The 9/11 Wars (2 page)

Authors: Jason Burke

Tags: #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

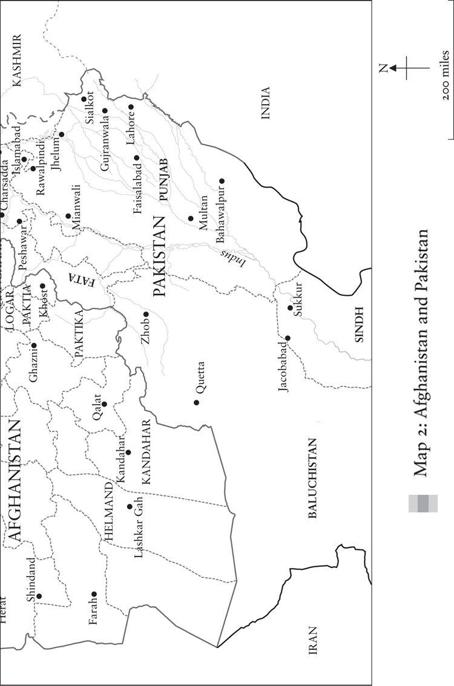

MAP 3

Map 3: Pakistan Tribal Areas

Introduction

If you had looked down through binoculars on to the battered runway of Bagram in the summer of 1998 from frontline Taliban positions on the heights overlooking the Shomali plains, 30 miles north of Kabul, you would have seen little that indicated the role the old Soviet-built airbase could possibly play over the coming years. Through the dust and haze, you would have made out a cluster of ruined buildings surrounded by broad zones of overgrown land strewn with rusting metal stakes, a single battered jeep and no actual aircraft at all on the scarred strip of concrete shimmering in the Afghan sun. The group of scruffy Taliban fighters in filthy clothes who manned the makeshift trenches on the heights would probably have served grapes and tea to you as they did to the rare reporters who wandered up to the frontline in the dead years when no one was interested very much in an intractable and incomprehensible civil war in a far-off land. Occasionally, the fighters fired a rusty artillery piece in the general direction of the airstrip and of their enemies, usually hitting neither.

If you had come back four years later, say in the spring of 2002, you would have seen a startling difference. With the Taliban apparently defeated and dispersed, a bright new era for Afghanistan seemed to be dawning. The once-ruined airstrip down on the plains had become the fulcrum of a build-up of American and other international forces in the country that would continue inexorably over the next years. The bulldozers, the tents going up in the sand and the jets and helicopters lined up in serried ranks on the newly surfaced runway gave a sense that something extraordinary was happening, something of genuine historical importance. The only problem was that the exact nature of its importance was still very unclear. Now, many years on, though much inevitably remains obscured by the immediacy of events, something of that nature has become clearer. The form and the flow of events are beginning to emerge from the chaos of war. This book is an attempt to describe them and through describing them to make sense of them. Bagram is now a small town of around 10,000 people, with its own shopping centres, gyms, evening classes, pizza parlour, Burger King, multi-denominational places of worship and mess halls all protected by treble rows of razor wire and electrified fences. The Taliban are in the hills around, though not yet back in their former positions from where they fired their poorly aimed shells and shared their tea and grapes.

As this book is rooted in many years of ground reporting, it has a different perspective from many of the works written about the events of the years since the attacks of September 11, 2001. Its focus is not the decisions taken in Western capitals but the effects of those decisions. Its aim is to suggest a grubby view from below, rather than a lofty view from above. It is primarily about people rather than about power, particularly people for whom life has changed in ways that no one could have predicted a decade ago. Occasionally these changes have been for the better; sometimes it is still too early to tell what they will bring; often these changes have been, savagely and brutally, for the worse. Sometimes these individuals and communities are passive victims. Often they are actors. Either way, they are not those whose decisions and motivations dominate many accounts. It is out of this intricate web of individuals, communities and events, however, that the story of the conflicts which we have watched, been touched by, even participated in directly or indirectly, is inevitably woven.

This account does not pretend to be objective. Though one aim of the book is to provide a historical record, it does not pretend to be comprehensive either. Such a work, even if practically realizable, would probably be unreadable. Too much has happened in too many places to too many people in too complex a way for it to be compressed and explained even in some 500 pages. The path this narrative takes is thus not necessarily the most direct or the most obvious. The places it visits are not always the most central. In journalism, analysis and academia there is a natural trend to the general, the global and the aggregated. The complex and often messy reality of history as it happens is reduced to single explanations or overarching theories. Though without synthesis nothing is comprehensible, there is a risk that, in reducing the complexity to find an answer, that answer is wrong. The devil is very often in the detail. Much of this book is devoted to exploring this detail.

