Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (35 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

STELLA: We’re not going back in there. Not this time. We’re never going back. Never, never back, never back again.

And then Stella turns and proceeds with strength and confidence up the stairs to Eunice’s apartment.

Although this change ensured the PCA’s rating of “acceptable,” the Legion of Decency, a Catholic watchdog organization, whose self-proclaimed concern was “the primacy of moral order” but which had no statutory rights of censorship, objected to something much thornier and more fundamental in Williams’s play: the erotic charge of the flesh. The sizzle of Stanley and Stella’s coupling, not the brutality meted out to Blanche, was what threatened

Streetcar

with the Legion’s C (Condemned) rating. “Joe, a very strange thing has happened,” Vizzard wrote to Breen, after being tipped off about the Legion’s complaints. “In concentration on our two leading characters, with whom most of the problems lay, we completely missed what this bastard Kazan was doing with Stella . . . the lustful and carnal scoring they introduced into the final print underscores and highlights what were mere subtleties and suggestions in a way I never thought possible.” He continued, “The result is to throw into sharp relief in the finished film the purely lustful relationship between Stella and Stanley, that creates a totally different impression from the one we got when we saw it. . . . It makes it a story about sex—sex desire specifically—and this is the quintessence of the objection by the Legion.”

Streetcar

with the Legion’s C (Condemned) rating. “Joe, a very strange thing has happened,” Vizzard wrote to Breen, after being tipped off about the Legion’s complaints. “In concentration on our two leading characters, with whom most of the problems lay, we completely missed what this bastard Kazan was doing with Stella . . . the lustful and carnal scoring they introduced into the final print underscores and highlights what were mere subtleties and suggestions in a way I never thought possible.” He continued, “The result is to throw into sharp relief in the finished film the purely lustful relationship between Stella and Stanley, that creates a totally different impression from the one we got when we saw it. . . . It makes it a story about sex—sex desire specifically—and this is the quintessence of the objection by the Legion.”

Warner Brothers panicked. At the rumor of the Legion’s disapproval, Radio City Music Hall canceled

Streetcar

’s grand opening. The studio imagined pickets, yearlong boycotts, and priests stationed in lobbies taking the names of parishioners who attended. “When you speak of the primacy of moral values, my only question is: WHOSE?” Kazan wrote to the Legion’s spokesman, Martin Quigley, in August 1951, a month before the film’s release. “My only objection is to a situation in which, regardless of motive, the effect is the imposition of the values of one group of our population upon the rest of us. This limits one of our fundamental American rights: freedom of expression.” Kazan added, “This, to my way of thinking, is immoral.” Quigley, who was an editor of a motion-picture trade paper and a Catholic with strong personal ties to Cardinal Francis Spellman, the Archbishop of New York, fired back, “You asked

whose

moral values I am talking about. I refer to the long-prevailing standards of morality of the Western World, based on the Ten Commandments—nothing, you see, that I can boast of inventing or dreaming up. . . . I have the same right to say that the moral consideration has a right of precedence over the artistic consideration as you have to deny it.”

Streetcar

’s grand opening. The studio imagined pickets, yearlong boycotts, and priests stationed in lobbies taking the names of parishioners who attended. “When you speak of the primacy of moral values, my only question is: WHOSE?” Kazan wrote to the Legion’s spokesman, Martin Quigley, in August 1951, a month before the film’s release. “My only objection is to a situation in which, regardless of motive, the effect is the imposition of the values of one group of our population upon the rest of us. This limits one of our fundamental American rights: freedom of expression.” Kazan added, “This, to my way of thinking, is immoral.” Quigley, who was an editor of a motion-picture trade paper and a Catholic with strong personal ties to Cardinal Francis Spellman, the Archbishop of New York, fired back, “You asked

whose

moral values I am talking about. I refer to the long-prevailing standards of morality of the Western World, based on the Ten Commandments—nothing, you see, that I can boast of inventing or dreaming up. . . . I have the same right to say that the moral consideration has a right of precedence over the artistic consideration as you have to deny it.”

In an attempt to do an end run around the Legion of Decency, Kazan made a proposal to Jack Warner. Since the Legion had publicly argued that it was imposing its rating only for the protection of its flock, Kazan argued that the studio “should take them at their word.” His idea was to open

Streetcar

in two different New York theaters: one showing the “condemned version” for the general public and the other showing an approved Legion of Decency version for Catholic audiences. “Think about it. Aside from everything else, I think it is great showmanship,” Kazan wrote to his boss. “I even think some Catholics might sneak in to see the condemned version. I think it would gain you and your organization the respect of 98% of this country,

including most of the Catholics

. . . . I was brought up a Catholic in New Rochelle, New York, went to catechism school for two years, and am very intimately acquainted with nuns and priests. Believe me,

they like everybody else

despise no one so much as the people who knuckle under to them. In that respect they are only human.”

