Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (48 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

Anna Magnani as the seamstress Serafina in

The Rose Tattoo

The Rose Tattoo

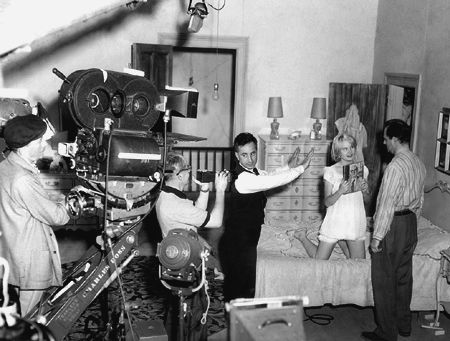

From November 1955 to January 1956, Kazan was in Benoit, Mississippi (population 341), filming

Baby Doll

. He took his family with him for the ten-week shoot; he had trouble, however, coaxing Williams away from Key West. “Those people chased me out of there. I left the South because of their attitude towards me. They don’t approve of homosexuals, and I don’t want to be insulted,” he told Kazan. Nonetheless, he eventually turned up, only to excuse himself after a couple of restless days with the canard that he couldn’t find a place to swim. “God damn it, I need an ending to this film,” Kazan told him. Williams was distracted from the new play he had begun by the imminent opening of a production of

Streetcar

, starring Tallulah Bankhead and playing at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami, that was billed as “under the supervision of Tennessee Williams,” and by the glitzy New York premiere of the movie

The Rose Tattoo

, featuring the legendary Magnani’s debut in American cinema. He seemed to want to be left more or less alone; so, really, did Kazan. “Now I was without an author, but I didn’t mind,” he recalled in

A Life

. “I was what I wanted to be, the source of everything.”

Baby Doll

. He took his family with him for the ten-week shoot; he had trouble, however, coaxing Williams away from Key West. “Those people chased me out of there. I left the South because of their attitude towards me. They don’t approve of homosexuals, and I don’t want to be insulted,” he told Kazan. Nonetheless, he eventually turned up, only to excuse himself after a couple of restless days with the canard that he couldn’t find a place to swim. “God damn it, I need an ending to this film,” Kazan told him. Williams was distracted from the new play he had begun by the imminent opening of a production of

Streetcar

, starring Tallulah Bankhead and playing at the Coconut Grove Playhouse in Miami, that was billed as “under the supervision of Tennessee Williams,” and by the glitzy New York premiere of the movie

The Rose Tattoo

, featuring the legendary Magnani’s debut in American cinema. He seemed to want to be left more or less alone; so, really, did Kazan. “Now I was without an author, but I didn’t mind,” he recalled in

A Life

. “I was what I wanted to be, the source of everything.”

On December 18, nearly a week after

The Rose Tattoo

premiere, Kazan sent Williams the scenes leading up to his proposed ending for

Baby Doll

. “There is one small element here following that you never had in any of your bits, scraps, versions, rewrites or letters,” he told him. That “small element,” it turned out, was a big narrative deal. Archie Lee Meighan (Karl Malden) wins the hand in marriage of Baby Doll (Carroll Baker)—a nubile, manipulative nymphet of nineteen who still sleeps in her nursery crib—by promising her father that he will not attempt to consummate the union until she’s twenty. It’s a vow that drives the loutish, sex-starved Archie Lee to distraction. In the meantime, as an act of revenge, Baby Doll is pursued by Silva Vacarro (Eli Wallach, making his screen debut), a man whose cotton gin Archie Lee has burned down. Although the film leaves open the question of whether he actually seduces Baby Doll, there’s no question about the sexual heat generated between her and the Italian interloper. In Kazan’s proposed ending, Archie Lee, thinking he’s been cuckolded, shoots up Vaccaro’s place in a fit of fury, accidentally killing a black man before continuing his search for Vacarro—a finale that Kazan felt would be “both tragic and funny, El Greco and Hogarth, tiny and gigantic.”

