The Ancient Alien Question (14 page)

Read The Ancient Alien Question Online

Authors: Philip Coppens

But the best evidence, Sitchin argued, was that the name of Khufu was misspelled—conforming to a notorious misspelling in a book to which Vyse had access. He claims that the inscription reads Ra-ufu, not Khufu. This mistake would have been unthinkable for ancient Egyptian writers to make, but it is explainable if the inscription was done in 1837. That year, an academic book about hieroglyphics called

Materia Hieroglyphica

had been published, in which the name of Khufu was erroneously entered. The lines of the sieve were so close together that they appeared in the print like a massive disc, which is in fact another way of writing “Ra.” It is known that Vyse had this book with him.

Definitely, Vyse had the opportunity to commit this fraud. But in any crime, motive is an important consideration—and Sitchin is able to provide one: Vyse’s expedition was running short of funding, and had not uncovered any major revelation that would grab headlines, which is what he needed to receive more funding. The discovery of the cartouche was therefore a gift from heaven. Too good to be true?

Perhaps. However, it seems that accusations of forgery work both ways. Sitchin’s opponents have pointed out that the visual evidence for the misspelling that Sitchin provides is erroneous at best, and some claim Sitchin has actually forged evidence in support of his conclusions of forgery! His opponents point out that various other photographs, including those circulated by Rainer Stadelmann when he was working on the ventilation system in the Great Pyramid in the 1990s, reveal that the correct sign was used in the writing in the relieving chamber—hence, Ra-ufu is in fact Khufu. In their opinion, Sitchin, not Vyse, is guilty of forgery.

In Sitchin’s possible defense, when he first published his accusation in 1980, several photographs now in existence, including Stadelmann’s, had not yet been made; only drawings existed, and perhaps these showed the inaccuracy as well? Unfortunately for Sitchin, that is not the case: A sketch of the cartouche appears

in Perring’s book, published in 1839. Sitchin gives no precise source from which he got the cartouche, but as Perring is listed in the bibliography, most assume it was his book that provided Sitchin with a drawing of the cartouche. And, as such, the conclusion drawn by those antagonistic towards Sitchin is that he purposefully faked the story of a forgery in an attempt to predate the pyramid to several millennia before Khufu.

The Great Pyramid is also the subject of isolationism: It tends to be seen in isolation. But it is not. The Pyramid of Khafre next to it is almost as big, as is the Red Pyramid at Dashur. If aliens built the Great Pyramid, then it needs to be argued that they were also responsible for at least some of the other pyramids in ancient Egypt.

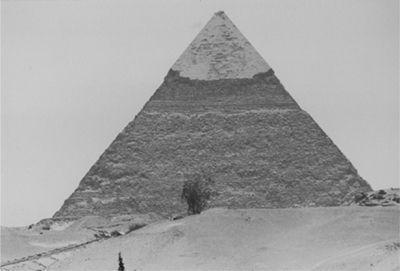

Just slightly smaller than the Great Pyramid, the Pyramid of Khafre has retained some of its cover stones at the very top of the pyramid. It therefore allows one to imagine how brilliant—literally—these pyramds would have looked in their heydays.

So is there no mystery to the Great Pyramid? Actually, there is. The evidence suggests that though Khufu was responsible

for its construction, he had at his disposal technology and information that official archaeology does not credit the Ancient Egyptians with. It is technology that was millennia ahead of its time, helping to build the pyramid with an accuracy that defies modern standards.