Streetcar

in two different New York theaters: one showing the “condemned version” for the general public and the other showing an approved Legion of Decency version for Catholic audiences. “Think about it. Aside from everything else, I think it is great showmanship,” Kazan wrote to his boss. “I even think some Catholics might sneak in to see the condemned version. I think it would gain you and your organization the respect of 98% of this country,

including most of the Catholics

. . . . I was brought up a Catholic in New Rochelle, New York, went to catechism school for two years, and am very intimately acquainted with nuns and priests. Believe me,

they like everybody else

despise no one so much as the people who knuckle under to them. In that respect they are only human.”

Nothing came of Kazan’s suggestion, however. Instead, a week before the film’s opening, on September 18, 1951, without informing Kazan, Jack Warner dispatched a film editor to New York to carry out twelve cuts suggested by the Legion, which amounted to four minutes of film. “They range from a trivial cut of three words ‘on the mouth’ (following the words ‘I would like to kiss you softly and sweetly’) to a re-cutting of the wordless scene in which Stella, played by Kim Hunter, comes down a stairway to Stanley after a quarrel,” Kazan wrote in an article on the subject in the

New York

Times

. “This scene was carefully worked out in an alternation of close and medium shots, to show Stella’s conflicting revulsion and attraction to her husband and Miss Hunter played it beautifully. The censored version protects the audience from the close shots and substitutes a long shot of her descent. It also, by explicit instruction, omits a wonderful piece of music. It was explained to me that both the close shots and the music made the girl’s relation to her husband ‘too carnal.’ ” Kazan continued, “Another cut comes directly before Stanley attacks Blanche. It takes out his line, ‘You know, you might not be bad to interfere with.’ Apart from forcing a rather jerky transition, this removes the clear implication that only here, for the first time, does Stanley have any idea of harming the girl. This obviously changes the interpretation of the character, but how it serves the cause of morality is obscure to me, though I have given it much thought.”

New York

Times

. “This scene was carefully worked out in an alternation of close and medium shots, to show Stella’s conflicting revulsion and attraction to her husband and Miss Hunter played it beautifully. The censored version protects the audience from the close shots and substitutes a long shot of her descent. It also, by explicit instruction, omits a wonderful piece of music. It was explained to me that both the close shots and the music made the girl’s relation to her husband ‘too carnal.’ ” Kazan continued, “Another cut comes directly before Stanley attacks Blanche. It takes out his line, ‘You know, you might not be bad to interfere with.’ Apart from forcing a rather jerky transition, this removes the clear implication that only here, for the first time, does Stanley have any idea of harming the girl. This obviously changes the interpretation of the character, but how it serves the cause of morality is obscure to me, though I have given it much thought.”

In exchange for issuing a B rating, the Legion also insisted that the director’s version not be shown at the Venice Film Festival. Outraged by this demand, and buoyed by the film’s subsequent commercial and artistic success (it was nominated for Academy Awards in six categories, including Best Director), Kazan refused to let the issue drop. “My picture had been cut to fit the specifications of a code which is not my code, is not a recognized code of the picture industry, and is not the code of the great majority of the audience,” Kazan wrote in the

Times

article, blowing the whistle on the studio’s perfidy. Decades later, in his autobiography, Kazan recalled the incident and its implications. “The Legion of Decency had acted with a boldness and an openness that were unusual for them,” he wrote. “What it meant—and I didn’t immediately recognize this—was that the strength and confidence of the right in the entertainment world was growing stronger.” The rising power of the Right, with its strategy of secrecy and intimidation, destabilized the cultural atmosphere. “Now an air of dissolution settled everywhere around me,” Kazan noted. “From sources I didn’t know, mysterious pressures were attacking the professional lives and, as a consequence, so it seemed, the personal relations of many of my friends. . . . Chaos was in the air.”

Times

article, blowing the whistle on the studio’s perfidy. Decades later, in his autobiography, Kazan recalled the incident and its implications. “The Legion of Decency had acted with a boldness and an openness that were unusual for them,” he wrote. “What it meant—and I didn’t immediately recognize this—was that the strength and confidence of the right in the entertainment world was growing stronger.” The rising power of the Right, with its strategy of secrecy and intimidation, destabilized the cultural atmosphere. “Now an air of dissolution settled everywhere around me,” Kazan noted. “From sources I didn’t know, mysterious pressures were attacking the professional lives and, as a consequence, so it seemed, the personal relations of many of my friends. . . . Chaos was in the air.”

