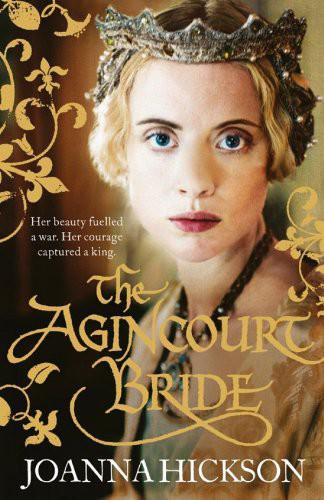

The Agincourt Bride

The Agincourt Bride

For Ian and Barley – the two who share my life, thank goodness.

“It is written in the stars that I and my heirs shall rule France and yours shall rule England.

Our nations shall never live in peace. You and Henry have done this.”

Charles, Dauphin of France

Table of Contents

January 1439

Respected reader,

Before we embark on this story together, I think I should explain that I am not a historian or a chronicler or indeed any kind of scholar. I did not even read Latin until my dear and present husband undertook to teach me on dark winter nights by the fire in our London house, when a more dutiful goodwife would have been doing her embroidery. Luckily my days of being dutiful are behind me. I am now fifty-two years of age and I have had quite enough of stitching and scrubbing and answering becks and calls. I have been a servant and I have been a courtier and now I am neither so I have become a scribe, for one good reason; to tell the story of a brave and beautiful princess who wanted the impossible – to be happy. Of course, here at the start of the tale, I am not going to tell you whether she succeeded but I can tell you that some momentous events, scurrilous intrigues and monstrously evil acts conspired to prevent it.

Two things encouraged me to write this story. The first was those Latin lessons, for they enabled me to read the second, which was a cache of letters found when I used a key entrusted to me for safekeeping by my beloved mistress, the aforementioned princess, to open a secret compartment in the gift she bequeathed to me on her untimely death. These were confidential letters, written at turbulent times in her life, and she was never able to send them to their intended recipients. But they filled gaps in my knowledge and shed light on her character and the reasons she chose the paths she followed.

Sadly, for the most part, she was powerless to shape the direction of her own life, however hard she tried. But there were one or two occasions when she, and I too by extraordinary circumstance, managed to steer the course of events in a direction favourable to us both, although this was never recorded in the chronicles of history.

I do not have much time for chroniclers anyway. They invariably have a hidden agenda, observing events from one side only, and even then you cannot trust them to get a story right. Some are no better than the ink-slingers who nail their pamphlets to St Paul’s Cross. One of them got my name wrong when he recorded the list of my mistress’ companions back in the days of Good King Harry. ‘Guillemot’ he called me, if you can believe it! Who but a short-sighted, misogynistic monk would saddle a woman with the same name as an ugly black auk-bird? But there it is, in indelible ink, and it will probably endure into history. I beg you, respected reader, do not fall into the trap of believing all you read in chronicles, for my name is not Guillemot. What it is you will discover in the story I am about to tell …

Hôtel de St Pol, Paris

The Court of the Mad King

1401–5

I

t was a magnificent birth.

A magnificent, gilded, cushioned-in-swansdown birth which was the talk of the town; for the life and style of Queen Isabeau were discussed and dissected in every Paris marketplace – her fabulous gowns, her glittering jewels, her grand entertainments and above all the fact that she rarely paid what she owed for any of them. The fountain gossips deplored her notorious self-indulgence and knew that, like the arrival of all her other babies, the birth of her tenth child would be a glittering, gem-studded occasion illuminated by blazing chandeliers and that they would effectively be funding it. Paris was a city of merchants and craftsmen who relied on the royals and nobles to spend their money on beautiful clothes and artefacts and when they did not pay their bills, people starved and ferment festered. Not that the queen spared a moment’s thought for any of that, probably.

For my own part, when I heard the details of her lying-in, I thought the whole process sounded horrible. It’s one thing to give birth on a gilded bed but at such a time who would want a bunch of bearded, fur-trimmed worthies peering down and making whispered comments on every gasp and groan? With the notable exception of the king, it seemed that half the court was present; the Grand Master of the Royal Household, the Chancellor of the Treasury and a posse of barons and bishops. All the queen’s ladies attended and, for some arcane reason, the Presidents of the Court of Justice, the Privy Council and the University. I do not know how the queen felt about it, but from the poor infant’s point of view it must have been like starting life on a busy stall in a crowded market place.

