Teutonic Knights (37 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

The town of Marienburg temporarily came back into the possession of the order, betrayed by a Bohemian mercenary commander; but it was lost again, after a year’s siege, to hunger. The grand master had no money to hire a relief force, and he had no ships available to carry grain from Livonia to the beleaguered garrison. The revenge of the victors was gruesome and uncommonly severe – execution for the officers of the order’s mercenaries.

Despite these setbacks, both emperor and pope encouraged the order to fight on. Pius II had even used his ecclesiastical weapons against the League and the king of Poland – placing them under the interdict – but to no avail. The Polish king ignored the pope’s demands as complacently as any grand master had ever dared; and the rebellious German nobles and burghers were equally as capable of ignoring papal edicts. The war spread to include all Scandinavia and the Hanseatic cities, to involve Poland and Hussite Bohemia, and the ambitions of the emperor, but in Prussia it remained essentially a civil conflict; Polish troops were often but a minor factor in the warfare. Casimir was unable to raise taxes or call out the general levy without the consent of the diet, and the nobles were reluctant to see the king successful in Prussia. Oleśnicki had returned from the Council of Basel in 1451 to denounce the royal policies. His death in 1455 had not ended clerical opposition to the crown, since Casimir was determined to control the appointment of ecclesiastical officials; in contrast, the churchmen thought that it would be more appropriate for them to appoint the king.

The Lithuanian contribution to the war was to tie down the troops of the Livonian Order. In 1454 the Council of Lords, having negotiated with the Teutonic Knights for an alliance, coerced Casimir into rendering the long-delayed oath to protect Lithuanian rights, then into returning Volhynia to the grand duchy. Afterward they let him fight the war on his own. Casimir could obtain the money to hire mercenaries only by offering concessions to the Polish diet; this was a major step toward establishing the powers of the chamber of deputies as equal to those of the senate (the royal council).

At the end of 1461 the grand master raised a body of mercenaries in Germany which, in spite of its small numbers, seemed capable of sweeping his exhausted enemy from the field. The only major battle of the war resulted, fought in September 1462 between two diminutive forces. The grand master’s army advanced out of Culm, where a base had been established with great effort. The League forces came out of Danzig, the mainstay of the rebel coalition and the only city able to pay any mercenaries. Actually, both armies were ragtag assemblages of city levies, dispossessed farmers, unruly mercenaries, and a handful of knights. The units of the Prussian League proved to be the least weak. Employing the difficult tactic of fighting behind a wagon-fort, they destroyed the grand master’s forces, occupied a number of castles and towns, and threw Erlichshausen back to his last refuges. In the autumn of 1463 the Prussian League’s navy destroyed the order’s fleet.

It was time for peace talks but not yet for a peace agreement; for that both sides had to become even more exhausted. Almost everyone who was anyone offered to mediate the dispute. Pope Paul II and the Hanseatic League made the most determined efforts, and finally, in 1466, a papal legate arranged a settlement. Only repeated reverses and the inability to hire more troops persuaded Erlichshausen to accept the harsh terms.

The peace treaty provided for West Prussia and Culm to be ‘returned’ to the king of Poland and for Ermland to become independent. Marienburg, Elbing, and Christburg also went to Poland. This collection of lands was henceforth known as Royal Prussia. Moreover, the order promised to abandon its ties to the Holy Roman Empire, become a fief of the Polish crown, and accept up to half of its members from Polish subjects. The incompleteness of the victory was a disappointment to those who had hoped to uproot the grand master’s state altogether, but it was a realistic settlement that reflected battle lines that neither side seemed capable of changing significantly no matter how long they fought. Poles could take heart from having at last come into possession of long-disputed territories, and they anticipated that the division of Prussia would leave their ancient enemies too weak to make trouble again. The Prussian League, however, did not see the legal situation in exactly that way: Prussians, even those now under Polish sovereignty, still continued to think of themselves as belonging to one country.