The Great Pyramid has been measured in extraordinary detail, which has revealed how purposefully everything to do with this pyramid was executed. Early on, explorer W.M. Flinders Petrie found that the internal volume of the sarcophagus in the King’s Chamber was 1,166.4 liters (about 308 gallons), and the external volume was precisely twice that: 2,332.8 liters (616 gallons). This clearly underlines that whoever built this had access to advanced technology and mathematics. Accurate measurements of the Great Pyramid give its dimensions as 230.2506 meters (755.43 feet) on the North Base, 230.35869 meters (755.77 feet) on the West Base, 230.45318 meters (756.08 feet) on the South Base, and 230.39222 meters (755.88 feet) on the East Base. The maximum deviation from perfect square is therefore 0.09812 meters, or 0.80 feet, which is an accuracy of 0.0004 centimeters per meter, or 0.0015 inch per foot. The deviation from the 90-degree angles of the four corners of the pyramid is 0 degrees 00’02” (northwest), 0 degrees 03’02” (northeast), 0 degrees 3’33” (southeast) and 0 degrees 0’33” (southwest)—an extraordinary accuracy. The slopes of the pyramid are at an angle of 51 degrees, which is known as the “perfect” angle, as it embodies the mathematical ratios of pi and phi—two ratios the ancient Egyptians allegedly did not possess as they were “only” discovered by the Greeks. Yet their usage is on display throughout the pyramid complex. Such accuracy is stunning, far exceeding modern building achievements. No wonder, therefore, that as early as John Taylor in 1859, its construction was ascribed to a divinely inspired race of non-Egyptian invaders, though Mark Lehner in

The Complete Pyramids

(1997) only ventured as far as to question “Why such phenomenal precision?”, arguing that the answer eluded us.

Choosing to remove the responsibility for construction of the Great Pyramid—or any other monument—from the native culture is a dangerous exercise that today will greatly upset the scientific establishment. Indeed, it is clear that, for science, keeping all buildings “native” to the culture in which they are found is far more important than actually going with the available evidence. And in the case of the Great Pyramid, it was its accuracy, which far exceeded the accuracy of other buildings of its time in ancient Egypt, that has prodded so many to conclude it was built by non-Egyptians. But the available evidence actually suggests that Khufu, an Egyptian, did build it, but that somehow he had at his disposal information and building techniques that did not seem to have been used before. That is the true great mystery of the Great Pyramid.

Detail of the section of the Pyramid of Khafre where the Arabs abandoned their work in removing the cover stones. It reveals the extraordinary precision involved in the building work of this and other pyramids.

It is a fact that not a single pyramid has ever been found in which a mummy was present. Egyptologists are quick to point out that grave-robbers are responsible for this, but in truth intact

pyramids

have

been found, and when their sarcophagus was opened, no mummy lay inside. So, if not a tomb, the question is what the pyramid could be. The most vociferous answer in recent years has come from engineer Christopher Dunn, who, in

The Giza Powerplant

, argues that the pyramids are power plants.

Flinders Petrie inspected the King’s Chamber and argued that it had been subject to a violent disturbance, which had shaken it so badly that the entire chamber had expanded by 1 inch. The culprit was identified as an earthquake, the only natural force capable of creating sufficient force. But as Dunn highlights, the King’s Chamber is the

only

room affected by this event; the Queen’s Chamber remained unaffected. Dunn says he has seen no evidence of laser cutting in ancient Egypt, but the rocks display evidence that

some

machinery was used. Flinders Petrie estimated that a pressure of 1 to 2 tons on jewel-tipped bronze saws would have been necessary to cut through the extremely hard granite; Dunn found evidence of lathe turning on a sarcophagus lid in the Cairo Museum. Petrie himself found evidence of spiral drilling in granite, measuring the feed rate as 1 in 60, which is incredible for drilling into a material like granite. Petrie was impressed with this feed rate, as he was confronted with an engineering anomaly. The ancient Egyptians could not have achieved this by using the tools ascribed to them. Dunn’s analysis revealed that the ancient Egyptian drill performed 500 times greater per revolution than modern drills! He observed that ultrasonic drilling would be capable of the feats seen by Petrie in the Valley Temple, but the ancient Egyptians of course did not possess ultrasonic drills.