On May 18, 1951, Williams set sail for Rome. His retreat from America was a measure of his increasing sense of oppression at home. “It seems to me that the very things that make it uncomfortable for you here in the States are the things that make you write,” Kazan wrote in a letter criticizing Williams’s impulse to flee. “It seems to me that the things that make a man want to write in the first place are those elements in his environment, personal or social, that outrage him, hurt him, make him bleed. Any artist is a misfit. Why the hell would he go to all the trouble if he could make the ‘adjustment’ in a ‘normal’ way? In Rome, I’d say, you felt a kind of suspension of discomfort. . . . You are not really Tennessee Williams in Rome. . . . Blanche was a fragile white moth beating against the unbreakable sides of a 1000 watt bulb. But in Rome the 1000 watt bulb doesn’t exist. The moth is more or less at home. . . . Whether you like it or not, and in a way, especially since you do not, you should stay here in the States. I think you’d soon have some new plays writing that NO ONE could turn you off.”

It was a turbulent time. A month earlier, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg had been sentenced to death for allegedly passing a design for the atomic bomb to the Soviets, and in Korea, the Chinese and the United States were nearing a stalemate on either side of the thirty-eighth parallel. But Williams wasn’t interested in making political statements; he worked from the inside out. Politics existed, like most of his relationships, somewhere on the periphery of his work, “a sort of penumbra outside the central mania.” His plays wrestled with history only insofar as the contour of the times paralleled his internal drama. Abroad, during Williams’s “summer of wanderings,” a cold war of an altogether different kind loomed. “Yesterday was the first time in our lives together that I’ve known him to act like a bitch, and a rather usual one at that,” Williams noted in his diary about Merlo’s increasing truculence. “Of course there have been ‘signs’, now, for a number of months, but the resentment, the discontent—whatever it is—and he is still an enigma to me—are more and more exercised and displayed, now even publicly, adding humiliation to confusion, insecurity and sorrow. I can only wonder.”

Like all factotums to the famous, Merlo was both needed and unacknowledged; he was trapped between empowerment and alienation. Throughout the rehearsals and the opening of

The Rose Tattoo

, he steadfastly supported the frantic Williams. But anything he did to help Williams only maximized the disparity between them. With the success of

The Rose Tattoo

, which was inspired by and about him, Merlo found it impossible to hide his ambivalence. Williams got the glory; Merlo got the grief. In Key West, before leaving for Europe, he dutifully oversaw the household affairs first for Williams’s family, who had struggled with the flu during their stay, then for Rose and her caretaker, who visited. In order to relieve Merlo of some of his ever-increasing responsibilities, Williams hired the unflappable Leoncia McGee as cook and housekeeper, a position she held devotedly until Williams’s death, in 1983. (Leoncia, Williams wrote, “makes the foulest coffee that ever made a man take to drink! It seems to be a distillation of volcanic ash. Tastes horrible but is so strong it blows your lid after the first dreadful swallow.”) But Leoncia’s presence in the eccentric ménage left Merlo even more restless; losing his daily chores, he also lost part of his identity. He now had no purpose. He was both the beneficiary of Williams’s largesse and its captive. The glamour of their life—the famous friends, the exciting events, the travel—was to Merlo both a pleasure and a perpetual reminder of his own powerlessness. Inevitably, he kicked against his golden cage. Neither he nor Williams wanted to understand that his sudden disaffection (which he denied when Williams confronted him about it) was an envious attack on Williams and his writing. By making it hard for Williams to work, Merlo unconsciously was robbing him of some of his power and control.

The Rose Tattoo

, he steadfastly supported the frantic Williams. But anything he did to help Williams only maximized the disparity between them. With the success of

The Rose Tattoo

, which was inspired by and about him, Merlo found it impossible to hide his ambivalence. Williams got the glory; Merlo got the grief. In Key West, before leaving for Europe, he dutifully oversaw the household affairs first for Williams’s family, who had struggled with the flu during their stay, then for Rose and her caretaker, who visited. In order to relieve Merlo of some of his ever-increasing responsibilities, Williams hired the unflappable Leoncia McGee as cook and housekeeper, a position she held devotedly until Williams’s death, in 1983. (Leoncia, Williams wrote, “makes the foulest coffee that ever made a man take to drink! It seems to be a distillation of volcanic ash. Tastes horrible but is so strong it blows your lid after the first dreadful swallow.”) But Leoncia’s presence in the eccentric ménage left Merlo even more restless; losing his daily chores, he also lost part of his identity. He now had no purpose. He was both the beneficiary of Williams’s largesse and its captive. The glamour of their life—the famous friends, the exciting events, the travel—was to Merlo both a pleasure and a perpetual reminder of his own powerlessness. Inevitably, he kicked against his golden cage. Neither he nor Williams wanted to understand that his sudden disaffection (which he denied when Williams confronted him about it) was an envious attack on Williams and his writing. By making it hard for Williams to work, Merlo unconsciously was robbing him of some of his power and control.

