The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (3 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

Near Topeka, Kansas, word was received by a group of the State Field Dog Trials. One man voiced the sentiment of all: “I guess our hunting will be confined to those goddamn Jap bastards from now on!”

In New Orleans, some four hundred grim citizens stood in front of the Japanese consulate and watched officials there burning papers in the courtyard. A stiff breeze caused papers to float up at times while they were still burning. The Japanese chased them about the yard. Like fans at a football game, the Americans roundly hissed and booed each chase.

A fire engine rushed to the Japanese consulate in San Francisco when the diplomats had been so rapidly burning documents that they set the building afire.

Members of a labor union in Chattanooga, Tennessee, unanimously voted its own declaration of war against the Japanese Empire, and those in the Rotary Club in Kodiak, Alaska, pledged to let their beards grow until Japan was whipped.

Arthur A. Names, a man who had flown in France in World War I, sent a message to the White House, in Washington, offering to become what later would be known to the Japanese as a kamikaze. “I will personally fly a plane

5

A few days before Pearl Harbor, a newspaper published Washington’s supersecret plan for defending against any attack. The information had been stolen by a mole in the War Department. (Chicago Tribune)

load of explosives against any enemy battleships wherever and whenever the [president] may deem it necessary and expedient.”

There were exceptions to the instant belligerence. Ernest Vogt and his family were eating a late chicken dinner at their home in New York City when they heard a radio report. Vogt was skeptical: “I think it’s another Orson Welles hoax.”

Back on October 30, 1938, twenty-three-year-old Orson Welles presented a radio play, Invasion from Mars. To make the fantasy seem credible the script simulated newscasts announcing that forces from Mars had landed in New Jersey, were heading across the Hudson River to New York City, and were devastating the region with death rays. It was brilliant radio—and America panicked. It was several days before the last visages of terror had vanished.

As the Pearl Harbor bulletins began to saturate the air almost continually, panic struck. That night at a military post a nervous sentry challenged three times, received no answer, and shot an army mule.

At Fort Sam Houston in Texas, an obscure brigadier general named Dwight D. Eisenhower got an urgent telephone call from Washington. Wife Mamie heard him say, “Okay, I’ll get there right away.” As he rushed off to catch a plane for Washington, he said he hoped to be back soon. “Soon” would be four years.

In Pittsburgh, Senator Gerald Nye had arrived to address some three thousand members of America First, an isolationist organization whose most prominent figure was Charles A. Lindbergh, the first man to have flown the

Dispute in the President’s Office

7

Atlantic alone. America First had some 100,000 members and claimed that “the warmonger Roosevelt” was taking the nation down a rocky road to war.

Now, just before Senator Nye took to the podium a reporter told him about the attack on Pearl Harbor. Nye snapped: “It sounds terribly fishy to me.”

A few days earlier, Eleanor Roosevelt, the president’s wife, had invited Edward R. Murrow, who had gained world fame while broadcasting back to the United States on short-wave radio the German bomber attacks on London in 1940, and his wife to dinner at the White House on December 7. Now Murrow’s wife telephoned Mrs. Roosevelt: Was the couple still expected for dinner?

“We all have to eat,” the First Lady replied. “So come anyway.” Later that night the president and the radio newscaster were in the White House study. Clearly, Roosevelt was angry. Pounding a table, he described to Murrow how American planes were destroyed “on the ground, by God, on the ground!”

1

Dispute in the President’s Office

L

ATE ON THE NIGHT OF DECEMBER 7

, President Roosevelt went to the Oval Office. At about 10:30

P

.

M

., a procession of grim-faced leaders of the Senate and House filed into the room and took seats. Behind his highly polished desk, Roosevelt gave the lawmakers a briefing on the Pearl Harbor debacle. He pulled no punches.

The group listened in dead silence, clearly astonished that such a disaster would be “allowed” to occur. “The principal defense of this country and the whole West Coast of America has been seriously damaged today,” the president declared. Lawmakers were flabbergasted. What Roosevelt was saying was that a Japanese invasion of California might be forthcoming.

It was an informal gathering. Roosevelt was puffing on his trademark cigarette and long holder. Nearly everyone was casually dressed, having been urgently summoned only an hour or two earlier. Now the president dropped another blockbuster.

“There is a rumor, I don’t know if it’s true, that two of the planes [in the bombing] were seen with [Nazi] swastikas on them,” he said. “I don’t discount German participation in the air strike.”

Senator Thomas T. Connally, chairman of the Foreign Relations Committee, had become steadily more angry during the briefing. It appeared to him that Roosevelt and his armed forces secretaries had cooked up excuses for the catastrophe. Suddenly, Connally called out: “Hell’s fire, didn’t we do anything?”

Roosevelt flushed at this outburst, then replied evenly: “That’s about it.” Connally then turned his guns on Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox, demanding to know, “Well, what in the hell did we do?”

Knox started to sputter a response when the irate Connally interrupted him. “Didn’t you say just two weeks ago that we could lick the Japs in two weeks? Didn’t you say that our Navy was so well prepared and located that the Japs couldn’t hope to hurt us at all?”

Knox appeared shaken and fumbled for a reply. But Connally wasn’t finished. “Why did you have all the ships at Pearl Harbor crowded in the way you did?” he exclaimed. “I am amazed by the attack by Japan, but I am still more astounded at what happened to our Navy. They were all asleep. Where were our patrols?” Knox made no reply.