The formal ceremonies disguised all this. Erlichshausen went to Casimir and swore to uphold the peace. Of course, he had no intention of honouring the full terms of the agreement. He did not offer homage as required, arguing that he was restrained by his prior commitments to the pope and the emperor, neither of whom would allow their rights to be infringed in this matter. The papacy quickly supported him in this by declaring the treaty void, a violation of papal charters and harmful to the interests of the Church. The tie of the military order to the papacy again came to supersede secular bonds, to present the Polish king with seemingly insoluble problems in disposing of this troublesome neighbour even after he had won near total military victory. Nor were there any Polish knights who had an interest in joining the Teutonic Order. That provision of the treaty was a dead letter from the beginning.

Despite official rejection of the peace terms, there was nothing to prevent them from being implemented at a later date (homage was finally rendered in 1478, though it was strictly personal, obligating the grand master alone, and not his order or its lands), and certainly there was no reason for the war to begin again. The most important provisions – the territorial concessions to Poland and the independence of the Prussian League – were

fait accompli

. The other provisions were comparatively minor. Casimir had obtained the grand master’s submission once, and that would not be forgotten. The precedent had been set.

The grand master moved his residence to Königsberg, taking the marshal’s quarters. This was accomplished without difficulty since the marshal was in Polish captivity, but there were expensive changes necessary for the castle to serve as the seat of a grand master and his court. Königsberg was not Marienburg, but it was still impressive. Perhaps the change in residence should be seen as symbolic of the grand master’s general loss of status and authority. His castellans and advocates took possession of the most important estates and incomes, leaving him with insufficient income to perform his statutory duties. Power devolved into the hands of the marshal, Heinrich Reuss von Plauen, who was elected grand master in 1469. Plauen was able to continue the reorganisation of the order’s administration for only one year. Upon his death, he was succeeded by a cautious but more traditional grand master, Heinrich Reffle von Richtenberg, whose hope was to restore the prosperity of the land and to end the complicated internal quarrels. However, he could not reach those goals with the slender resources at his command; the selfish interests of the castellans and advocates blocked every effort at reform now and later.

The Thirteen Years’ War had made radical changes in Prussia. By 1466 the estates were no longer complaining about the order’s misrule in matters such as taxation or devaluation of the coinage. Those abuses seemed laughable in retrospect. The noble and burgher estates had won only one significant advantage out of all their struggles – control of their local governments – which they used to suppress the guildsmen and labourers so as to increase their profits to the point that they could pay the few self-imposed taxes and exactions more easily. In East Prussia there was a new land-owning class composed of former mercenaries, who had been paid with fiefs taken from secular knights who had perished and from estates of the Teutonic Order. These mercenaries replaced many of the native knights, and from them descended many of the Junker families of Prussia. Future grand masters would know better than to embark on ambitious projects in support of Livonia or imperial efforts in the Balkans, to challenge the Prussian estates or the king of Poland, or even their own membership. The Teutonic Order was marking time, without even much of an idea of what to do if an opportunity presented itself.

Poland, in contrast, had reached the sea. It had taken lands claimed by the crown since the thirteenth century – Culm, Pomerellia, Danzig – and extended its reach onto lands beyond those: to Stolp and Pomerania. For a short period Casimir had the opportunity to lay a new foundation for royal authority, basing it on the cities and gentry. That policy had achieved military and political victories in Prussia. That he did not extend this to the cities and gentry throughout Poland was a long-term mistake. He had entered into the Thirteen Years’ War against the wishes of the magnates and the Church. (In 1454 Oleśnicki had counselled accepting the concessions the grand master had been willing to make at that time; he had foreseen the stubborn resistance that the well-fortified grand master could offer.) Having achieved peace in Prussia, the king’s interests turned to dynastic politics. To that goal he sacrificed the possibility of internal reforms and his temporary ascendancy over those who would limit royal authority.

For much of the next fifty years the grand masters were impoverished vassals of the Polish kings. Technically their allegiances were divided, but practically there was nothing that they could do. Any effort to change their situation would result in swift cries of outrage from the cities and vassals, opposition from important officers, and rebukes from one or another of their lords. As the fifteenth century came to a close, however, the knights noticed that a number of German princes seemed to have discovered ways to increase their authority over their subjects, foster industry and commerce, and then tax the profits. The knights began to discuss means by which their order might do the same in Prussia. It is worth noting that those same secular reformers were also the swiftest to seize upon the popular demands for reforms in the Church, reforms that ultimately led to the Reformation.

