Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (82 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

The glaring difference between the vivacity of Williams’s early letters and his garrulous memoirs demonstrated an internal sea change: at the start of his career, Williams had survived to write; now, he wrote to survive. “

I can’t live in a professional vacuum, I must have new productions to make my life seem worth continuing a while longer—and the big one seems to be still a bit in the distance.

Lemme know, lemme know, lemme know!” he wrote to the producer Hillard Elkins in 1974 about

The Red Devil Battery Sign

, a political allegory begun in the radical upheaval of 1972 and optioned in its first draft in 1973 by David Merrick, who had produced Williams’s three previous Broadway flops.

I can’t live in a professional vacuum, I must have new productions to make my life seem worth continuing a while longer—and the big one seems to be still a bit in the distance.

Lemme know, lemme know, lemme know!” he wrote to the producer Hillard Elkins in 1974 about

The Red Devil Battery Sign

, a political allegory begun in the radical upheaval of 1972 and optioned in its first draft in 1973 by David Merrick, who had produced Williams’s three previous Broadway flops.

With all its dark, conspiratorial political overtones, the play, which is set in Dallas after the Kennedy assassination, allowed Williams to explore his sense of being, like his characters, a dead man walking. (“Did I die by my own hand or was I destroyed slowly and brutally by a conspiratorial group?” Williams wrote in his late “Mes Cahiers Noirs.” “Perhaps I was never meant to exist at all.”) His heroine, named only “Woman Downtown”—the rich, wayward wife of a nefarious industrial kingpin involved in political chicanery who keeps her under surveillance—recalls the corrupt bonhomie of the lavish parties she once hosted as “one big hell-hollering

death grin

.” “Oh, they trusted me to take their attaché cases with the payola and the secrets in code, and w

hy not? Wasn’t I perfectly NOT human, too?!

” she tells King, a bar pickup whose sexual connection to her brings her back to life. “Human!” she shouts, throwing her head back. King, who is struggling to recover from a brain tumor, was formerly the charismatic star turn of a mariachi band called the King’s Men, which featured Nina, his flamenco-dancing daughter. He dreams of singing again and of reclaiming his old glory. “Tonight? I got up on the bandstand with the men and I—

sang!

” he tells his wife, who has to support him now. “And there was applause almost like there was before. Soon I will send for La Niña and we will hit the road again. Remember her voice and mine together.”

death grin

.” “Oh, they trusted me to take their attaché cases with the payola and the secrets in code, and w

hy not? Wasn’t I perfectly NOT human, too?!

” she tells King, a bar pickup whose sexual connection to her brings her back to life. “Human!” she shouts, throwing her head back. King, who is struggling to recover from a brain tumor, was formerly the charismatic star turn of a mariachi band called the King’s Men, which featured Nina, his flamenco-dancing daughter. He dreams of singing again and of reclaiming his old glory. “Tonight? I got up on the bandstand with the men and I—

sang!

” he tells his wife, who has to support him now. “And there was applause almost like there was before. Soon I will send for La Niña and we will hit the road again. Remember her voice and mine together.”

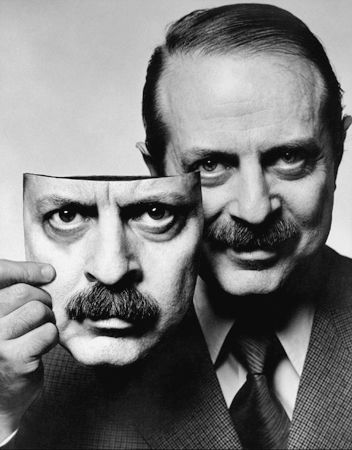

David Merrick, “the abominable showman”

In this daydream of corruption and redemption—a hallucinatory vision in which “grief and disease receive little pity, where men live in chronic dread and howl in city canyons like coyotes at the moon,” as Herbert Kretzmer wrote in London’s

Daily Express

when the play was performed there in 1977—the living dead are briefly shocked into new life. As King dies of a brain seizure, he manages to tell Woman Downtown, “Dreams necessary.” King loses his kingdom on earth; Downtown Woman, wild by nature and truthful in spirit, gains the kingdom of revolutionary immortality. At the finale, the play shifts from impressionistic reality to poetic prophesy. Woman Downtown is still a ghost of sorts, but one who haunts the audience with righteous outrage, joined hand in hand with the spectral protesting young—“outlaws in appearance . . . streaks of dirt on their faces, bloodied bandages, scant and makeshift garments.” The stage directions tell us, “They seem to explode from a dream—and the scene with them . . . eyes wide, looking out at us who have failed or betrayed them. . . . The Woman Downtown advances furthest to where King’s body has fallen. She throws back her head and utters the lost but defiant outcry of the she-wolf.”