Being born in a feather bed was the last the poor babe knew of luxury though, or of a mother’s touch. I can vouch for that. In the fourteen years of her marriage to King Charles the Sixth of France, Queen Isabeau had already popped out four boys and five girls like seeds from a pod, which was about the level of her maternal interest in them. It was questionable whether she even knew how many of them still lived.

Once all the worthies had verified that the new arrival was genuinely fresh-sprung from the royal loins and noted that it was regrettably another girl, the poor little scrap was whisked away to the nursery to be trussed up in those tight linen bands the English call swaddling. So when I first clapped eyes on her she looked like an angry parcel, screaming fit to burst.

I did not take to her at first and who could blame me? It was hard being presented with all that squalling evidence of life, when only a few hours ago my own newborn babe had died before I was even able to hold him.

‘You must be brave, little one,

’

my mother said, her voice hoarse with grief as she wrapped the tiny blue corpse of my firstborn son in her best linen napkin. ‘Save your tears for the living and your love for the good God.’

Kindly meant words that were impossible to heed, for my world had turned dark and formless and all I could do was weep, great hiccoughing sobs that threatened to snatch the breath from my body. In truth I wasn’t weeping for my dead son, I was weeping for myself, swamped with guilt and self-loathing and convinced that my existence was pointless if I could not produce a living child. In my grief, God forgive me, I had forgotten that it was He who gives life and He who takes it away. I only knew that my arms ached for my belly’s burden and desolation flowed from me like the Seine in spate. So too, in due course, did my milk – sad, useless gouts of it, oozing from my nipples and soaking my chemise, making the cloth cling to my pathetic swollen breasts. Ma brought linen strips and tried to bind them to make it stop but it hurt like devil’s fire and I pushed her away. And so it was that my whole life changed.

But I am getting ahead of myself.

I have to confess that my baby was a mistake. We all make them, don’t we? I’m not wicked through and through or anything. I just fell for a handsome, laughing boy and let him under my skirt. He did not force me – far from it. He was a groom in the palace stables and I enjoyed our romps in the hayloft as much as he did. Priests go on about carnal sin and eternal damnation, but they do not understand about being young and living for the day.

I am not pretending I was ever beautiful but at fourteen I was not bad looking – brown haired, rosy-cheeked and merry-eyed. A bit plump maybe – or well-covered as my father used to say, God bless him – but that is what a lot of men like, especially if they are strong and muscular, like my Jean-Michel. When we tumbled together in the hay he did not want to think that I might break beneath him. As for me, I did not think much at all. I was intoxicated by his deep voice, dark, twinkling eyes and hot, thrilling kisses.

I used to go and meet him at dusk, while my parents were busy in the bake-house, pulling pies out of the oven. When all the fuss about ‘sinful fornication’ had died down, Jean-Michel joked that while they were pulling them out he was putting one in!

I should explain that I am a baker’s daughter. My name is Guillaumette Dupain. Yes, it does mean ‘of bread’. I am bred of bread – so what? Actually, my father was not only a baker of bread but a patissier. He made pastries and wafers and beautiful gilded marchpanes and our bake-house was in the centre of Paris at the end of a cobbled lane that ran down beside the Grand Pont. Luckily for us, the smell of baking bread tended to disguise the stench from the nearby tanning factories and the decomposing bodies of executed criminals, which were often hung from the timbers of the bridge above to discourage the rest of us from breaking the law. In line with guild fire-regulations, our brick ovens were built close to the river, well away from our wooden house and those of our neighbours. All bakers fear fire and my father often talked about the ‘great conflagration’ before I was born, which almost set the whole city ablaze.

He worked hard and drove his apprentices hard also. He had two – stupid lads I thought them because they could not write or reckon. I could do both, because my mother could and she had taught me – it was good for business. All day the men prepared loaves, pies and pastries at the back of the house while we sold them from the front, took orders and kept tallies. When the baking was finished, for half a sou my father would let the local goodwives put their own pies in the ovens while some heat still remained. Many bakers refused to do this, saying they were too busy mixing the next day’s dough, but my father was a kind soul and would not even take the halfpenny if he knew a family was on hard times. ‘Soft-hearted fool!’ my mother chided, hiding a fond smile.