What if the stones of the Great Pyramid were not quarried, but “made” on site? Joseph Davidovits first aired this theory in 1974. Professor Davidovits is an internationally renowned French scientist, who was honored by French President Jacques Chirac with one of France’s two highest honors, the Chevalier de l’Ordre National du Mérite, in November 1998. Davidovits

has a French degree in chemical engineering and a German doctorate degree (PhD) in chemistry, and was also a professor and founder of the Institute for Applied Archaeological Sciences, IAPAS, Barry University, Miami, Florida, from 1983 to 1989. He was a visiting professor at Penn State University, Pennsylvania, from 1989 to 1991, and has been professor and director of the Geopolymer Institute, Saint-Quentin, France, since 1979. He is a world expert in modern and ancient cements, as well as geosynthesis and man-made rocks, and is the inventor of geopolymers and the chemistry of geopolymerization. He is, in short, a scientific genius and the expert in his field, sometimes referred to as the “father of geopolymers.”

These are just the highlights; his CV is longer than most books. But the reason I list his career’s distinctions is that all of his scientific credibility has made virtually no dent in Egyptological circles, where archaeologists have largely disregarded his findings about how the pyramids—or at least the Great Pyramid—were

really

constructed. In his expert opinion, backed up by experiments and analysis, the stones of the Great Pyramid were not hewn from quarries and then transported; instead, rough stone was quarried, but then placed in a (wooden?) container with other materials, causing a chemical process that made what in simple terms some might call cement, but which in fact is a type of stone that even experts in the field have a hard time telling apart from natural rock.

From an engineering perspective, this technique would make the construction of the Great Pyramid much easier: There were no immense limestone blocks to be moved; there was no real need for a ramp, and the transportation of the stone material could be done faster, as less care was required in moving the limestone; it was merely an ingredient, and if it broke, no one cared. Furthermore, the technique could also explain how the tremendous accuracy in the construction of the pyramid was achieved—the famous “no cigarette paper is able to be fitted

between two stones.” Rather than figuring out how two hewn stones were perfectly fitted to each other on site, instead, we would have wooden molds that were placed next to a completed “block,” upon which “cement” was poured into the mold, then left to dry, before the next stone was made. This guaranteed that each one fitted perfectly to the next.

This theory also fits in with the evidence on the ground. Some of the blocks that were allegedly hewn have large lumps trapped within the mass; others have wavy strata; others have differences in density between the stones of the pyramids and the natural stones as located in the quarries; and there is a general absence of any horizontal orientation of the shells in the pyramid blocks, when normal sedimentation would be expected to result in shells lying flat. All of these are telltale signs for an expert like Davidovits that the stones were cast, not hewn.

For us to accept that the blocks were cast, the only missing ingredient is whether or not the ancient Egyptians were familiar with such “rock making,” of geopolymerization. Davidovits is the world expert in this technology, and it is fair to say that not a single Egyptologist was aware of it until Davidovits first proposed his hypothesis. Specifically throughout the past three decades, Davidovits has been trying to educate this group of scientists, but they remain largely unwilling students, even though he sold more than 45,000 copies of his book when it appeared in 1988. The general public wanted to understand, but Egyptologists lacked the credentials to criticize his work, and they chose to ignore it. Today, there seems to be something of an Anglo-Saxon conspiracy against his theories, as Davidovits’s books are easily published by respected houses in France and other countries, yet

They Built the Great Pyramid

was self-published in its English edition.

Other books

Standing Up For Grace by Kristine Grayson

Waiting for Spring by Cabot, Amanda

Three Times the Scandal by Madelynne Ellis

Play Hard (The Devil's Share Book 5) by Maxa,L.P.

Captives of the Night by Loretta Chase

Secret Scorpio by Alan Burt Akers

Necropolis: London & it's Dead by Arnold, Catharine

What's His Is Mine by Daaimah S. Poole

IMPACT (Book 1): A Post-Apocalyptic Tale by Eliot, Matthew

Captivate, book I of the Love & Lust by Miles, Amy