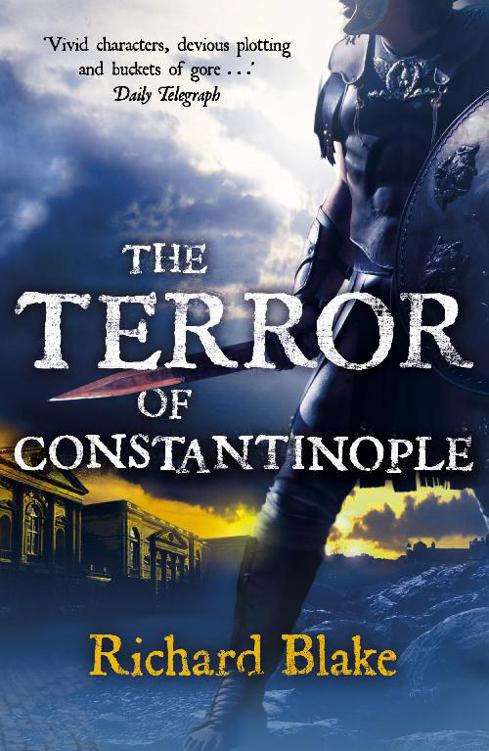

Terror of Constantinople

The Terror of Constantinople

Richard Blake

First published in Great Britain in 2009 by Hodder & Stoughton

An Hachette Livre UK company

Copyright © Richard Blake 2009

The right of Richard Blake to be identified as the Author

of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance

with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means

without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated

in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and

without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All characters in this publication are fictitious

and any resemblance to real persons,

living or dead, is purely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

Epub ISBN 978 1 848 94828 0

Book ISBN 978 0 340 95119 4

Hodder & Stoughton Ltd

338 Euston Road

London NW1 3BH

To my dear wife Andrea and to our daughter Philippa, without whose patience this novel would never have been written

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The two quoted lines in Chapter 24 are from

Antigone

by Sophocles (Author’s translation)

The two abusive epigrams in Chapter 31 are by the Author

The quotation in Chapter 32 of the lines from

Oedipus the King

by Sophocles is from the translation by Francis Storr (1839–1919)

The translation in Chapter 36 of the lines by Sappho is by the Author

The quotation in Chapter 43 ascribed to Euripides is from A.E. Housman (1859–1936),

Fragment of a Greek Tragedy

The poem in Chapter 59 ascribed to Simonides is by A.E. Housman,

More Poems

, 1936, XXXVI

PROLOGUE

Monday, 16 April 686

‘Why are you crying, Master?’ Bede asked me this morning. Though knocking as usual, he’d brought in the hot water before I could sit up properly in bed and compose my features.

‘A complaint of age, my child,’ I replied with a weak stab at the enigmatic. The absence of light coming through the shutters confirmed it was raining again. That’s all it ever seems to do in Northumbria. It falls in a gentle mist that blurs the landscape and soaks you before you can notice. I can hardly remember when I last spent a whole day reading in the sun.

In silence, I washed my hands and face, and stood shivering as Bede stretched up and rubbed at my frail, withered body. Time was – and not too long ago – when that would have banished all misery. Nowadays, the most solitary pleasures often evade my grasp.

‘I’ve missed morning prayers again,’ I said, to break the silence.

‘My Lord Abbot said to leave you sleeping. He told me you were late to bed.’

So Benedict had noticed that jug of beer I’d grabbed off the dinner table. I grunted and held my arms apart so Bede could start dressing me.

‘There is fresh bread today, Master,’ he added. ‘Even so, I made sure to steep it well in the milk.’

‘I thank you, my child,’ I said. I ran my tongue over sore gums and wondered how long before I was entirely confined to curds and stewed fruit. When you reach ninety-five, there are very few teeth you haven’t outlived. ‘But I’ll eat shortly. For the moment, let us proceed with your lesson.’

I thought briefly, then recited a passage from Cicero at his most rhetorically florid. I paused at every natural break in the flow, letting Bede keep up with me as, eyes squeezed shut, he committed the text to his own memory. This done, I let him continue in the time-honoured manner – parsing and analysis of grammar, rare or difficult words explained, their etymology given, and so forth. Whenever he stumbled, I intervened with just enough explanation to set him right again. My interventions grew decreasingly frequent, and then only on points that would tax a much older student than Bede.

He’s a bright lad. He reminds me of myself. If he lives, he’ll be the glory of his age.

As the lesson moved smoothly on like a carriage in the grooves of a much-travelled road, I began to feel better. I hadn’t at first been able to remember why, but I had woken crying. It was the dreams, you see. They’d been in sharper colours and more painful since I arrived here. Memory isn’t like a religious text, where passages are separated into chapters and sections. You can’t have one memory called to the front of your mind and expect all the others to remain buried in the oblivion of time.

I looked up again. Bede had mistaken two words close to the end of a sentence. There was an arguable ambiguity about this particular

clausula

, but I took the opportunity to remind him about quantitative prose rhythms that we moderns don’t always hear.

‘It is as you say, Master,’ said Bede with downcast eyes. ‘Forgive my slip.’

‘It is a pardonable error, my child,’ I said. ‘You will be aware that words are important – their choice and meaning can turn the world from its expected course. Pray continue, however, with explaining the double accusative construction.’

Bede was still looking down. ‘Is it true, Master,’ he asked, lapsing into English, ‘that you will be leaving us?’

For the first time, I smiled. I’d seen him yesterday with the other boys and the monks, looking anxiously in through the open doors and windows of the great hall. As discussions had been in Greek, no one could have known about the Emperor’s pardon – witnessed by the Patriarch himself – or about the restoration of my property and status. But the shortest overland distance from Constantinople to Jarrow is two thousand five hundred miles. You don’t have two senators and a bishop turn up with Easter greetings.

They had arrived the day before yesterday. They’d outrun the message of warning Bishop Theodore had sent out from Canterbury, and had caught me as I was finishing Advanced Theology with the novices. No journey is kind on the baggage, and the finery they had taken care to put on before knocking at the gate would have raised eyebrows anywhere east of Ravenna. But in Jarrow it had set the whole monastery and school afire with wonder and with concern.

‘What do you suppose I shall do?’ I asked Bede in Latin.

‘I suppose, Master,’ he replied in a small voice, ‘that you will return to the Great City at the end of the world.’

End of the world! That isn’t how they’d see it back in Constantinople. But I let that pass.

‘Bede,’ I said, still smiling, ‘for all that I have lived in the Empire, and become great in its councils, I was born like you in this land of England. And it is to England that I have returned at the end of my life.’