Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (13 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

The particular barrenness of Williams’s life in this period—a spectacular deprivation that is mirrored in

Summer and Smoke

by Alma’s housebound social and emotional imprisonment—led him to a kind of living death of resignation, “enduring for the sake of endurance,” as Alma puts it. Faced with his own solitude and his sexual starvation, in a direct echo of Alma’s words, Williams vowed, “Now I must make a positive religion of the simple act of

endurance

—I must endure & endure &

still endure

.” Williams, by his own admission, was “an expert at graceful retreat but at vigorous assault I’m rather pathetically unskilled.”

Summer and Smoke

by Alma’s housebound social and emotional imprisonment—led him to a kind of living death of resignation, “enduring for the sake of endurance,” as Alma puts it. Faced with his own solitude and his sexual starvation, in a direct echo of Alma’s words, Williams vowed, “Now I must make a positive religion of the simple act of

endurance

—I must endure & endure &

still endure

.” Williams, by his own admission, was “an expert at graceful retreat but at vigorous assault I’m rather pathetically unskilled.”

Like Alma, who suffers from all kinds of psychosomatic symptoms—heart trouble, insomnia, nervousness, ennui—Williams was plagued by a series of complaints that signaled his quiet desperation. The aridity of life reduced him to “a strange trance-like existence” and pushed him to a numbed point where, as he wrote, “the heart forgets to feel even sorrow after a while.” “The dreadful heavy slipping by of the days like oxen on a hot dusty road toward some possible spring—dreadfully athirst but not knowing where the water is hidden,” he wrote. “Oh strange and dreadful caravan of tired cattle—Quo Vadis?—Where? Why?—What!!” Alma “was caging in something that was really quite different from her spinsterish, puritanical nature,” Williams said in 1961; so was he. His 1939 notebook is full of longing but no courage to act on it. “I need somebody to envelop me, embrace me, pull me by sheer force out of this neurotic shell of fear I’ve built around myself lately,” he wrote. “I feel all but annihilated. Yes, something

does

have to break and damn soon or I

will

.”

does

have to break and damn soon or I

will

.”

Williams had to unlearn repression; this meant doing battle with the congenital shyness that prevented him from showing or knowing his feelings. “What taunts me most is my inability to make contact with the people, the world,” he wrote in his diary. “I remain one and separate among them. My tongue is locked. I float among them in a private dream and shyness forbids speech and union. This is not always so. A sudden touch will release me. Once out, I am free and approachable. I need the solvent.” Williams had grown up on a confounding diet of rejection and idealization, which had left him unconfident about the allure of his essential nature. “I am so used to being a worm,” he wrote in 1937. Later, he explained, “I’ve never had any feeling of sexual security.” “I’m only attracted to androgynous males. . . . I find women much more interesting than men, but I’m afraid to try to fuck women now. . . . Because women aren’t as likely as the androgynous male to give you sexual reassurance. With a boy who has the androgynous quality in spirit, like a poet, the thing is more spiritual. I need that.” (As late as 1943, despite the fact that he was a produced playwright and a contract writer for MGM, he still wondered to his diary why someone like the publisher of New Directions, Jay Laughlin, would seek him out and want to be friends. “It is so easy to ignore a squirt like me.”) Experience had taught him, he said, that “to know me is not to love me.” “I am a problem to anybody who cares anything about me—Most of all to myself who am, of course, my only ardent lover (though a spiteful and a cruel one!)”

Eventually, Williams, like Alma, found release in male pickups and a life of profligacy. At first, however, Williams struggled in vain against his homosexual nature. “I am as pure as I ever was—in fact purer—essentially—Ah, well . . . ” At the end of 1939, he noted, “Thank god I’ve gotten bitch-proof.”

By February 1940, alternately thrilled and appalled, Williams had joined the sexual merry-go-round. “My first real encounter was in New Orleans at a New Year’s Eve party during World War Two,” Williams recalled. “A very handsome paratrooper climbed up to my grilled veranda and said, ‘Come down to my place’ and I did, and he said, Would you like a sunlamp treatment? And I said, Fine, and I got under one and he proceeded to do me. That was my coming out and I enjoyed it.” He had said good-bye to the ascetic aspect of his prolonged adolescence, but the hello to his adult sexual instincts took some adjustment. “Ashes hauled,” he wrote in his diary. “Somehow pretty sick of it.” Two weeks later, noticing in the mirror that his boy self was evaporating, he wrote, “Oh, Lord, I don’t know what to make of this life I’m living. Things

happen

but they don’t add up to much. . . . I’m getting ugly though. My face looks so heavy and coarse these days. I feel that my youth is nearly gone. Now when I need it most!” With sex, Williams noted, “the restless beast in the jungle under the skin, comes out for a little air.”

happen

but they don’t add up to much. . . . I’m getting ugly though. My face looks so heavy and coarse these days. I feel that my youth is nearly gone. Now when I need it most!” With sex, Williams noted, “the restless beast in the jungle under the skin, comes out for a little air.”

Williams had liberated his desire, only to be lumbered by appetite. “I ache with desires that never are quite satisfied,” he wrote. “This promiscuity is appalling really. One night stands. Nobody seems to care particularly for an encore.” He added, “Still waiting for the big thing to come along.” Sex, he was learning, was a way of discharging aggression. Love didn’t enter into the equation. “The big emotional business is still on the other side of tomorrow,” he wrote. “That’s why I’m restless. Maybe tropical sunlight—or moonlight—would stir something up that I’m in need of. Shit.” By mid-1940, “this awful searching-business of our lives” was no easier for Williams. “My emotional life has been a series of rather spectacular failures,” he wrote in his diary. “Last night was the grand anti-climax—Ah, l’amour, la guerre et la vie!! When will it happen—and how?” He added, “Haggard, tired, jittery, fretful, bored—that is what lack of a reciprocal love object does to a man. Let us hope it spurs his creative impulse—there should be

some

compensation for this hell of loneliness. Makes me act, think,

be

like an idiot—whining, trivial, tiresome.” He scrawled in his notebook, “

You

coming toward me—

please

make

haste!

J’ai soif! Je meurs de soif!

”

some

compensation for this hell of loneliness. Makes me act, think,

be

like an idiot—whining, trivial, tiresome.” He scrawled in his notebook, “

You

coming toward me—

please

make

haste!

J’ai soif! Je meurs de soif!

”

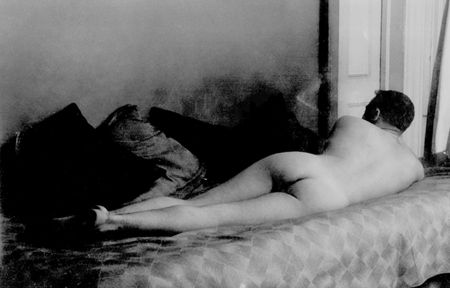

Williams in the flesh, 1943

Williams soon took to his new lifestyle like a bass to a top-water lure. Once he was fortified by a few drinks, his congenital shyness evaporated. “His practice in a room of half a dozen more or less presentable males was to make a pass at the one he found most attractive and then, if it was not successful, to go on down the line,” Windham recalled. Windham continued, “If none of these approaches was successful, there were still the showers and steam rooms at the Y.” Williams recalled cruising Times Square with Windham. “He would dispatch me to street corners where sailors or GIs were grouped, to make very abrupt and candid overtures, phrased so bluntly that it’s a wonder they didn’t slaughter me on the spot,” Williams wrote. “Sometimes they mistook me for a pimp soliciting for female prostitutes and would respond ‘Sure, where’s the girls?’—and I would have to explain that they were my cruising partner and myself. Then, for some reason, they would stare at me for a moment in astonishment, burst into laughter, huddle for a brief conference, and, as often as not, would accept this solicitation, going to my partner’s Village pad or to my room at the Y.” According to Windham, during these early wolfish years, Williams’s “quotidian goal was to end up in bed with a partner at least once before the twenty-four hours was over.”

In less than fifteen months, Williams went from prude to lewd. “I was just terribly over sexed, baby, and terribly repressed,” Williams told

Playboy

. “I’m getting horny as a jack-rabbit,” he wrote to Windham in October 1940, from the arid confines of the family home, where, ironically, his mother and grandmother—“the most uncompromising of southern Puritans . . . seem to believe it my sacred and peculiar mission to eliminate sex from the modern theatre.” He went on, “So line up some of that Forty-second Street trade for me when I get back!” Once in New York, in his diaries, the image of satyr alternated with that of a sad sack. From a man-child unwilling even to touch himself, he had progressed to “deviant Satyriasis,” as he referred to his sexual rampage

.

“Sexuality is an emanation, as much in the human being as the animal,” he said. “Animals have a season for it. But for me it was a round-the-calendar thing.”

Playboy

. “I’m getting horny as a jack-rabbit,” he wrote to Windham in October 1940, from the arid confines of the family home, where, ironically, his mother and grandmother—“the most uncompromising of southern Puritans . . . seem to believe it my sacred and peculiar mission to eliminate sex from the modern theatre.” He went on, “So line up some of that Forty-second Street trade for me when I get back!” Once in New York, in his diaries, the image of satyr alternated with that of a sad sack. From a man-child unwilling even to touch himself, he had progressed to “deviant Satyriasis,” as he referred to his sexual rampage

.

“Sexuality is an emanation, as much in the human being as the animal,” he said. “Animals have a season for it. But for me it was a round-the-calendar thing.”

“I went out cruising last night and brought home something with a marvelous body,” he wrote to Paul Bigelow. “It was animated Greek marble and turned over even. It asked for money and I said, Dear, would I be living in circumstances like this if I had any money?” Sometimes, Williams’s lovers were startled by the beating of Williams’s own hungry heart. “I am always alarming bed partners by having palpitations,” he wrote. “Tonight my pulse was taken by the alarmed guest and it was counted ‘over 100.’ Considerably over I guess. I am so used to it it doesn’t disturb me except when it makes me breathless. Well, tonight was worth palpitations. An almost ideal concurrence of circumstances and a record for me of 5 times perfectly reciprocal pleasure.”

