The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (21 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

Nothing was left to chance by the Torch planners in Washington. A hundred miles inland, engineer soldiers practiced—often against a stopwatch— loading everything from cans of vegetables to thirty-ton tanks onto every type of freight car existing in America.

Even if saboteurs, secret Nazi weapons, or acts of God should destroy three-fourths of the bridges in the eastern United States, invasion troops and supplies would be transported from the interior to Hampton Roads by preselected alternative routes.

One of the last projects for the Munitions Building planners was the distribution of some one thousand different types of maps. This task had to be carried out under intensely secret conditions. Officers and enlisted men taking part were given no leaves and were more or less under arrest. Maps were shipped to warehouses near Hampton Roads. Watched closely by armed military police, GIs packed the maps into containers for distribution to the proper invasion units, each one having a code marking: 12-R, 8-T, 106-W, and the like.

1

Patton Calls on the President

C

OMMANDING THE WESTERN TASK FORCE

in Operation Torch, America’s first major offensive since the Argonne Forest in World War I, was Major General George S. Patton Jr. Tall, ramrod straight, the fifty-six-year-old Californian was flamboyant in his personal lifestyle, independently wealthy, and possessor of a blue vocabulary that was second to none in the U.S. Army.

The silver-haired Patton had been one of the Army’s best-known figures since his days at West Point, where he had been a center of conversation among cadets after he had stood up between targets as his comrades blasted away on the rifle range. “Wanted to know what it feels like to be under fire,” young George explained.

Weapons Mysteriously Vanish

105

Just prior to World War I, Patton had accompanied General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing into Mexico, where the lieutenant expanded his renown by tracking down a notorious Mexican outlaw, killing the bandit in a two-man shootout, and bringing the corpse back to camp strapped over the front fender of an automobile.

In World War I, Patton’s Army-wide reputation as a bold fighting man gained further luster. He led a tank brigade in several bloody battles, during which he was wounded.

Now, twenty-four years later, General Patton was preparing to go to war again. Eager to fight but a realist, he scrawled in his diary: “[Torch] will be as desperate a venture as has ever been undertaken by any force in the world’s history.”

On October 20, three days before the Western Task Force was to sail for Africa, Patton wrote a letter to his wife Beatrice with instructions that it was to be opened “only when and if I am definitely reported dead.” To his brother-inlaw, Frederick Ayer, the general asked him to “take care of my wife and children should anything happen to me.”

Outwardly, Patton was his customarily upbeat self. When he informed Beatrice that he had been invited to make a farewell call on Franklin Roosevelt in the White House, she admonished her husband to remember he was in the presence of the president of the United States and to be careful not to use profanity.

During his visit to Roosevelt in the Oval Office, Patton was at his fire-eating best, but he managed to keep any blue words out of his conversation. However, when taking his leave, the general reassured the president: “Sir, all I want to tell you is this—I will leave the goddamned beaches either a conquering son of a bitch or a corpse!”

2

Weapons Mysteriously Vanish

D

DAY FOR OPERATION TORCH

was set for November 8, 1942. At his headquarters in Norfolk House in England, forty-six-year-old Major General Mark

W. Clark was deeply worried. His responsibility was coordinating the three task forces that would invade French Northwest Africa, and he was confronted by a monumental problem that threatened to disrupt, or even cancel Torch. Supplies—mountains of them—were mysteriously failing to arrive in England, Torch’s main staging base, from New York City.

Entire shiploads of guns, ammunition, spare parts, and other crucial items were simply vanishing. As time neared for the invasion, General Clark learned that one of his assault divisions in England had not received all of its assigned weapons. Frantic investigation disclosed that the weapons were still sitting on New York City docks. Someone had altered the markings on the crates. It was clear that Nazi spies were stalking New York harbor.

3

A Huge Bounty on Hitler’s Head

I

N MID-NOVEMBER 1942,

soon after American and British forces had stormed ashore in French Northwest Africa, Samuel Harden Church, a wealthy American businessman, was convinced that he knew the key to ending the war in Europe and the Mediterranean. He widely publicized the fact that he would pay a $1 million reward (equivalent to some $12 million in the year 2002) for the capture of Adolf Hitler.

It was specified that the führer had to be taken alive and unharmed. Then the German warlord would be turned over for trial to the League of Nations, an international association of countries, founded after World War I to assure that there would be no future armed conflicts.

Sam Church’s brainstorm died when he did in 1943—with Adolf Hitler alive and well in Berlin.

4

A Tempest in a Teapot

J

UST BEFORE CHRISTMAS

in 1942, hawkeyed newsmen in Des Moines, Iowa, discovered that Amber D’Georg, a striptease artist in a burlesque show, was actually Kathryn Doris Gregory, who was a WAAC and absent without leave from her camp at Fort Worth, Texas. A tempest in a teapot erupted. Across home-front America, the focus on the war was momentarily set aside while citizens paused to savor the “scandal.”

Private Gregory was taken into custody by two military policemen, who had conscientiously carried out their duty by ogling the young woman’s nearly nude performance before hauling her away.

While the WAAC was confined to her quarters, groups that were opposed to women being involved in the military had a field day. Some pastors took to the pulpit to complain that the Army was turning WAACs into shameless prostitutes. Others called for the Army to deactivate the WAAC organization and “send the young women home where they belong.”