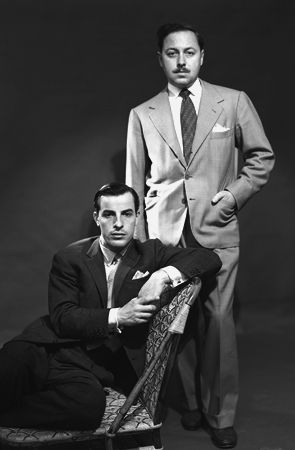

With Merlo,

Vogue

session, 1949

Vogue

session, 1949

For part of the summer, Merlo insisted that he and Williams go their separate ways. “He is not at all keen on seeing me at present,” Williams noted in his diary on July 25. “It is unfortunate for me that this emotional dislocation had to come at a moment in my life when I most needed someone to give me the security that I used to feel in thinking myself cared for.” Williams continued later the same day, “I called F. He made or suggested

no

appointment to meet. I feel as alone as a man must feel at the moment of his death. I know he will never really

say

—I will just have to try to guess what’s happened, what I’ve done, what’s wrong between us. I have no home but him. Can I find another? Can I live without one?”

no

appointment to meet. I feel as alone as a man must feel at the moment of his death. I know he will never really

say

—I will just have to try to guess what’s happened, what I’ve done, what’s wrong between us. I have no home but him. Can I find another? Can I live without one?”

In his letters Williams referred to this period as “the summer of the long knives.” Wood had an appendectomy, Oliver Evans had an ear operation, Britneva an abortion, Paul Bigelow had surgery on his jaw, and Williams himself almost ended up on an operating table. In late July, heading from Rome to the Costa Brava, Williams drove his Jaguar into a tree at seventy miles an hour. “I had been quite witless for several days prior to the accident and should not have started out, but I felt that only a change could pull me together,” he told Kazan. “So I filled a thermos with martinis and hit the highway.” What happened next he recounted to Wood: “About one hundred miles out of Rome I became very nervous. I took a couple—or was it three?—stiff drinks from a thermos I had with me, and the first thing I knew there was a terrific crash! . . . It was amazing that I was not seriously injured. My portable typewriter flew out of the back seat and landed on my head. Only a small cut, no concussion, but the typewriter badly damaged!—Ever since, from the shock, I suppose, I have been very tense.”

In Venice, recovering from the accident and “almost panicky with depression,” Williams vowed to “be sweet to acquaintances and so to make friends.” To get through the nerve-wracking string of evenings he had arranged with Peggy Guggenheim and Harold Clurman and his wife, the actress Stella Adler, Williams drank heavily. By day, he contemplated his loneliness, his self-loathing, and his boozing, adapting his “term in Purgatory” into a story called “Three against Grenada,” a meditation on “Southern Drinkers,” specifically a young Mississippian of “great vigor and promise,” Brick Bishop, who succumbs to alcoholism. (The story, extensively rewritten and retitled “Three Players of a Summer Game,” was published fifteen months later in

The

New Yorker

and became the basis for

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

.) Brick’s hapless hanging-on mirrored Williams’s bewildered mood. “No one noticed Mr. Brick Bishop and he noticed nothing; his eclipse was total,” Williams wrote of Brick.

The

New Yorker

and became the basis for

Cat on a Hot Tin Roof

.) Brick’s hapless hanging-on mirrored Williams’s bewildered mood. “No one noticed Mr. Brick Bishop and he noticed nothing; his eclipse was total,” Williams wrote of Brick.

Other books

Ex-Patriots by Peter Clines

Anytime Soon by Tamika Christy

Blood Awakening by Jamie Manning

Tom Paine Maru - Special Author's Edition by L. Neil Smith

Anna's Contract by Deva Long

Mad Love (Hearts Are Wild): Hearts Are Wild by Rhian Cahill

Stranger in the Room: A Novel by Amanda Kyle Williams

El señor del carnaval by Craig Russell

The Betrayed by Igor Ljubuncic

Against the Odds by Brenda Kennedy