2

Calls for Retreat to Rockies

T

HE FLOOD OF GLOOMY REPORTS

from Hawaii triggered near hysteria among many of the nation’s best-known leaders. One even telephoned the White House and, almost shouting, declared that the West Coast was not defensible, that Japanese forces would land there soon, and recommended that a battle line be organized in the Rocky Mountains to halt a cross-country Japanese drive to capture Washington.

3

Submarines Off West Coast

A

T THE TIME THE BOMBERS HIT PEARL HARBOR,

the Japanese had nine submarines submerged a short distance off the West Coast of the United States. They were lying in wait from San Diego in the south to Seattle in the north.

The submarine skippers had strict orders not to fire torpedoes or surface until the precise moment the first bombs exploded on Pearl Harbor. Only a few minutes before the deadline, the captain on one underwater craft spotted the freighter Cynthia Olsen in his periscope. The ship was loaded with lumber and bound for Hawaii.

Glancing steadily at his watch, the skipper raised one arm to signal his gunner. Suddenly, he brought the arm down and a torpedo flew out of its hatch. Minutes later the Cynthia Olsen disappeared below the waves—probably the first U.S. ship to be sunk in the open sea.

A few days later the liner Mauna Loa, carrying thousands of Christmas turkeys, sailed for Honolulu. Suddenly, the ship was ordered to return to port. In the haste of making a run for safety with a Japanese submarine on her tail, the Mauna Loa ran aground northwest of the Columbia River. Most of the turkeys washed ashore, providing hundreds of residents of that Oregon region with their Christmas dinners.

At about the same time, the tanker Emido was sailing southward, along the coast from Seattle to San Pedro, California. Off Cape Mendocino, Califor

Roosevelt Rallies the Nation

9

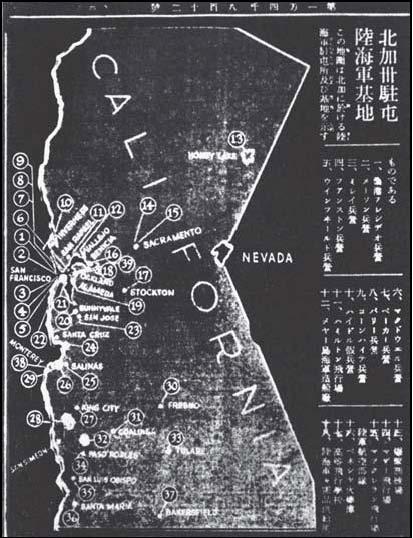

Japanese invasion map of California found on a spy arrested by the FBI. The numbers identify barracks, army posts, naval bases, shipyards, and airfields. (Author’s collection)

nia, a Japanese submarine, probably having exhausted its torpedoes, surfaced and pumped six shells into the unarmed ship. Hastily, the crew abandoned her, but the Emido didn’t sink. Instead, it meandered along the shore aimlessly until it came to rest on a rock pile north of the shelling site. None of these actions on the front doorstep of home-front America became known to the citizens. The Navy kept the Japanese attacks secret.

4

Roosevelt Rallies the Nation

W

ASHINGTON, D.C., WAS GRIPPED BY A BITTER COLD

on the morning of December 8, 1941. Outside the Capitol, squirrels scampered along the leafless tree branches. Inside the building a few minutes after noon, a procession of government leaders walked solemnly down the long corridor in the Capitol and through the broad rotunda. Behind Senate Majority Leader Alben Barkley and Minority Leader Charles McNary, the delegation entered the cavernous chamber of the House of Representatives.

Next came the justices of the Supreme Court in their flowing black robes, and behind them as they took seats down front were hundreds of grim members of the House and Senate. In the front row were silver-haired General George C. Marshall, Army chief of staff; Admiral Harold “Betty” Stark, chief of

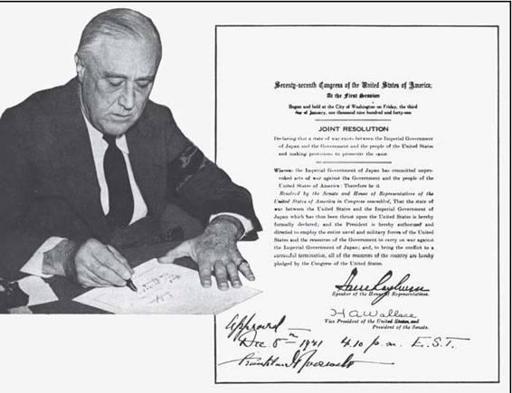

President Franklin Roosevelt signing the joint resolution of Congress declaring war on Japan. (Library of Congress)

Naval Operations; and members of the cabinet. At 12:31

P

.

M

. Speaker of the House Sam Rayburn of Texas rapped his gavel and called out: “The president of the United States!”

There was thunderous applause as Franklin Roosevelt painfully entered the room on the arm of his thirty-four-year-old son, Marine Captain James Roosevelt. Crippled by polio at the age of thirty-nine, the president wore a fifteen-pound brace on each leg.

Struggling up to the podium, the chief executive opened a black loose-leaf notebook. A hush fell over the assembly. He began to read: “Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.”