In the case of Private Kathryn Gregory, the Army followed a similar line of reasoning. She was given a less than honorable discharge, mostly, it was reported, to quell the hubbub and get on with the war.

5

Press Conferences for “Women Only”

E

ARLY IN JANUARY 1943,

First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt pointed out in her syndicated column, “My Day,” that there were more than seven hundred correspondents telling the folks back home what was going on in the war. Nearly all of the reporters, the First Lady huffed, were “pure male.”

Women in Combat Experiment

107

Eleanor backed up her words with actions. Each Monday morning she held a press conference in the White House. As a ploy to impress on media moguls the shortage of women on their staffs, she barred male reporters from her briefings.

Consequently, without fanfare, the wire services, radio networks, magazines, and newspapers quietly beefed up their journalist corps with women.

6

Secret Plan to Draft Females

A

BOUT A YEAR

into America’s involvement in the war, secret discussions were being held in high places in Washington about a manpower shortage in the armed forces. Lieutenant General Brehon B. Somervell, the Army’s supply chief, proposed alleviating the personnel shortfall by drafting 500,000 women each year, using the same selective service apparatus that was bringing men into the armed forces.

Somervell estimated that there were 11 million women available for duty, and he proposed that the Army take 10 percent of them, leaving the remaining pool of females for other essential tasks in and out of the military.

Never had the United States drafted women, and no member of Congress was especially eager to be branded as being in favor of dragooning young women. Behind-the-scenes contacts with leaders in the Senate and House of Representatives convinced Somervell that his revolutionary proposal would be soundly rejected—perhaps unanimously. Women in uniform would continue to be volunteers.

7

Women in Combat Experiment

G

ENERAL GEORGE MARSHALL,

the Army chief of staff, was mulling over casualty reports from around the world in mid-January 1943. It became clear to him that he would have to try to free more men in noncombat roles to fight. So, in great secrecy, he authorized an experiment in which women would be integrated into male antiaircraft-gun crews.

The field test would be conducted at two batteries protecting Washington, a city Army leaders were concerned might be a target of German bombers. Intelligence reports had indicated that the Nazi scientists were developing a long-range bomber that could hit New York, Washington, and other eastern cities.

There was good reason for the supersecrecy of the experiment. Even though women would not be involved in the actual firing of the ack-ack guns, Marshall feared an uproar on the home front should it leak out that females were involved in what might be regarded as a semicombat type of operation.

Apparently the field test was inconclusive. Or perhaps General Marshall had second thoughts. Whatever the case, the experiment was quietly scuttled.

8

Jailbreak for a Boyfriend

I

N EARLY JANUARY 1943,

Ursula Parrott, an established novelist who had been married and divorced five times, managed to get into the news nationwide— but not in praise of her latest book. Rather she had helped her soldier-of-theweek to escape from the Army stockade at Miami Beach, Florida.

After creating a scheme for springing him, Parrott took him home in her car, hid him, then bought civilian clothes for the escapee. The boyfriend tried to get out of the region, was caught, and implicated Parrott.

Before being hauled off to the local pokey, the novelist explained to newsmen: “It was just an impulse.”

A judge hearing her case was not impressed by impulses. She received a year in jail.

9

Megabucks for Jack Benny’s Violin

P

OLICE OFFICERS WERE OUT

in force as thousands of people crowded into Gimbel’s, a large department store in New York City, not for a major sale but to attend a War Bond rally. These government-issued bonds were to help finance the global conflict, whose cost was astronomical. The bonds were to yield 2.9 percent after a ten-year maturity. It was January 27, 1943.

Magnets for the event were items donated by celebrities, including letters written by George Washington and a Bible owned by Thomas Jefferson.

Famed comedian Jack Benny’s violin, a stage prop in countless radio shows, was actually a $75 imitation. Despite it being a fake, Julius Klorfien bought the violin for $1 million (equivalent to some $12 million in the year 2002).

Countless people around the United States were flabbergasted, not only by the fact that a fake musical instrument had been bought for such an outrageous sum, but who in Hades was Julius Klorfien? Few Americans had ever heard of him. He turned out to be the owner of a thriving tobacco business, Garcia Grande cigars.

10

“Mom, Keep Your Chin Up!”

A

LLETA SULLIVAN WAS A TYPICAL

American mother with sons in the service. In her bedroom at the family home on Adams Street in Waterloo, Iowa, she

“Mom, Keep Your Chin Up!”

109

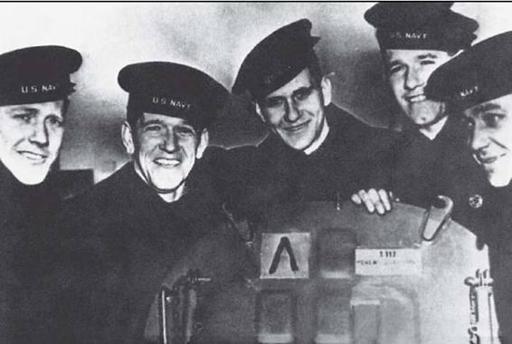

The deaths of the five Sullivan brothers rocked home-front America. From the left: Joe, Frank, Al, Matt, and George. (National Archives)