Daily Express

when the play was performed there in 1977—the living dead are briefly shocked into new life. As King dies of a brain seizure, he manages to tell Woman Downtown, “Dreams necessary.” King loses his kingdom on earth; Downtown Woman, wild by nature and truthful in spirit, gains the kingdom of revolutionary immortality. At the finale, the play shifts from impressionistic reality to poetic prophesy. Woman Downtown is still a ghost of sorts, but one who haunts the audience with righteous outrage, joined hand in hand with the spectral protesting young—“outlaws in appearance . . . streaks of dirt on their faces, bloodied bandages, scant and makeshift garments.” The stage directions tell us, “They seem to explode from a dream—and the scene with them . . . eyes wide, looking out at us who have failed or betrayed them. . . . The Woman Downtown advances furthest to where King’s body has fallen. She throws back her head and utters the lost but defiant outcry of the she-wolf.”

Merrick and Williams struggled to find a director for this challenging, opaque melodrama, which Williams subtitled in its early drafts “A Work for the Presentational Theatre.” Williams wanted Milton Katselas or Elia Kazan; Merrick was pressing for Michael Bennett, a choreographer-turned-director who was best known at that time for his work on Neil Simon’s

Promises, Promises

. “He’s just 32—and at that age, how can he dig the depth of life and death which are inseparable from this play? I still love Gadg Kazan,” Williams wrote to Merrick. To Barnes, he said, “In the old days I usually had a director before I had a producer. . . . The director is invariably more objective than the author, especially an author like me who is full of anxiety and uncertainty, who even doubts the sun will come up tomorrow. None of these . . . incontestable facts have occurred to David.”

Promises, Promises

. “He’s just 32—and at that age, how can he dig the depth of life and death which are inseparable from this play? I still love Gadg Kazan,” Williams wrote to Merrick. To Barnes, he said, “In the old days I usually had a director before I had a producer. . . . The director is invariably more objective than the author, especially an author like me who is full of anxiety and uncertainty, who even doubts the sun will come up tomorrow. None of these . . . incontestable facts have occurred to David.”

Throughout the play’s gestation, Merrick treated Williams like a dead man. For critics to call Williams a ghost of his former self, or even, rhetorically, to declare him “dead,” was par for the course by the late seventies. But for Williams to be treated as invisible by a collaborator was an insult of an altogether different order. Merrick often refused to communicate directly with Williams or to answer his letters. “If the play has not your confidence and I have not your friendship, then maybe I should just concentrate on the approach of the Christmas season and go back to New Orleans and continue work on the play,” Williams wrote to him in November 1973, adding, “I thought we had arrived at the point where you could call me but I still hear nothing from you. . . . This is not the way an important play is prepared.”

Emotionally and artistically, Merrick and Williams had reached an impasse. That December, with no production scheduled and no director assigned, the momentum of the play seemed to have evaporated. Williams wrote to Kazan for help: “I sensed that you were seriously interested in the play. Of course it would add to my feeling of security—and I am sure of Merrick’s, too—if you would make some sort of commitment, no, I don’t mean commitment but printed statement of ‘involvement’—such as ‘Tennessee is going to Mexico to pull an exciting long play together, and if he is not raped or slaughtered by lascivious and blood-thirsty bandits, I might resume my directorial activity, that is, if Tennessee and I are both convinced that he has pulled the opus together.’—Well, you don’t have to phrase it that eloquently, but some sort of little item in

Variety

or the

Times

would vastly increase my momentum and also the public interest.”

Variety

or the

Times

would vastly increase my momentum and also the public interest.”

But Kazan didn’t take the bait, and Merrick continued to drag his feet. “What’s the matter, David? Don’t you have the money?” St. Just brazenly asked the producer, who, according to his biographer, “seemed to choke on her words.” On August 18, 1974, after Merrick’s option lapsed, Barnes saw the opportunity to jump ship to the team that had just given Williams a spectacular success with a London revival of

A Streetcar Named Desire

, starring Claire Bloom and directed by Ed Sherin. Hillard Elkins, the revival’s producer, who was then Bloom’s husband, began negotiations for

Red Devil

, a move that so outraged Merrick that he threatened to sue for breach of contract, until Williams agreed to extend his option. “None of us wanted to be involved in litigation with such a moneyed and powerful man,” he said. In the end, for a while, Merrick and Elkins joined forces. By then, Williams’s director of choice was Sherin, who considered

Red Devil

“one of the most important works of the decade, with a clear warning about the destructive forces rampant in our society,” but who was unwilling to commit if Merrick was the sole producer. “I felt that David Merrick hadn’t the patience, understanding or compassion to produce this particular work,” Sherin said, who pushed Elkins to do the play alone. Elkins insisted that he could work with Merrick and that Sherin’s feelings “were paranoid.”

