The Alchemaster's Apprentice (41 page)

Read The Alchemaster's Apprentice Online

Authors: Walter Moers

He heard a low, throaty sound, possibly made by a fat frog. It came from the direction in which his nose was taking him.

You’re feeling terminally sick?

Off to the Toadwoods with you, quick!

The Uggly’s words rang in his ears. Did the Incurables really exist, or were they just another old wives’ tale concocted by grown-ups to dissuade their children from wandering off into the woods?

All alone you there will be,

with no one else around to see.

‘Precisely,’ thought Echo. ‘No one wants to be here, least of all yours truly! Where’s that confounded moss?’ He lifted his little nose and sniffed the air. The scent of Toadmoss was growing stronger. For the first time in his life, he cursed his acute sense of smell for leading him ever deeper into this wilderness.

So dig yourself a grave to fit

and then, my friend, lie down in it.

‘Rhyming is one thing,’ Echo reflected, ‘digging your own grave is quite another.’ What a gruesome thought! Who dreamt up these ideas? Poets were strange creatures. That Knulf Krockenkrampf needed his head examined.

The sun was sinking. Just to make matters worse, the forest was now populated by shadowy figures that stole through the trees and waved to him from the topmost branches. ‘No,’ he told himself bravely, ‘the branches are simply stirring in the evening breeze. There aren’t any shadowy figures. Or Incurables.’ All that was incurable was his own lively imagination.

In the distance he heard again the low, throaty sound. The trees thinned and he eventually came to a narrow path, a beaten track leading in the direction from which the scent of Toadmoss was drifting towards him.

‘Ah, civilisation,’ he thought, feeling relieved. Well, only what might be regarded as civilisation in such surroundings: a boggy path dotted with puddles and stumbling blocks in the shape of tree roots and boulders. Still, no more thistles and stinging nettles. A rough aid to direction, at least. Presumably, this was the path Izanuela herself had taken when gathering Toadmoss.

Echo was further reassured by the protracted drum roll of a wood-pecker. ‘There are only harmless little forest creatures here,’ he told himself. ‘Woodpeckers and frogs, beetles and squirrels.’ He rounded a bend in the path half hidden by the massive root of an oak tree. What awaited him beyond it made his heart stand still for a moment. He stood there transfixed. Seated with its back against the oak tree’s blackened trunk was the skeleton of a man. His white bones had been picked clean by ants and were cocooned in spiders’ webs. Wild ivy was growing around his thigh bones and between his ribs. A red forest rose was flowering on his lower jaw, which had dropped open. Echo fluffed out his tail and hissed.

You’re feeling terminally sick?

Off to the Toadwoods with you, quick!

A butterfly landed on the skull and folded its wings. This had been an Incurable, no doubt about it, but he was dead. ‘It isn’t a pleasant sight,’ thought Echo, ‘but it’s less alarming than being ambushed by someone with an incurable disease.’ The poor man hadn’t even had time to dig himself a grave. Echo’s tail resumed its normal appearance.

All alone you there will be,

with no one else around to see.

Echo found it awful to picture the man dying all by himself in the woods. On the other hand, wasn’t it awful to die anywhere? And wasn’t everyone alone when the time came? He shook off the disagreeable thought and walked on along the path. Really nice of Izanuela to send him blithely off into a wood with a skeleton lurking in it!

A

skeleton? Echo froze once more. Another one was lying a few paces further on. A miaow of alarm escaped his lips, but he didn’t hiss or fluff out his tail. This man’s remains were lying full length in the grass. Busy bees and bumblebees were droning around a whole garden of weeds and wild flowers that had sprouted from between his bones. ‘A peaceful sight, actually,’ Echo thought to himself. Why were people so scared of skeletons? Nothing could do one less harm than a skeleton and in this particular case, dead was really better than alive.

skeleton? Echo froze once more. Another one was lying a few paces further on. A miaow of alarm escaped his lips, but he didn’t hiss or fluff out his tail. This man’s remains were lying full length in the grass. Busy bees and bumblebees were droning around a whole garden of weeds and wild flowers that had sprouted from between his bones. ‘A peaceful sight, actually,’ Echo thought to himself. Why were people so scared of skeletons? Nothing could do one less harm than a skeleton and in this particular case, dead was really better than alive.

He walked on, keeping his eyes peeled so as not to be startled by another dead Incurable. Wisely so, because it wasn’t long before the next one came into view. Like a knight on a medieval tomb, he was lying on a huge boulder with his eye sockets directed at the canopy of foliage overhead and his skeletal arms folded on his chest. Whether or not he hadn’t liked the thought of flowers growing through him, he couldn’t defy the moss, which had spread from the boulder to his bones.