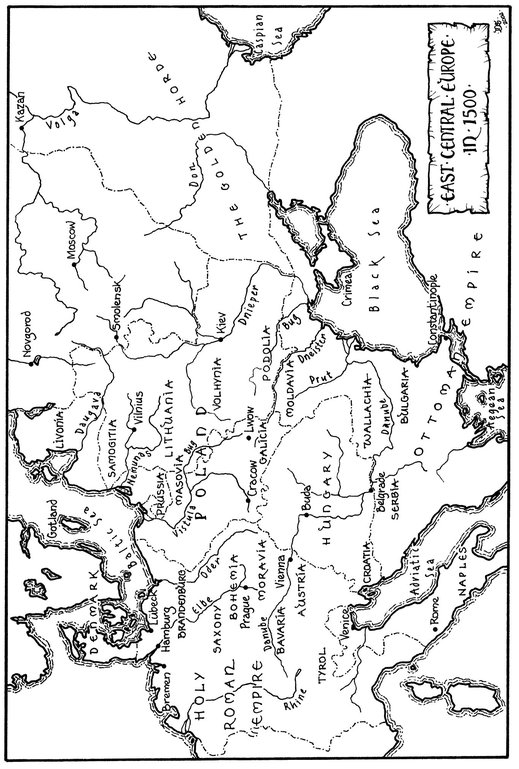

The thunderstorm that the Reformation represented struck Prussia, Lithuania, and Poland one after the other. The Roman Catholic Church in Poland, beset by German demands for reforms, Lithuanian resentment of Polish domination, Uniate desires for more autonomy, Orthodox hatred, and its own parishioners’ fears of each of these foreign peoples, was hard-pressed to find adequate responses. Moreover, the papacy saw East Central Europe as an unimportant backwater, one which could be ignored while the Church concentrated on preserving the physical liberty of the pope in Rome from local families, preventing either Spanish or French domination over Italy, and assisting the Holy Roman emperor in re-establishing the authority of the Church over Lutheran dissidents in Germany. How the papacy could assist the young emperor, Charles V (1519 – 56), in crushing his various enemies – which now included an ever-more aggressive Turkish sultan – without at the same time making him so powerful as to endanger the pope’s own independence was a conundrum which was never resolved satisfactorily. Similarly, it could find no way to help the Polish king until the Counter-Reformation, when the Jesuits came to Cracow and Vilnius.

But this is to move the story along too swiftly. The Reformation did not come all at once, nor did contemporaries instantly recognise in its beginnings what it later became. In East Central Europe as elsewhere the forerunner of the Reformation was the spread of Renaissance culture among the nobility and intellectuals. The centres of the New Latin that marked the adoption of Renaissance ideas and attitudes were always the chanceries – that of the king, first of all, then those of the bishops; and as the model for all, that of the papacy. In Germany the princes vied with proud cities and ambitious prelates in demonstrating their support of the new art, literature, and manners of the Renaissance. Founding and fostering universities was even more irrefutable evidence of intellectual superiority in an age which appreciated the bold façade more than perhaps any other in European history.

Saxony led the way in applying the imaginative yet logical processes of Renaissance thought to government. Humanistically trained scholars, despising the noble-born office-holders and their inefficient ways, proposed to receptive princes ways of centralising authority, raising greater revenues, and encouraging trade and commerce. So successful had the Saxon princes been that the Teutonic Order had elected the physical weakling Friedrich of Saxony as grand master in the hope that he could work the same magic on the economy and government of Prussia.

Friedrich did what he could, which was insufficient to reverse the downward trend of the order’s fortunes, but he did prepare the way for reforms such as those which would be proposed in a few years by a professor at the Saxon university at Wittenberg – Martin Luther. On the whole, however, this grand master’s role was indirect: Friedrich encouraged the bishops to introduce humanists into their cathedral chapters and give them as free a hand as practical to reorganise the administration so as to improve economic and moral life in their dioceses; Friedrich also hired humanists to create an effective bureaucracy on the Saxon model that would permit a more efficient and more just government.

