Terror in the City of Champions (28 page)

Read Terror in the City of Champions Online

Authors: Tom Stanton

At the fight’s start, with the cold autumn air above the ring clouded with cigar and cigarette smoke, Louis looked across at Baer in dark trunks adorned with a white Star of David and saw a man “scared to death.”

From the ring an announcer told the crowd, “Although Joe Louis is colored, he is a great fighter, in the class of Jack Johnson and the giants of the past. . . . American sportsmanship, without regard to race, creed or color, is the talk of the world. Behave like gentlemen, whoever wins.” About a third of the audience was black. Seconds later Louis landed a left uppercut. He knew then he had control of the fight. Louis drew blood in the second round and nearly knocked out Baer in the third. The bell saved him. The men in his corner revived him enough to return. Louis finished him in the next round. Baer “fell like a marionette whose string had snapped,” wrote Grantland Rice. He managed to get to one knee but no further. It was the first time he had been knocked out.

Black America celebrated. From Harlem to Paradise Valley blacks poured out of their homes and into the streets laughing, clapping, cheering, screaming, singing, drinking, blowing horns, clanging pots, and voicing unadulterated joy. “It was twice as noisy as the coming of New Years to Times Square—and twice as happy,” said one observer. “He’s the Brown Embalmer now,” said a cabdriver.

In Chicago writer Richard Wright witnessed a bold torching of pride: “Something had popped loose, all right. And it had come from deep down. Out of the darkness it had leaped from its coil. And nobody could have said just what it was, and nobody wanted to say. Blacks and whites were afraid. But it was sweet fear, at least for the blacks. It was a mingling of fear and fulfillment. Something dreaded and yet wanted. A something had popped out of a dark hole, something with a hydra-like head, and it was darting forth its tongue.” A similar scene played out in Detroit, where Louis’s mother had listened to the fight on the radio.

The following weekend Louis was back in the city. On Sunday he and Marva went to Calvary Baptist Church where his family worshipped. Word had spread before and during the service. Two thousand five hundred Detroiters packed into the church. Another 5,000 gathered outside along Joseph Campau and Clinton Roads. The celebration was being piped outdoors. Louis was to speak about sons and mothers, but the mere sight of him at the front of the church caused such a blissful uproar that he couldn’t get out a word. Parishioners crowded around Louis.

“Since President Lincoln freed the slaves,” said visitor Sherman Walker, a pastor from Buffalo, “there hasn’t been a one of the race made as much of his talents as Joe Louis. Yes, sir, he’s a powerful man himself and for his people.”

The 1920s saw Detroit’s skyline explode with new buildings. By the 1930s the city was America’s fourth largest.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

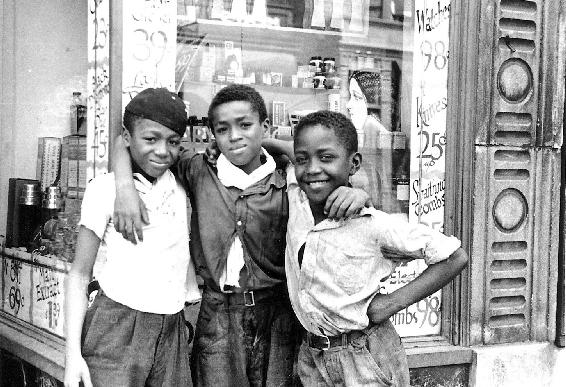

In the 1930s the majority of black Detroiters, like these children, lived in the east-side Black Bottom or Paradise Valley neighborhoods.

EDWARD STANTON

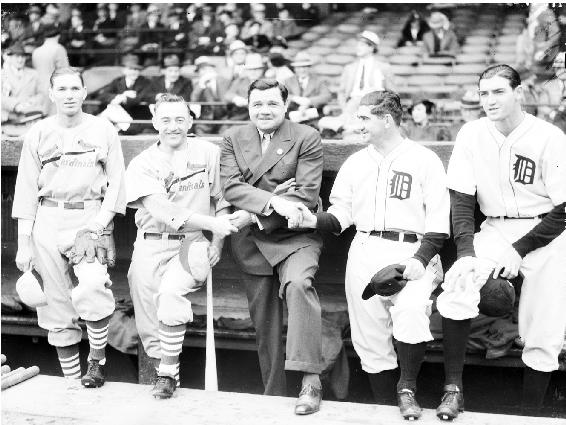

Before the 1934 World Series, Babe Ruth greets the managers and their star pitchers: Dizzy Dean and Frankie Frisch of the Cardinals and Mickey Cochrane and Schoolboy Rowe of the Tigers.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

Comic Will Rogers visits Henry and Edsel Ford before the start of a 1934 World Series game.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

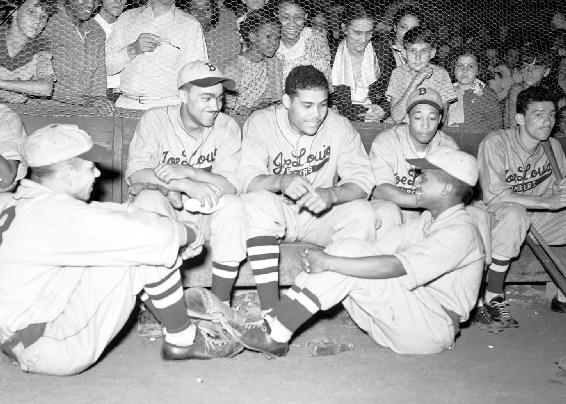

Joe Louis (center without a cap) started a barnstorming softball team that carried his name. He populated it with talented friends, many of whom were otherwise unemployed, and he played with them when his boxing schedule allowed.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

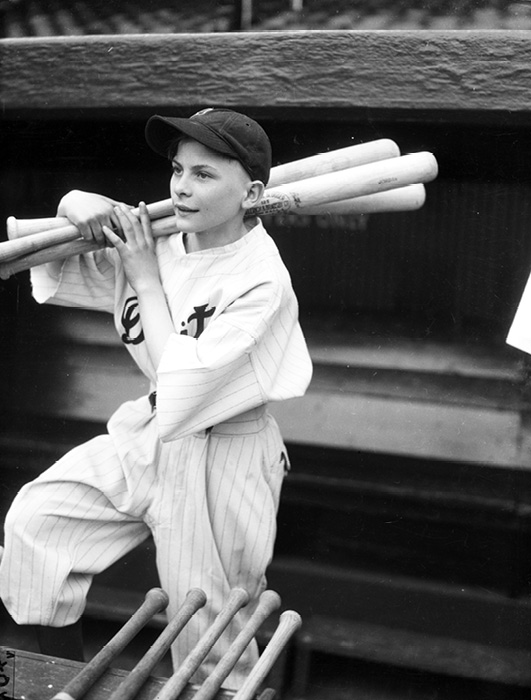

Tigers batboy Joey Roginski, who called himself Joey Roggin because of anti-Polish sentiment, became Hank Greenberg’s goodluck charm in the mid-1930s.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

Hank Greenberg and Joe Louis joke around before a 1935 Tigers game. Louis, a devoted baseball fan, was a frequent presence at Navin Field.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY

At spring training in Florida, Mickey Cochrane shares a laugh in the dugout.

WALTER P. REUTHER LIBRARY, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY