williams threw a cocktail party for his famous Parisian friends, he noted dryly, “Sartre did not show up, although reported to be in the neighborhood.”) Paris, however, was a disappointment—“cold, bad food, no satisfactory company, no milk for my coffee.” Williams gave press interviews in his hotel bathtub—the water was warmer than the radiators. “I found nothing very good about Paris but the quality of the whores,” Williams wrote to Kazan. “You can fuck almost anything you lay your eyes on for the price of a black-market dollar.” He added, “There is no atmosphere of social unrest in Europe that I am able to sense. You feel no spark of any kind except the stubborn will to survive and you feel that they will support whichever party or doctrine offers them a chance to eat.”

When Williams fell ill during his first two weeks abroad, the editor of the fashion magazine

Elle

—a Madame Lazareff, whose husband owned

Paris Jour

and

Paris Soir

—packed him off for a week of rest and relaxation at the Colombe d’Or, in St.-Paul-de-Vence, where the dining room was a walled terrace garden dominated by a Léger frieze. It rained almost continuously. His first exposure to the sun was on the day he boarded the train in Nice and headed for Rome (“The

sun

—glorious sun—is on my face, in my eyes, and I love it”).

Elle

—a Madame Lazareff, whose husband owned

Paris Jour

and

Paris Soir

—packed him off for a week of rest and relaxation at the Colombe d’Or, in St.-Paul-de-Vence, where the dining room was a walled terrace garden dominated by a Léger frieze. It rained almost continuously. His first exposure to the sun was on the day he boarded the train in Nice and headed for Rome (“The

sun

—glorious sun—is on my face, in my eyes, and I love it”).

BY THE TIME Williams arrived in the Eternal City, fascism and the Second World War had more or less sealed it off as a destination point for the American traveler. Even in its ravaged, recuperative state, the city quickly became for Williams “the capitol of my heart.” “Here in Italy, this place of soft weather and golden light and of great bunches of violets and carnations sold on every corner and the Greek ideal surviving so tangibly in the grace and beauty of the people and the antique sculpture as well,” Williams wrote to Carson McCullers soon after arriving. “I cannot write coherently about Rome as I love it so much!”

For Williams, Rome was a “soft city,” tender and emollient in the blue transparency of its light, the skyline reminiscent to him of the eternal female: “domes of ancient churches, swelling above the angular roofs like the breasts of giant recumbent women, still bathed in gold light.” The warmth of the city extended to its people. “They do not hate Americans at all,” he wrote to Brooks Atkinson. “In fact the whole time I’ve been here I haven’t had an unfriendly word or look from any of them.”

After less than a month abroad, Williams wrote to Kazan, “I haven’t the slightest idea what I am doing over here, but if I were in the States I would probably be a lot more confused.” By the third month, however, his uncertainty had turned to impasse. He had fallen, he said later, “under the moon of pause.” “Sometimes the lamp burns very low indeed,” he confided to McCullers. “For the past five or six days I have been battering my head against a wall of creative impotence.” Sex, “the trapeze of the flesh,” as he called it, was his antidepressant; it swung him away from his writer’s block and into life. “You can’t walk a block without being accosted by someone you would spend a whole evening trying vainly to make in the New York bars,” he wrote to Windham, adding, “You may wonder how I ever get any work done here. The answer is I don’t get much.” Williams binged on boys.

Cruising, with its drama of enticement and evasion, of appearance and disappearance, was particularly thrilling in Rome. “In the evenings, very late, after midnight, I like to drive out the old Appian Way and park the car at the side of the road and listen to the crickets among the old tombs,” he wrote. “Sometimes a figure appears among them which is not a ghost but a Roman boy in the flesh!” “The nightingales busted their larynx!” he wrote to Oliver Evans, in a letter about a dark-haired Neapolitan lightweight boxer with an “imperial torso,” whom he had picked up. “I wish I could tell you more about this boxer, details, positions, amiabilities—but this pale blue paper would blush!” After throwing a few big parties that “turned into orgies,” Williams found himself an unwitting set piece in the local homosexual scene. “I remind myself of that lady who Oscar Wilde said had tried to establish a salon but only succeeded in opening a saloon,” he told Windham.

When Williams tried to characterize for James Laughlin the extraordinary Roman social whirl—which included new friendships with such expatriate Americans as the novelist Frederic Prokosch and “that unhappy young egotist Gore Vidal”—he spoke of “the ephemeral bird-like Italians, sweet but immaterial, like cotton-candy.” The excitement, for him, he explained, lay in savoring their immateriality, their ghostliness, their ability to vanish. “I shall remember all of them like one person who was very pleasant, sometimes even delightful, but like a figure in a dream, insubstantial, not even leaving behind the memory of a conversation: the intimacies somehow less enduring than the memory of a conversation, at least seeming that way now, but possibly later invested with more reality: ghosts in the present: afterwards putting on flesh, unlike the usual way.”

With Gore Vidal and Truman Capote, 1948

WILLIAMS HAD INTENDED his European sojourn as a way of shaking off the self-consciousness of his new celebrity, of getting “back under the dining-room table with a child’s beautifully clear eyes,” as John Updike described the purpose of travel for the successful writer. But the experience of Rome left him more wide-eyed than clear-eyed. “Italy has been a real experience, a psychic adventure of a rather profound sort which I shall be able to define in retrospect only,” he wrote to Laughlin. “I also have a feeling it is a real caesura: pause: parenthesis in my life: that it marks a division between two very different parts which I leave behind me with trepidation.”

Williams was no longer a one-hit wonder. The dimension of his success had left him stunned, struggling to retain the long-cherished notion of himself as fugitive outsider and to come to terms with the imperatives of celebrity. “Being successful and famous makes such demands!” he wrote to Audrey Wood. “I wanted it and still want it, with one part of me, but that isn’t the part of me that is important or creative.” Before his success, Williams had everything to fight for; now he had everything to defend. He had a public name and a public posture. “You know, then, that the public Somebody you are when you ‘have a name’ is a fiction created with mirrors and that the only somebody worth being is the solitary and unseen you that existed from your first breath and which is the sum of your actions and so is constantly in a state of becoming,” he wrote in the essay “On a Streetcar Named Success.” “The continual procession”—the visitors, the side trips, the rent boys—only magnified what Williams referred to as his “spiritual dislocation.”

By June 1948, when he went north for the English debut of

The Glass Menagerie

, he felt distracted and “as nervous as a cat.” “I am quite forlorn here. In spite of almost continual society,” he wrote to Windham from the Savoy Hotel in London. Britain’s drabness and snobbery sank his spirits. “To really appreciate Italy fully you should come to London first,” he wrote to Windham. “Christ, what a dull town and what stuffy people! I have actually been compelled to start working again, which is a sign of real ennui.”

The Glass Menagerie

, he felt distracted and “as nervous as a cat.” “I am quite forlorn here. In spite of almost continual society,” he wrote to Windham from the Savoy Hotel in London. Britain’s drabness and snobbery sank his spirits. “To really appreciate Italy fully you should come to London first,” he wrote to Windham. “Christ, what a dull town and what stuffy people! I have actually been compelled to start working again, which is a sign of real ennui.”

Other books

Lens of Time: Book 05 - Star Rover-The Worst of Time by Saxon Andrew

Deadly Contact by Lara Lacombe

Seduced by Pain by Alex Lux

The One Who Got Away by Jo Leigh

Murder in Vein (2010) by Jaffarian, Sue Ann

En El Hotel Bertram by Agatha Christie

Against the Season by Jane Rule

The Meltdown Match (A Romance Novella) by Anderson, Rachael

Europe: A History by Norman Davies