Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 (19 page)

Read Testament of Youth: An Autobiographical Study of the Years 1900-1925 Online

Authors: Vera Brittain

To be once again at college, hearing the Principal congratulate me with unwonted cordiality upon my ‘brilliant performance’ in getting through Responsions Greek in record time, brought me back with a jerk out of my dream to the realisation that examinations still existed and some people still thought they mattered. So I joined the Pass Mods. class and studied the

Cyropædia

and Livy’s

Wars

with a resentful feeling that there was quite enough war in the world without having to read about it in Latin. My real life was lived in my letters to Roland, which I began to write the next day as soon as I had unpacked.

‘One of the chief joys of college is that the sun sets behind a tall tree opposite my window. I am watching it now and feeling less inclined to make the inevitable plunge into proses and unseens than ever. I feel that with dead yesterday I left reality behind and that unborn to-morrow will only bring concerns of superficial importance. To-day is the aimless intermediate when I cannot think of anything I want to do that is not impossible. I do wonder how I am going to get through this eight weeks.’

In the end it turned out to be a happier term than the one before. I was no longer working alone, and Roland’s letters came even more frequently, in beautiful handwriting on extremely expensive notepaper, which after eighteen years has neither curled nor yellowed. How curious it seems that letters are so much less vulnerable than their writers! His, even at that stage, were invariably punctilious, and the enforced use of two halfpenny stamps instead of a penny one always perturbed him.

One day in the early spring, he and Edward simultaneously wrote in great distress to tell me that Victor, who had become a second-lieutenant in a Royal Sussex regiment, was ill - they feared fatally - with cerebro-spinal meningitis. They both got leave and met in Hove, but they were not allowed to see him. Ultimately he recovered, but with much diminished chances of ever going to the front. For some days I shared their suspense. The love between these three was a genuine emotion which the War had deepened, and I tried to drown my grief for their anxiety in a long discussion into which Norah H. and ‘E. F.’ and Theresa and I, labelling ourselves ‘Young Oxford’, plunged one evening on twentieth-century poetry and the spirit of the age.

We were very much in earnest, and our conclusions, which I wrote down afterwards, may be interesting, for reasons of comparison, to our successors who discuss similar topics, and congratulate themselves on their vast differences from ‘the pre-war girl’:

‘(1) The age is intensely introspective, and the younger generation is beginning to protest that supreme interest in one’s self is not sin or self-conscious weakness or to be overcome, but is the essence of progress.

‘(2) The trend of the age is towards an abandonment of specialisation and the attainment of versatility - a second Renaissance in fact.

‘(3) The age is in great doubt as to what it really wants, but it is abandoning props and using self as the medium of development.

‘(4) The poetry of this age lies in its prose - and in much else that I have no time to put down since it is nearly 2 a.m.’

When my perturbations over Victor were ended, a fresh series arose from the renewal of Roland’s efforts to go to the front. Because of his eyesight, I did not believe that he would succeed, but my cold fear that he might do so made something twist cruelly inside me every time I found a letter from him in my pigeon-hole. He was now stationed at Lowestoft, but seemed to spend more time in the Royal Norfolk and Suffolk Yacht Club writing letters, than in visiting his family.

‘Everything here is always the same,’ he told me on February 25th. ‘The same khaki-clad civilians do the same uninspiring things as complacently as ever. They are still surprised that anyone should be mad enough to want to go from this comfort to an unknown discomfort - to a place where men are and do not merely play at being soldiers. I am writing this in front of an open casement window overlooking the sea. The sky is cloudless, and the russet sails of the fishing smacks flame in the sun. It is summer - but it is not war; and I dare not look at it. It only makes me angry with myself for being here - and with the others for being content to be here. When men whom I have once despised as effeminate are being sent back wounded from the front, when nearly everyone I know is either going or has gone, can I think of this with anything but rage and shame?’

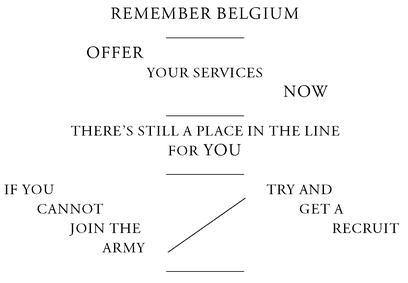

The warm beauty of that early spring, which in France was hastening the preparations for Neuve Chapelle, made me less ready than ever to accept the possibility of his going. I felt, too, vaguely disturbed and irritated by the tranquillity with which elderly Oxford appeared to view the prospect of spring-time death for its young men. The city, like the rest of England, was now plastered with recruiting posters and dons and clerics were still doing their best to justify the War and turn it into England’s Holy Crusade. A pamphlet by Professor Gilbert Murray, called ‘How Can War Ever Be Right?’, had a good sale and was discussed with approval, but the pacifist bias which modified its conclusion that war is occasionally justified was far from appearing in the belligerent utterances of some of his colleagues.

‘I think it is harder now the spring days are beginning to come,’ I wrote in reply to Roland’s letter, ‘to keep the thought of war before one’s mind - especially here, where there is always a kind of dreamy spell which makes one feel that nothing poignant and terrible can ever come near. Winter departs so early here’ (I was comparing Oxford with Buxton, where it lasts until May) ‘and during the calm and beautiful days we have had lately it seems so much more appropriate to imagine that you and Edward are actually here enjoying the spring than to think that before long you may be in the trenches fighting men you do not really hate. In the churches in Oxford, where so many of the congregation are soldiers, we are always having it impressed upon us that “the call of our country is the call of God”. Is it? I wish I could feel sure that it was. At this time of the year it seems that everything ought to be creative, not destructive, and that we should encourage things to live and not die.’