Friedrich’s humanists – first Paul Watt, his former tutor, a professor at Leipzig; and subsequently Dietrich von Werthern, a lawyer – established new offices, thereby eliminating ageing knights from important administrative posts; consolidated convents, appropriating some of their incomes for the grand master’s use; eliminated the practice whereby one estate or the other could veto legislation; redefined court procedure and etiquette; and lastly, in ruthless bureaucratic warfare, drove their conservative enemies from the country. When the German master died, Friedrich’s brother, Duke Georg of Saxony, came up with a plan for dealing with potentially obstructionist successors by abolishing the office. As might have been anticipated, the idea found little support in the Holy Roman Empire. The new German master organised opposition to changes in the traditional practices, and Friedrich’s visits to Germany in 1504 and 1507 led only to a clarification of the issues, not a resolution of them.

Foreign policy was similarly militant. One war scare followed another, with blame for the tensions shared by all sides. The Teutonic Order made no great secret of its ambitions to be freed of all obligations to the Polish crown, to recover its lost territories, and even to become a great power again. In return, the king and his advisors began to discuss means of eliminating the hated order altogether, if possible; at the least to humble its notorious pride. The king, however, was well aware that Duke Georg, whose armies could easily cross Silesia into the Polish heartland, was ready to protect his brother. (Much later Augustus the Strong of Saxony demonstrated the closeness of the two lands.) Furthermore, war in the north of Poland would not go unnoticed by the king’s neighbours. But what really kept the two parties from going beyond burning villages and stealing cattle was the immense cost of warfare. Neither king nor grand master could afford to raise an army; the king could not persuade the diet to levy war taxes, because the representatives did not want royal authority increased, lest he emulate those German lords the Teutonic Order so admired.

The demise of Grand Master Friedrich in late 1510 again presented an opportunity to consider new ideas at the ‘national’ level. One suggestion, made principally by Polish nobles and clerics, was for the election of the Polish king as grand master. They would have welcomed a celibate monarchy, because that would have guaranteed the elective nature of their kingdom. The king, in fact, was willing to consider this proposal for his descendants, provided he could get a papal exemption for himself to marry! The Teutonic Knights, however, had their own candidate already selected: Albrecht of Hohenzollern-Ansbach (1490 – 1568). The family was one of the most important in Germany, but it was hardly wealthy enough to endow eight sons with a suitable living. The order’s interests and the Hohenzollerns’ coincided perfectly.

Obtaining universal approval of the order’s choice was not easy, although the young man was related to the king of Poland and the king of Bohemia and Hungary, and had excellent connections to the Empire and Church. The approval of the convents in Germany and Livonia was obtained – there was no proper election – and in 1511 Albrecht was made a member of the order and installed as grand master on the same day. He immediately received moral and political support from the Emperor Maximilian (1493 – 1519), who urged him to attend the

Reichstag

and other imperial gatherings and, by the way, to give more attention to imperial wishes. In their meeting in Nuremberg in early 1512, Albrecht explained that before he could give his oath to the emperor he had to be freed from his obligations to the king of Poland. Forbidden by the emperor to render homage to the Polish king, he immediately adopted the internal and foreign policies of his predecessor – to reverse the provisions of the two treaties of Thorn by any means possible – but he introduced an entirely different personal life style.

Albrecht had been forthright about his lack of interest in a life without sex, but the members had hastily explained that while ordinary knights and priests had to follow the rules carefully, the grand master was a prominent noble and high official who was exempt from petty requirements. All that he had to sacrifice was marriage, they said, since the vow was celibacy, not chastity. Surely, if popes could live openly with their women, and cardinals and archbishops flaunt their mistresses in public, a great German prince, twenty-one years of age and reared for a secular life, could be excused for not playing the role of a lowly friar?

Albrecht saw more clearly than many of his contemporaries that the future belonged to those princes who could take control of their territories, suppress contentious nobles and unco-operative assemblies, encourage trade and industry, tax the increased prosperity of their subjects, and then hire professional armies for a rational yet daring foreign policy that could take advantage of opportunities when they appeared. He was, in short, among the first of the absolutist princes, more able to exploit his opportunities because the Teutonic Order had already made discipline and order a state tradition – at least, it honoured discipline and order, though those ideals had fallen low since the glorious days of the fourteenth century; although recent grand masters had reduced the strife inside the membership and reasserted control over their officers, they had lacked the means to do more than stage impressive parades and public ceremonies of a mixed ecclesiastical and chivalric nature. Without question, the elaborate costumes of the officers and knights, the bishops and their canons, the abbots with their friars and monks, the burghers with their guilds, and the mounted knights with their troops, made for first-class spectacle. But there was a difference between spectacle and power, and what separated Albrecht from many contemporaries is that, as time passed, he learned how to discern the difference.