The Rose Tattoo

premiere, Kazan sent Williams the scenes leading up to his proposed ending for

Baby Doll

. “There is one small element here following that you never had in any of your bits, scraps, versions, rewrites or letters,” he told him. That “small element,” it turned out, was a big narrative deal. Archie Lee Meighan (Karl Malden) wins the hand in marriage of Baby Doll (Carroll Baker)—a nubile, manipulative nymphet of nineteen who still sleeps in her nursery crib—by promising her father that he will not attempt to consummate the union until she’s twenty. It’s a vow that drives the loutish, sex-starved Archie Lee to distraction. In the meantime, as an act of revenge, Baby Doll is pursued by Silva Vacarro (Eli Wallach, making his screen debut), a man whose cotton gin Archie Lee has burned down. Although the film leaves open the question of whether he actually seduces Baby Doll, there’s no question about the sexual heat generated between her and the Italian interloper. In Kazan’s proposed ending, Archie Lee, thinking he’s been cuckolded, shoots up Vaccaro’s place in a fit of fury, accidentally killing a black man before continuing his search for Vacarro—a finale that Kazan felt would be “both tragic and funny, El Greco and Hogarth, tiny and gigantic.”

Elia Kazan setting up a shot with Carroll Baker and Karl Malden on the Mississippi set of

Baby Doll

Baby Doll

Kazan’s idea was sensational, commercial, and bad; Williams was right back in the artistic tug of war he’d had over

Cat

. He showed no timidity, this time, in fighting his corner. “I simply can’t believe that you have been shooting a film that demands a finish like this outline,” Williams wrote, adding, “You say that whenever I am in trouble I go poetic. I say whenever you are in trouble, you start building up a ‘

SMASH!

’ finish.—As if you didn’t really trust the story that goes before. It is only this final burst of excess that mars your film-masterpieces such as ‘East of Eden,’ and it is in these final fireworks that you descend (only then) to something expected or banal which all the preceding artistry and sense of measure and poetry—yes, you are a poet, too! no matter how much you hate it!—leads one

not

to expect.” Kazan’s attention-grabbing finale was a piece of cinematic showboating, violent hokum that introduced a discordant note into Williams’s

comédie humaine

. “Not false to the country. The hell with the Delta!” Williams said. “But false to the key and mood of the story.” He went on, “Killing a negro is not a part of universal human behavior, witness all the universal Archie Lees in this world who never killed a negro and never

quite

would! They would commit arson, yes, they would lie and cheat and jerk off back of a peep-hole, but they wouldn’t be likely to kill a negro and slam the car door on his dying body and go on shooting and shouting, now, would they?! . . . A killing is not so much a moral discrepancy as it is an artistic outrage of the film-play’s natural limits.” Williams suggested something more in keeping with the story’s comic tone and scale—like Archie Lee blasting his shotgun at a car, then opening the car door to discover a black man inside, and saying, “Oh, it’s you! Excuse me.” Williams’s version appears in the film; Kazan’s does not.

Cat

. He showed no timidity, this time, in fighting his corner. “I simply can’t believe that you have been shooting a film that demands a finish like this outline,” Williams wrote, adding, “You say that whenever I am in trouble I go poetic. I say whenever you are in trouble, you start building up a ‘

SMASH!

’ finish.—As if you didn’t really trust the story that goes before. It is only this final burst of excess that mars your film-masterpieces such as ‘East of Eden,’ and it is in these final fireworks that you descend (only then) to something expected or banal which all the preceding artistry and sense of measure and poetry—yes, you are a poet, too! no matter how much you hate it!—leads one

not

to expect.” Kazan’s attention-grabbing finale was a piece of cinematic showboating, violent hokum that introduced a discordant note into Williams’s

comédie humaine

. “Not false to the country. The hell with the Delta!” Williams said. “But false to the key and mood of the story.” He went on, “Killing a negro is not a part of universal human behavior, witness all the universal Archie Lees in this world who never killed a negro and never

quite

would! They would commit arson, yes, they would lie and cheat and jerk off back of a peep-hole, but they wouldn’t be likely to kill a negro and slam the car door on his dying body and go on shooting and shouting, now, would they?! . . . A killing is not so much a moral discrepancy as it is an artistic outrage of the film-play’s natural limits.” Williams suggested something more in keeping with the story’s comic tone and scale—like Archie Lee blasting his shotgun at a car, then opening the car door to discover a black man inside, and saying, “Oh, it’s you! Excuse me.” Williams’s version appears in the film; Kazan’s does not.