A Streetcar Named Desire

, starring Claire Bloom and directed by Ed Sherin. Hillard Elkins, the revival’s producer, who was then Bloom’s husband, began negotiations for

Red Devil

, a move that so outraged Merrick that he threatened to sue for breach of contract, until Williams agreed to extend his option. “None of us wanted to be involved in litigation with such a moneyed and powerful man,” he said. In the end, for a while, Merrick and Elkins joined forces. By then, Williams’s director of choice was Sherin, who considered

Red Devil

“one of the most important works of the decade, with a clear warning about the destructive forces rampant in our society,” but who was unwilling to commit if Merrick was the sole producer. “I felt that David Merrick hadn’t the patience, understanding or compassion to produce this particular work,” Sherin said, who pushed Elkins to do the play alone. Elkins insisted that he could work with Merrick and that Sherin’s feelings “were paranoid.”

Red Devil

was scheduled to begin tryouts in Boston in mid-June 1975, then travel to Washington, and open on Broadway in August, with a star-studded cast that included Anthony Quinn, Katy Jurado, and Claire Bloom. Setting off for rehearsals in New York, Williams wrote to St. Just, “I fancy this will be a summer of drama, mostly offstage.” And so it proved. Merrick, who was also acting as the company manager, demanded that the set be redone by a new set designer; the union would not allow the hiring of Mexican mariachis, and the New York variety turned out not to read music; Katy Jurado found it difficult to pronounce or to understand Williams’s words; and Bloom, whose acting style didn’t mix well with Quinn’s, was having trouble finding her character. One afternoon during rehearsals, Quinn took Sherin aside and suggested that “another actress be found or he would leave,” Sherin said, adding, “Four days before we travelled to Boston, the play was unrealized, the acting was uneven, the mariachis were nowhere, but we were going to perform for the public the following Saturday.” At one of these unhappy rehearsals, Merrick put in a rare appearance. “As I live and breathe, it’s Mr. Broadway,” Williams drawled. Merrick shot him a look. “I thought you said you’d be dead before we went into rehearsals,” he said. Williams replied, “Never listen to a duck in a thunderstorm.”

was scheduled to begin tryouts in Boston in mid-June 1975, then travel to Washington, and open on Broadway in August, with a star-studded cast that included Anthony Quinn, Katy Jurado, and Claire Bloom. Setting off for rehearsals in New York, Williams wrote to St. Just, “I fancy this will be a summer of drama, mostly offstage.” And so it proved. Merrick, who was also acting as the company manager, demanded that the set be redone by a new set designer; the union would not allow the hiring of Mexican mariachis, and the New York variety turned out not to read music; Katy Jurado found it difficult to pronounce or to understand Williams’s words; and Bloom, whose acting style didn’t mix well with Quinn’s, was having trouble finding her character. One afternoon during rehearsals, Quinn took Sherin aside and suggested that “another actress be found or he would leave,” Sherin said, adding, “Four days before we travelled to Boston, the play was unrealized, the acting was uneven, the mariachis were nowhere, but we were going to perform for the public the following Saturday.” At one of these unhappy rehearsals, Merrick put in a rare appearance. “As I live and breathe, it’s Mr. Broadway,” Williams drawled. Merrick shot him a look. “I thought you said you’d be dead before we went into rehearsals,” he said. Williams replied, “Never listen to a duck in a thunderstorm.”

Red Devil

didn’t make it to Broadway or even to Washington. Its first Boston preview, on June 14, 1976, was four hours long, and even the director judged it “amateurish, ponderous, inaccurate and incomplete.” When it opened on June 18, critical opinion was mixed, with reactions varying from “a mess” (the

Boston

Globe

) to “cause for rejoicing . . . a haunting theatre piece” (

Christian Science Monitor

). Nonetheless, the audiences were lively and at near capacity. Then, just as the play was “beginning to emerge,” according to Sherin, Merrick announced that the entire $360,000 investment had been spent and that there might not be enough left over to cover the cost of closing. (According to Sherin, his co-producer subsequently claimed that “only $260,000 or less had been spent.”)

didn’t make it to Broadway or even to Washington. Its first Boston preview, on June 14, 1976, was four hours long, and even the director judged it “amateurish, ponderous, inaccurate and incomplete.” When it opened on June 18, critical opinion was mixed, with reactions varying from “a mess” (the

Boston

Globe

) to “cause for rejoicing . . . a haunting theatre piece” (

Christian Science Monitor

). Nonetheless, the audiences were lively and at near capacity. Then, just as the play was “beginning to emerge,” according to Sherin, Merrick announced that the entire $360,000 investment had been spent and that there might not be enough left over to cover the cost of closing. (According to Sherin, his co-producer subsequently claimed that “only $260,000 or less had been spent.”)