The dangers of relying on broad generalizations or analyses that ignore the specificities of place, history, personality, culture and identity is very evident in the pages that follow. One early and costly error was a fundamental failure to properly understand the phenomenon of ‘al-Qaeda’. This took years to right. A broader mistake which also proved tragically expensive in lives and resources was the insistence that the violence suddenly sweeping two, even three, continents was the product of a single, unitary conflict pitting good against evil, the West against Islam, the modern against the retrograde. For the last decade has not seen one conflict but many. Inevitably, a multi-polar, multifaceted, chaotic world without overarching ideological narratives generates conflicts in its own image. The events described in this book can only be understood as part of a matrix of ongoing, overlaid, interlinked and overlapping conflicts, some of which ended during the ten years since 9/11 and some of which started; some of which worsened and some of which died away; some of which have roots going back decades if not centuries and some of which are relatively recent in origin.

This is not a unique characteristic of the current crisis but is certainly one of its essential distinguishing qualities.

1

The wars that make up this most recent conflict span the globe geographically – from Indonesia in the east to the Atlantic-Mediterranean coastline in the west, from south-west China to south-west Spain, from small-town America to small-town Pakistan – as well as culturally, politically and ideologically. With no obvious starting point and no obvious end, with no sense of what might constitute victory or defeat, their chronological span is impossible to determine. No soldiers at the battle of Castillon in 1453 knew they were fighting in the last major engagement of the Hundred Years War. No one fighting at Waterloo could have known they were taking part in what turned out to be the ultimate confrontation of the Napoleonic Wars. The First World War was the Great War until the Second World War came along. Inevitably perhaps, this present conflict is currently without a name. In decades or centuries to come historians will no doubt find one – or several, as is usually the case. In the interim, given the one event that, in the Western public consciousness at least, saw hostilities commence, ‘the 9/11 Wars’ seems an apt working title for a conflict in progress.

Another major theme running through this work is inevitably that of religious extremism. What motivates the militants? How are they radicalized and mobilized? Why do they and how can they commit such terrible acts? The answer, as this narrative seeks to make clear, does not appear to lie in poverty, insanity or innate evil. Nor does it lie in Islam, though Islam, like all great religions, has a wide range of resources within it that can be deployed for a variety of functions including encouraging or legitimizing violence. The problem is not Islam but a particularly complex fusion of the secular and the religious that is extremely difficult to counter. The critical question is why this ideology, itself continually evolving, appeals to any given individual or community at a given moment. The answer, as one would expect, varies hugely over time and space. All ideologies are rooted in a context, and radical Islamic militancy is no different. These contexts inevitably change, and charting those shifts is one of the aims of this book.

Looking at violence leads into other major themes. It is now a commonplace to say that recent years have seen a hardening of identities based around ethnic, faith or other communities in response to the supposed ‘flattening’ of local difference by a process of globalization based in a heavily European or American market capitalist system. This is undoubtedly the case and has been consistently underestimated by policy-makers in London and Washington, who remain convinced of the universal attraction of the liberal democratic, liberal economic model in spite of much evidence to the contrary. But a key element missed by many analyses is the degree to which radical Islam is in itself as hostile to local specificity as anything that has come out of the West. One major current running through the pages that follow is the constant tug of war between ‘the global’ and ‘the local’, the general and the particular, the ideological and the individual. It is this tension that has defined much of the form and the course of the 9/11 Wars. The conflict was launched in the name of global ideologies. It was the rejection of global ideologies by key Muslim populations in the middle years of the decade that changed the course of the conflict. Ironically after years of vaunting the merits of the global, the West’s greatest ally at a critical moment was its opposite: bloody-minded local particularism. The same force was also to work in less favourable ways elsewhere however.

This book ends with an account of the more recent phases of the conflict, where, even if cause for great concern still exists, the more apocalyptic predictions of a decade or so ago remain unfulfilled. This relative stabilization of the situation is precarious, however. Only a close examination of the previous course of ‘the 9/11 Wars’ and their antecedents can tell us whether what we are currently witnessing is simply a pause before a new cycle of violence or the uncertain early days of a definitive and positive trend towards something that resembles peace.

This book remains, however, primarily a work of journalism and not of history. It aims, in the long tradition of reportage, to reveal and communicate something about the world and about key events through the voices and views of those who participate in them and are affected by them. Its main aim is to provoke and inform discussion of vital questions rather than confidently lay out certitudes. As new material becomes available, others will improve the accounts of many of the events contained in the pages that follow. Overall I have tried to catch something of the nature of the conflict that has gripped and affected billions of people in recent years. Watching the aerial bombing of Tora Bora in the mountains of eastern Afghanistan in December 2001, with vapour trails from B-52s slicing across the pale sky above the snowy peaks and row upon row of rocky ridges successively lit by the slanting rising sun, a fellow journalist commented as a scene of untold horror and violence and extraordinary aesthetic beauty unfolded before us that only a vast novel really could make sense of what was happening. He was probably right.

PART ONE

Afghanistan, America, Al-Qaeda: 2001–3

1

The Buddhas