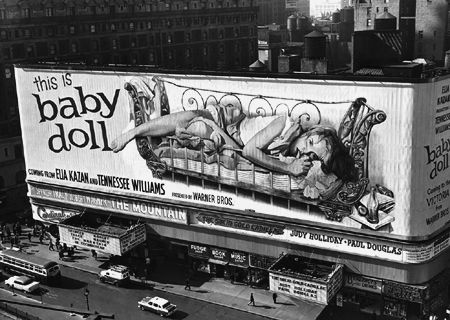

When it came to promoting the movie, however, Kazan the showman—

Baby Doll

was the first picture produced by his newly formed Newtown Productions—won out. He had a billboard about the size of the Statue of Liberty (15,600 square feet, a third of an acre) built above the Victoria Theatre on Broadway, where the movie debuted. It was the biggest painted sign in the world. “No one showboats anymore,” he swaggered to Warner Brothers. “Trust my instinct.”

Baby Doll

was the first picture produced by his newly formed Newtown Productions—won out. He had a billboard about the size of the Statue of Liberty (15,600 square feet, a third of an acre) built above the Victoria Theatre on Broadway, where the movie debuted. It was the biggest painted sign in the world. “No one showboats anymore,” he swaggered to Warner Brothers. “Trust my instinct.”

Kazan thought he had made “a very cute movie.” The Catholic Church, however, thought he’d made a very evil one. The Legion of Decency rated it C for “Condemned.” Without ever having seen the film, Cardinal Spellman took to the pulpit of St. Patrick’s Cathedral to denounce it. “I exhort Catholic people to refrain from patronizing this film under pain of sin,” the Cardinal said. “The revolting theme of this picture, ‘Baby Doll,’ and the brazen advertising promoting it, constitute a contemptuous defiance of the natural law, the observance of which has been the source of strength in our national life.” (Williams’s brother, Dakin, then an officer in the Air Force and a recent Catholic convert, had to pay the church twenty-five dollars for a dispensation to see the film.) The tabloids spewed boldface headlines. “ ‘BABY DOLL’ IN NEW ROW,” the

New York

Post

shouted from its front page. En route to the premiere on December 18—“a harrowing experience”—Williams weighed in. “I cannot believe that an ancient and august branch of the Christian faith is not larger in heart and mind than those who set themselves up as censors of a medium of expression that reaches all sections and parts of our country and extends the world over.” Kazan declared, “I am outraged by the charge that it is unpatriotic. In the court of public opinion, I’ll take my chance.”

New York

Post

shouted from its front page. En route to the premiere on December 18—“a harrowing experience”—Williams weighed in. “I cannot believe that an ancient and august branch of the Christian faith is not larger in heart and mind than those who set themselves up as censors of a medium of expression that reaches all sections and parts of our country and extends the world over.” Kazan declared, “I am outraged by the charge that it is unpatriotic. In the court of public opinion, I’ll take my chance.”

What remained in public memory, over time, was not the film itself but the billboard. The behemoth image of Carroll Baker, sprawled the length of a city block in her short nightie, sucking her thumb, and reclining in a crib, became as iconic an erotic emblem of the era as Marilyn Monroe holding down her billowing white skirt in

The Seven Year Itch

. “This is the greatest idea since the days of Barnum,” Kazan told Warner Brothers when he pitched the billboard; the sign, he assured the studio, would make

Baby Doll

“the talk not only of Broadway, but of the show world, of café society, of the literati, of the lowbrows, and of everybody else. I really don’t see how anyone could avoid going to the picture if we put that sign up there.” Kazan was right about the sign, wrong about the film. Generally speaking, the critical response to

Baby Doll

was muted. (Nowadays, Williams’s half-heartedness is all too apparent in the strained, lackluster dark comedy.) Controversy, however, never hurt the box office.

Baby Doll

made news and money; it also made Williams a subject of scandal. The

New Republic

christened the film “The Crass Menagerie.” “Just possibly the dirtiest American-made motion picture that has ever been legally exhibited,”

Time

said.

Baby Doll

had no nudity, no simulated sex, no foul language, and little violence; by contemporary standards, it was Simon Pure. Nonetheless, in the popular mind, thanks as much to the sensational sign as to the story, the film became synonymous with louche sex. In the

New Republic

, Williams found himself dubbed “the high priest of

merde

.” The attention only drove up his literary stock. MGM offered him another half-million dollars for his new play, still in its unfinished first draft. Every ignominy, Williams was learning, fueled his fame; likewise, fame fueled his ignominy.