“As the world grows worse it seems more necessary to grasp what pleasure you can, to be selfish and blind, except in your work,” he wrote to Windham. In his romantic imagination, this was a belief that would develop into something like a full-blown religion. “I’d like to live a simple life—with epic fornications,” he wrote in 1942. “I think for a good summer fuck you should cover the bed with a large white piece of oil-cloth,” he wrote the same year. “The bodies of the sexual partners ought to be thoroughly, even superfluously rubbed over with mineral oil or cold cream. It should be in the afternoon, preferably soon after lunch when the brain is dull. . . . It should be a bright, hot day, not far from the railroad depot and the scene of the fornication should be a Victorian bedroom at the top of the house with a skylight letting the sun directly down on the bed. . . . If the sexual partner is a southern belle with intellectual pretensions and a beautiful ass, it must be plainly told where the charm is concentrated and urged to keep the loftier cerebral processes out of the picture at least till after the first ejaculation. This little item is from my Mother’s Recipe Book, on the page for meat dishes.”

However, whenever Williams’s lecherous smile was met with cold teeth, he grew dispirited. “I cruised with 3 flaming belles for a while on Canal Street and around the Quarter,” he wrote in 1941. “They bored and disgusted me so I quit and left Saturday night to its own vulgar, noisy devices.” Sometimes, Williams met not with pleasure but with violence. “Tonight ran into some ‘dirt’ at the Polynesian bar—for the first time in my life I was struck—not hard enough to hurt anything but my spirit,” he wrote. “Close shave. Returned to the safety of ‘James’ Bar’ where I met the companion of last night and we resumed our cruising—again fruitless for me.”

IN

YOU TOUCHED ME!

Williams wrote of “unspent tenderness” growing and growing “until it gets to be something enormous. Then finally there is so much of it. It explodes inside them—and they go to pieces.” He knew the feeling. “When I now appear in public, the children are called indoors and the dogs pushed out!” he wrote to a friend in 1941. “My cumulated sexual potency is sufficient to blast the Atlantic fleet out of Brooklyn. . . . I have never felt quite so rape-lusty.” In a sense Williams’s promiscuity served as a sort of powerful antidepressant; it provided a sense of external adventure to a life that seemed to him internally stalled. In his poem “The Siege,” written in the early forties, Williams, who did not like or trust his body, described his blood as mercury, an unstable element that can’t hold its shape and needs to be contained:

YOU TOUCHED ME!

Williams wrote of “unspent tenderness” growing and growing “until it gets to be something enormous. Then finally there is so much of it. It explodes inside them—and they go to pieces.” He knew the feeling. “When I now appear in public, the children are called indoors and the dogs pushed out!” he wrote to a friend in 1941. “My cumulated sexual potency is sufficient to blast the Atlantic fleet out of Brooklyn. . . . I have never felt quite so rape-lusty.” In a sense Williams’s promiscuity served as a sort of powerful antidepressant; it provided a sense of external adventure to a life that seemed to him internally stalled. In his poem “The Siege,” written in the early forties, Williams, who did not like or trust his body, described his blood as mercury, an unstable element that can’t hold its shape and needs to be contained:

Sometimes I feel the island of my self

a silver mercury that slips and runs

revolving frantic mirrors in itself

beneath the pressure of a million thumbs.

Then I must that night go in search of one

unknown before but recognized on sight

whose touch, expedient or miracle,

stays panic in me and arrests my flight.

As the poem suggests, Williams didn’t seem to know just what was inside him—and he needed to be inside someone else in order to piece together his fragmented self. “I always want my member to enter the body of the sexual partner,” Williams said. “I’m an aggressive person, I want to give, and I think it should be reciprocal.” His sexual delirium had about it a sense of both panic and primness. “In his room, amid the disordered contents of his suitcase and footlocker trunk, he kept, besides a jar of Vaseline, a bottle of Cuprex, against crabs, and a tube of prophylactic salve, against gonorrhea. A small drawstring bag, like the bags cigarette tobacco was sold in then, accompanied the tube of salve, to tie around his genitals and protect his clothing when he dressed after the salve was applied,” Windham wrote of Williams during his prowling days at the Y. He added, “When he was not on the make and trying to charm, his behavior frequently suggested that he had never been part of any family, and certainly never under the supervision of a punctilious mother who was a Regent of the D.A.R.—Daughters of the American Revolution.” On the contrary, like Williams’s habit of sucking his teeth, licking his lips, and eating when he pleased—“I think I have gone as far toward release from dogmatic strictures as anyone goes,” he confided to his diary—promiscuity was another way of forgetting home and its deadly climate of repression.

Other books

Sunlight on the Mersey by Lyn Andrews

An Old Pub Near the Angel by Kelman, James

Rogue Elements by Hector Macdonald

Alexander Mccall Smith - Isabel Dalhousie 05 by The Comforts of a Muddy Saturday

Division Zero by Matthew S. Cox

Feedback by Mira Grant

The Guardians by Ashley, Katie

Misperception (Finnegan Brothers Book 3) by Black, Morgan

Translucent by Erin Noelle

Tome of Bill (Companion): Shining Fury by Gualtieri, Rick