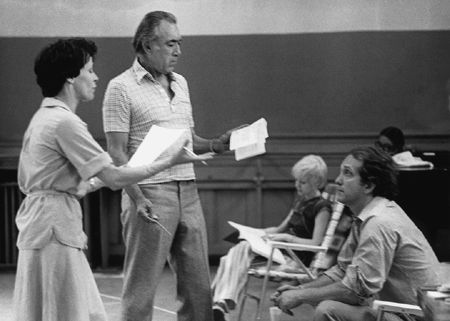

Claire Bloom, Anthony Quinn, and Ed Sherin rehearse

The Red Devil Battery Sign

The Red Devil Battery Sign

Ostensibly to save the production, Merrick presented a plan that would require the creative team to make drastic cuts to royalties and the actors’ salaries. When Merrick’s numbers were challenged, he refused to show his books and countered with the threat that if his plan was not immediately adopted, he would remove the equipment he personally owned (all the lights and the winches used in set changes). In a late-night eeting that weekend, peace between the management and the cast seemed to be negotiated; but on Merrick’s orders at 7:00 P.M. on Monday, at the beginning of the run’s second week, a closing notice was posted. “I stood in disbelief, before moving on to all the dressing rooms to assure the company that there had been some mistake,” Sherin wrote. “Claire Bloom, who only drinks wine occasionally, was downing a shot of vodka from a freshly opened bottle on her dressing-room table. Anthony Quinn was seething with anger and talked bitterly of a double-cross. The notice must have been all the more bitter for Quinn, when at the final curtain that night, he received a standing ovation for his performance as King.”

That Tuesday, Sherin called Williams to tell him the bad news. “He gave me this shocking report of a statement by Merrick. He declared before witnesses that he had always hated me and the play and that he had only produced it to destroy it. Mr. Sherin is not a man to invent such a story,” Williams wrote in a memo to himself. “If Merrick does indeed think that he has destroyed the play, I think he is totally unaware of my dedication to my work, the tenacity of my resolve to resist its destruction. I have many enemies; but I feel these enemies are greatly out-numbered by those who understand and admire the work which [is?] the heart or truth of my being.” Williams added, “Bill Barnes invited me over last night to inform me of the posted notice. We sat upon his terrace as dusk fell. . . . It was a curiously emotionless occasion.” Other members of the production were not so laid back. Quinn told a reporter, “Tennessee Williams, one of the great talents of all time, has been treated like an assembly-line butcher.” Sherin saw Merrick’s draconian actions as indicative of the ominous undertow of a corrupt culture, “the very forces in our society about which Tennessee Williams is writing in ‘The Red Devil Battery Sign,’ ” he said. “If these forces are already so powerful that they can silence the warnings of our greatest artists, then it may already be too late.”

Red Devil

ended its Boston run on June 28, 1975, the first Williams play to close out of town since

Battle of Angels

, thirty-five years earlier. “It’s not closing for good,” Merrick told a reporter from the

New York

Times

. “It’s closing for bad.” When the play was staged in a tighter, angrier, more political version by the English Theatre in Vienna in 1975—“Burn, burn, burn,” the cast chanted at the finale—it was praised as “one of the most thrilling tragedies of love and hate in Williams’s work” (

Frankfurter Allgemeine

) and “a blazing torch illuminating the very core of life” (

Die Presse

). But in the society at which Williams’s howling vision was aimed,

Red Devil

went unheard and unnoticed.

ended its Boston run on June 28, 1975, the first Williams play to close out of town since

Battle of Angels

, thirty-five years earlier. “It’s not closing for good,” Merrick told a reporter from the

New York

Times

. “It’s closing for bad.” When the play was staged in a tighter, angrier, more political version by the English Theatre in Vienna in 1975—“Burn, burn, burn,” the cast chanted at the finale—it was praised as “one of the most thrilling tragedies of love and hate in Williams’s work” (

Frankfurter Allgemeine

) and “a blazing torch illuminating the very core of life” (

Die Presse

). But in the society at which Williams’s howling vision was aimed,

Red Devil

went unheard and unnoticed.

Other books

Leviathan by Scott Westerfeld

Spooky Little Girl by Laurie Notaro

G'Day to Die by Maddy Hunter

The Goldsmith's Daughter by Tanya Landman

Doghouse by L. A. Kornetsky

The Veil by Bowden, William

The Tooth Fairy by Joyce, Graham

Convergence Point by Liana Brooks

Dark Horse by Michelle Diener