The Seven Year Itch

. “This is the greatest idea since the days of Barnum,” Kazan told Warner Brothers when he pitched the billboard; the sign, he assured the studio, would make

Baby Doll

“the talk not only of Broadway, but of the show world, of café society, of the literati, of the lowbrows, and of everybody else. I really don’t see how anyone could avoid going to the picture if we put that sign up there.” Kazan was right about the sign, wrong about the film. Generally speaking, the critical response to

Baby Doll

was muted. (Nowadays, Williams’s half-heartedness is all too apparent in the strained, lackluster dark comedy.) Controversy, however, never hurt the box office.

Baby Doll

made news and money; it also made Williams a subject of scandal. The

New Republic

christened the film “The Crass Menagerie.” “Just possibly the dirtiest American-made motion picture that has ever been legally exhibited,”

Time

said.

Baby Doll

had no nudity, no simulated sex, no foul language, and little violence; by contemporary standards, it was Simon Pure. Nonetheless, in the popular mind, thanks as much to the sensational sign as to the story, the film became synonymous with louche sex. In the

New Republic

, Williams found himself dubbed “the high priest of

merde

.” The attention only drove up his literary stock. MGM offered him another half-million dollars for his new play, still in its unfinished first draft. Every ignominy, Williams was learning, fueled his fame; likewise, fame fueled his ignominy.

The

Baby Doll

billboard in Times Square

Baby Doll

billboard in Times Square

THE YEAR THAT ended in a public fracas over

Baby Doll

had begun, in January, with another one involving the fifty-four-year-old Tallulah Bankhead, who was playing Blanche in

Streetcar

at the Coconut Grove Playhouse. “She is the bitch of all time, but what a worker!” Williams wrote to Wood, after he was banned from rehearsals. From the outset, Williams had muddied the water between Bankhead and himself by bringing Britneva to Florida for the opening of a production for which she had unsuccessfully auditioned as Stella. “From the moment Miss Bankhead saw Maria, she would have none of her,” Sandy Campbell wrote in

B

, a privately printed epistolary account to his partner Donald Windham about the production in which he had a small part. “Tenn is licking his lips with the prospect of an encounter.”

Baby Doll

had begun, in January, with another one involving the fifty-four-year-old Tallulah Bankhead, who was playing Blanche in

Streetcar

at the Coconut Grove Playhouse. “She is the bitch of all time, but what a worker!” Williams wrote to Wood, after he was banned from rehearsals. From the outset, Williams had muddied the water between Bankhead and himself by bringing Britneva to Florida for the opening of a production for which she had unsuccessfully auditioned as Stella. “From the moment Miss Bankhead saw Maria, she would have none of her,” Sandy Campbell wrote in

B

, a privately printed epistolary account to his partner Donald Windham about the production in which he had a small part. “Tenn is licking his lips with the prospect of an encounter.”

On opening night—a performance that was overrun by Bankhead’s rowdy camp followers—Williams came into her dressing room, got down on his knees, put his head in her lap, and said, “Tallulah this is the way I imagined the part when I wrote the play.” At a party in honor of the cast that evening, however, according to Campbell, a juiced-up Williams, “in a voice all nearby (about a hundred or so people) could hear,” told Jean Dalrymple that if B[ankhead] continued to give such an appalling performance he would not allow the play to open in New York. She was “playing it for vaudeville and ruining my play.” Campbell added, “Maria, naturally . . . talking violently against B’s performance.” Inevitably, there was a showdown: Williams, who had hypocritically praised her, now told Bankhead she’d given a bad first-night performance. Campbell, who was present, recounted the scene:

“And you had the nerve to say that after getting down on your knees to me in the dressing room,” B said.

“Are you calling me a hypocrite? . . .”

“And bringing that bitch, Maria, to the party is shocking,” B said.

Tenn, standing up: “My dear, I do not have to stand for this anymore. Calling . . . my best friend a black bitch is more than I will take!” And he marched out.

Other books

Promises Under the Peach Tree (Harlequin Superromance) by Joanne Rock

One Fine Cowboy by Joanne Kennedy

Ghost Granny by Carol Colbert

Chef by Jaspreet Singh

Servants’ Hall by Margaret Powell

House at the End of the Street by Lily Blake, David Loucka, Jonathan Mostow

Changing My Mind by Zadie Smith

She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me by Brockes, Emma

Dead Little Dolly by Elizabeth Kane Buzzelli