The young prince’s plans involved great patience, first to make the necessary reforms so as to increase his power, and second to await the opportunities to exercise this power. At first he relied on the ‘Iron Bishop’ of Pomesania, Hiob, one of the great humanists of the era, whose respect for tradition and moderation was not lost on the Polish monarch and his prelates. In 1515, however, Albrecht came under the influence of Dietrich von Schönberg, a charismatic young charlatan who specialised in mathematics, astronomy, and astrology. The young grand master, always alert to the latest cultural trends, became an enthusiastic listener to his favourite’s astrological predictions. He also became Schönberg’s companion on immoral nocturnal adventures. Freed finally from the company of priests and elderly pious knights, Albrecht proved himself an accomplished student of libertine life, at least of such as Königsberg had to offer. Schönberg also persuaded him that the time had arrived to interject himself into foreign affairs, to use Prussia’s strategic position in the rear of Lithuania now that the Polish monarch, Sigismund I (1506 – 48), was about to go to war with Basil III (1505 – 33) of Russia. Schönberg travelled to Moscow, returning with a treaty promising financial support for an army sufficient in size to tie down Polish troops or even inflict devastating defeats on them; Schönberg then used his considerable rhetorical skills to confuse the Prussian assembly and whip up a war fever among the representatives – he outlined in graphic detail Polish plans (mostly fictitious, the rest exaggerated, but with just enough truth to be plausible) to require that half the knights in the order be Poles and to introduce a tyrannical government on the Polish model, with the inevitable result of seeing poverty and serfdom spread into the yet relatively prosperous provinces of Prussia. The townspeople and knights of Prussia were not complete fools, but their knowledge of the damage that Polish nobles and prelates were doing to their country made them susceptible to the grossest propaganda and racial prejudice.

Such activities could not be kept secret from King Sigismund, nor did Albrecht want them to be. Only when universally recognised as the man who could tip the balance between the great powers could Albrecht make the kind of demands that would restore to his order the lands and authority it had possessed eleven decades earlier. That obviously required a different kind of ruler than those whose piety and loyalty had led them to obey orders from past Holy Roman emperors which had led the military order into one disaster after another. Albrecht was probably not more intelligent than his predecessors; he may not even have been more devious; certainly he did not work harder, at least not when he was young. What he had was a kind of presence, an understanding that he stood above tradition and customary rules. His knights were awed by his birth and breeding – that finely developed air of authority, the assumption that one has the right to make judgements and give orders, and the posture and tone of voice that make inferiors aware that they are in the presence of one of their betters. Certainly no previous grand master would have considered holding a tournament, much less participated in it personally, but Albrecht staged one in Königsberg in 1518 and not only jousted but joined in the melee.

While the adventurous policies of the new grand master made him important in the considerations of high diplomacy, it was an impractical programme. As long as there was no war, Albrecht could strut about as a great figure, impressing the German master with his plans and plans for plans; but when it actually came to war between Poland-Lithuania and Moscow in 1519, he learned that the promised Russian subsidies would not come and therefore he could not pay his troops. Imperial help was likewise absent; Maximilian was rather more interested in Polish help for his own ventures than in rescuing the grand master. As a result of Albrecht’s political miscalculations, every effort to escape from his problems made his situation more precarious. Königsberg’s fortifications indeed repelled the Polish assaults at the last minute, and much of the ground lost in the opening months of the war was recovered, but all his hopes rested ultimately on a great army raised by the German master and brought to the frontier. Eighteen hundred horsemen and 8,000 foot soldiers passed through Brandenburg to Danzig. There, however, the mercenaries waited in vain for the grand master and his money. Albrecht was unable to appear: Polish garrisons blocked the crossings of the Vistula, and Danzig warships patrolled the seas; moreover, he had too little money to pay the army. Ultimately, the mercenaries went home, undoubtedly spreading the word about the grand master’s unreliability as a paymaster.