Moss … Of course, thought Echo, that’s why he was here, not to view the Incurables’ mortal remains. He sniffed the air once more. Yes, the smell of Toadmoss was growing steadily stronger.

Again he heard that low, throaty sound issuing from the depths of the forest. No doubt about it: Toadmoss and the author of the sound shared the same location. He walked on along the path, undistracted by the skeletons lying or sitting here and there. One Incurable was staring down at him from his perch in the fork of a large tree; another, who had presumably wanted to cut his sufferings short, was hanging by his neck from a branch.

One part of the forest consisted almost entirely of willow trees whose foliage, which resembled strands of pale-green hair, hung down to the ground. The smell of Toadmoss was now so intense that Echo caught it every time he drew breath. Mingled with it were other smells - unpleasant ones! - that prompted him to slacken his pace. Was that a clearing up ahead?

Although the sun had already set, the sky was still faintly tinged by its afterglow. The moon was three-quarters full. Echo came to a halt. Yes, it was a clearing. More than that, however, it was one of Nature’s marvels.

Jutting from the ground was a forest of tall slabs of stone. What kind of wood was it in which rocks grew instead of trees? It seemed unwise to approach them, but the smell of Toadmoss was coming from their direction. Having come this far, Echo wasn’t about to return without achieving anything.

He ventured a little nearer the slabs, which looked old and weather-worn. Many of them overgrown with creeper, they differed in shape and colour. Some were bigger, some smaller, some paler, some darker, some jet-black, others streaked with red and white veins. One slab was thick and composed of dark-brown porous stone, another was thin, with a white, mirror-smooth surface. Echo now saw that some of the slabs bore inscriptions. No, not just some, many - possibly all of them! This was becoming more and more mysterious. What was written on them?

He took a close look at one of the monoliths. Black marble. An engraved name. A date. Another date. The next bore another name, another date. He began to doubt that the rocks had grown here naturally. They had been embedded in the ground, but by whom? And when? Were they a work of art? A monument? An artefact from another age? He felt ashamed of his naivety in mistaking them for plants.

He read some more inscriptions. They always comprised names and dates. Some of the surnames were familiar to him from Malaisea. Many were emblazoned on the fascia boards of pharmacies and bakeries, opticians’ and butchers’ shops. And then he read one that affected him so deeply that he couldn’t suppress a sob:

FLORIA OF INGOTVILLE

It was the name of his former mistress.

Echo grasped the truth at last: this was a graveyard! He hadn’t recognised it at once because he’d never been to one before, only heard tell of such sinister places. The townsfolk of Malaisea had consigned their burial place to the depths of the forest because they couldn’t endure the sight of it. They were too preoccupied with their ailments to tolerate a perpetual reminder of death, so they came here to bury their nearest and dearest, not to mourn them.

This was the kingdom of death. His late mistress’s mouldering corpse was down below, together with countless others. He now knew where the unpleasant smells were coming from: the ground itself.

He found it only too easy to imagine the dead breaking through the surface, as they had in Ghoolion’s story of the accursed vineyard, and grabbing him with a view to dragging him down into their damp, worm-infested world below ground. He must get out of here fast! He was still on the outskirts of the cemetery; he had only to turn and go.

But he stayed where he was. The smell of Toadmoss was stronger than ever. It was luring him straight into the stone forest.

What should he do? He shuffled irresolutely from paw to paw. Why should that confounded moss be growing in the middle of a cemetery, of all places? Why had that stupid Uggly failed to mention the fact? It wouldn’t have hurt her to give him a little prior warning.

On the other hand, would he have gone at all? Izanuela knew only too well what she was doing and what was better left unsaid. He pulled himself together. She wanted some Toadmoss and Toadmoss she should have. He had no wish to give her the satisfaction of calling him a scaredy-Crat. If she herself had crossed this graveyard unscathed, why shouldn’t he be able to do the same? He set off, heading for the heart of the burial place.

Many of the graves looked very old; others, judging by the look of the soil, had been dug not long ago. Here and there, empty graves without headstones awaited their future occupants. Rainwater had turned one of them into a big puddle whose surface reflected the moon. Echo shivered.

The stench of Toadmoss was now so strong that he must be getting very close. He took another few steps. Sure enough, the penetrating smell was coming from an open grave just ahead of him. He went up to the edge and peered into it.