At the end of the term, just when I was least expecting it, the blow descended abruptly. During the last week, I had been really ill with a sharp attack of influenza, which the amenities then obtainable at college were not calculated to cure with exceptional speed. At that time, illness among women students was regarded with surprise, and the provisions made for nursing were somewhat elementary. (It was partly owing to the suggestions of Winifred Holtby and myself at a college meeting after the War that a visiting nurse came to be attached to the Somerville staff.) Except in serious cases, the patient was usually isolated from her friends - who could at least have contributed to her comfort - and left to the care of the domestic staff.

After several days of existing for meal after meal upon the monotonous slops which constituted ‘invalid diet’, and of getting up to wash in a chilly room with a temperature of 103 degrees, I began to feel very weak, and my mother, who was in Folkestone with my father visiting Edward, hurried up to Oxford in alarm. I was thankful to see her, and to be carried off home, three days before the official date for going down, after acting with immense effort the part of the child Victoria in the First Year Play, Stanley Houghton’s

The Dear Departed

.

As my temperature was now normal, and I needed only rest and home amenities to compensate for the depressing after-effects of my illness, my mother left me in Buxton and returned to London to join my father. Lying luxuriously in my comfortable bed after a pleasant breakfast, with a sense of agreeable indifference to Press descriptions of the Allied Fleet in the Dardanelles and the more recent incidents of the new submarine blockade, I lazily opened a letter from Roland which had been forwarded from Somerville. Ten minutes after reading it I was dressed and staggering dizzily but frantically about the room, for it told me that he had successfully manœuvred a transfer to the 7th Worcestershire Regiment and was off to the front in ten days’ time. Assuming that I was going down from Oxford at the official end of term, he had asked me to meet him in London, where he was staying for his final leave, to say good-bye.

As the letter had taken three days to reach me, I fell into a panic of fear that I should miss him altogether. After spending the whole day in writing, telephoning, and tottering down to the town through a sudden spell of bitter cold to send off telegrams, I did endeavour in the few lines that I wrote him that evening to restrain my desperation.

‘I was expecting something like it of course but it is none the less of a shock for all that. It is still difficult to realise that the moment has actually come at last when I shall have no peace of mind any more until the War is over. I cannot pretend any longer that I am glad even for your sake, but I suppose I must try to write as calmly as you do - though if it were my own life that were going to be in danger I think I could face the future with more equanimity.’

My parents returned the next day to find me still feverish and excited. As it would have been ‘incorrect’ for me to go alone to London, and as I was, in any case, still hardly fit to do so, they agreed that Roland, who had telephoned that he could manage it, should come to Buxton for the night. My father, however, did inquire from my mother with well-assumed indignation ‘why on earth Vera was making all this fuss of that youth without a farthing to his name?’

10

When he had driven up in the taxi with me from the station, and we were left together in the morning-room, which looked across the snow-covered town to the sad hills beyond, the sudden effect of seeing him in my semi-invalid weakness after such agitation of mind brought me so near to crying that I couldn’t prevent him from noticing it.

Fighting angrily with the tears, I asked him: ‘Well, are you satisfied at last?’

He replied that he hardly knew. He certainly had no wish to die, and now that he had got what he wanted, a dust-and-ashes feeling had come. He neither hated the Germans nor loved the Belgians; the only possible motive for going was ‘heroism in the abstract’, and that didn’t seem a very logical reason for risking one’s life.

Mournfully we sat there recapitulating the brief and happy past; the future was too uncertain to attract speculation. I had begun, I confessed to him, to pray again, not because I believed that it did any good, but so as to leave no remote possibility unexplored. The War, we decided, came hardest of all upon us who were young. The middle-aged and the old had known their period of joy, whereas upon us catastrophe had descended just in time to deprive us of that youthful happiness to which we had believed ourselves entitled.

‘Sometimes,’ I told him, ‘I’ve wished I’d never met you - that you hadn’t come to take away my impersonal attitude towards the War and make it a cause of suffering to me as it is to thousands of others. But if I could choose not to have met you, I wouldn’t do it - even though my future had always to be darkened by the shadow of death.’

‘Ah, don’t say that!’ he said. ‘Don’t say it will all be spoilt; when I return things may be just the same.’

‘

If

you return,’ I emphasised, determined to face up to things for both of us, and when he insisted: ‘ “When”, not “if ”,’ I said that I didn’t imagine he was going to France without fully realising all that it might involve. He answered gravely that he had thought many times of the issue, but had a settled conviction that he was coming back, though perhaps not quite whole.

‘Would you like me any less if I was, say, minus an arm?’

My reply need not be recorded. It brought the tears so near to the surface again that I picked up the coat which I had thrown off, and abruptly said I would take it upstairs - which I did the more promptly when I suddenly realised that he was nearly crying too.

After tea we walked steeply uphill along the wide road which leads over lonely, undulating moors through Whaley Bridge to Manchester, twenty miles away. This was ‘the long white road’ of Roland’s poems, where nearly a year before we had walked between ‘the grey hills and the heather’, and the plover had cried in the awakening warmth of the spring. There were no plover there that afternoon; heavy snow had fallen, and a rough blizzard drove sleet and rain in our faces.

It was a mournfully appropriate setting for a discussion on death and the alternative between annihilation and an unknown hereafter. We could not honestly admit that we thought we should survive, though we would have given anything in the world to believe in a life to come, but he promised me that if he died in France he would try to come back and tell me that the grave was not the end of our love. As we walked down the hill towards Buxton the snow ceased and the evening light began faintly to shine in the sky, but somehow it only showed us the more clearly how grey and sorrowful the world had become.