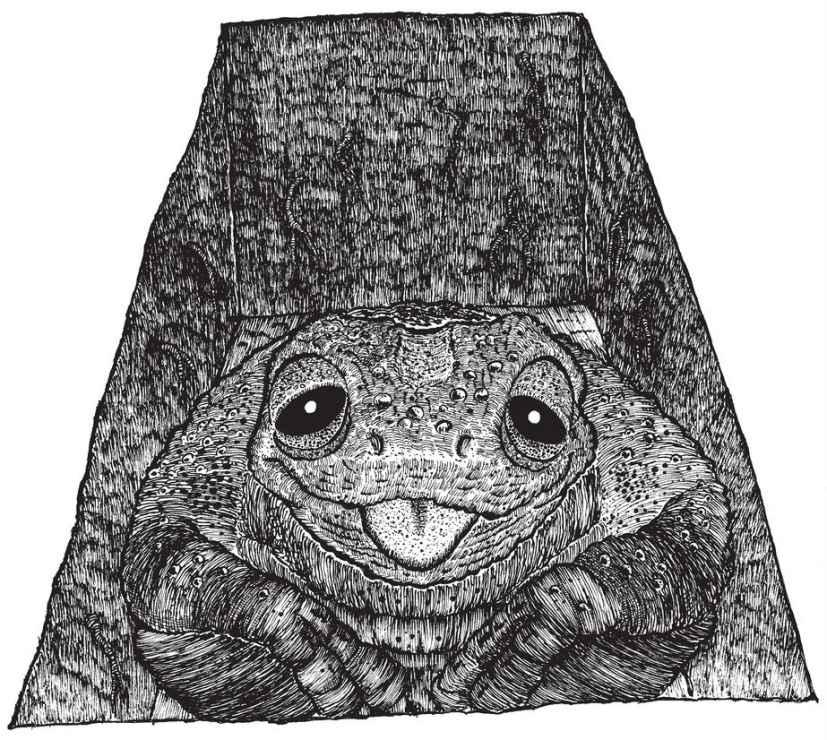

Ensconced in the grave was a gigantic frog. Its dark-green body, which was covered with black warts, was so big that it occupied almost half the pit. Staring up at Echo with turbid yellow eyes, it opened its slimy mouth and uttered the throaty sound he’d already heard more than once.

‘A cat?’ the creature muttered to itself. ‘What’s a cat doing here?’

Echo took advantage of this to strike up a conversation. ‘I’m not a cat,’ he said, ‘I’m a Crat.’

‘You speak my language?’

‘Yes,’ said Echo. ‘My, you’re a frog and a half!’

‘You’re wrong there. I’m not a frog, I’m a toad.’

Echo’s head swam. If this was a toad, there probably wasn’t any Toadmoss here at all. He’d been following the smell of the toad, not the moss. That was logical. What smelt more like a toad than a toad?

‘I’m sorry,’ he said, thoroughly disconcerted. ‘I was looking for some Toadmoss. You smell so much like that plant, I thought -’

‘Wrong again,’ the toad broke in. ‘I don’t smell like Toadmoss, Toadmoss smells like me. There’s a subtle difference. This forest is called the Toadwoods, not the Toadmoss Woods.’

‘You’re right,’ Echo said politely. ‘I made a mistake, as I said.’

‘Wrong yet again. You didn’t.’

‘Didn’t I? How so?’

‘See this green stuff on my back? What do you think it is?’

‘You mean it’s …’

The toad nodded.

‘Toadmoss. The only Toadmoss growing in the Toadwoods.’

Echo didn’t know what to think. On the one hand he had found some Toadmoss at last; on the other it was growing on the back of a monstrous and rather vicious-looking creature residing in a grave. He had hoped to scrape some off a root somewhere, but it now looked as if obtaining the stuff would present certain problems.

‘You’d like some of my moss, is that it?’ asked the toad.

‘Yes indeed!’ said Echo, relieved that the monster had broached the subject itself.

‘No moss would be your loss, eh?’

Echo forced a laugh.

‘Sorry,’ said the toad, ‘I couldn’t resist that. It’s the only joke I know.’

‘That’s quite all right,’ said Echo. ‘I’m afraid it’s only too true. Without your moss I’m completely stumped. It’s a bit difficult to explain, but the long and the short of it is that unless I take some of your moss home I shall lose my life in the very near future.’

Other books

Worth Dying For by Denise, Trin

Silenced by K.N. Lee

A Kind of Magic by Shanna Swendson

Virtually Real by D. S. Whitfield

Full Disclosure by Thirteen

Mourn Not Your Dead by Deborah Crombie

Brink of Chaos by Tim LaHaye

The Sharpest Edge by Stephanie Rowe

A Flower in the Desert by Walter Satterthwait

Deeply Odd by Dean Koontz