The Ancient Alien Question (23 page)

Read The Ancient Alien Question Online

Authors: Philip Coppens

The Sacred Valley of Peru descends from Lake Titicaca, via Cuzco and Ollantaytambo, to Macchu Picchu and beyond. It was the path walked by the civilizing deity Viracocha, which is why the valley is sacred. Based on the extraordinary engineering features found in the various monuments, the idea of an otherworldly interference is not incredible.

The Sacred Valley begins at the Bolivian altiplano around Lake Titicaca, continues to Cuzco (literally the “navel” of the Inca world), to Macchu Picchu, the best-known Inca structure, rediscovered by Hiram Bingham in 1911. Situated at an altitude of 12,000 feet, Lake Titicaca is the highest navigable lake in the world. It was on an island in this lake, the Island of the Sun, that the Inca legends state that the creator god, Viracocha, appeared on Earth, and it was here that Viracocha’s voyage to spread civilization to the people of this region began.

Lake Titicaca is the highest navigable lake in the world. It is seen as the site where the Inca deity Viracocha emanated on this planet. The borders of the lake hold some of the most extraordinary archaeological sites, speicifically Tiahuanaco and Puma Punku.

In April 2004, I was fortunate enough to follow in the footsteps of Viracocha, using a lovely single-track train that runs through some of the most spectacular scenery in the world. From Lake Titicaca, which is so high that it is physically hard to breathe, the valley descends to 11,155 feet in Cuzco and 9,186 feet in Macchu Picchu. From here, Viracocha continued on his

path, walking southeast to northwest, until he reached the Pacific Ocean and disappeared, his mission accomplished.

The legend of Viracocha and how he “walked” the Sacred Valley brings us face to face with the enigmas of the Inca civilization. The structures that we see today at Ollantaytambo or Cuzco are reminders in stone of the “Holy Road” traveled by the Creator God.

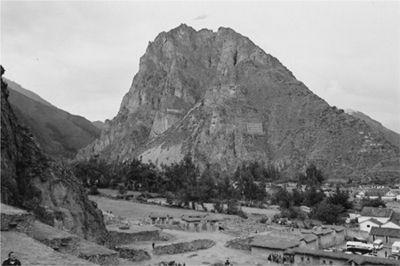

Ollantaytambo is built at an altitude that makes it almost impossible to believe that such gigantic stones went into the construction of the temple complex. But its location here was predicated on the presence of a sacred feature on the hill that overlooked the site: Its slope revealed a face, which was that of the god Viracocha himself.

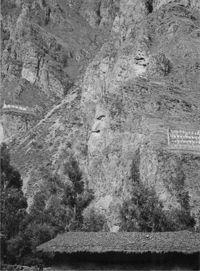

At Ollantaytambo, the profile of a human being, identified with Viracocha, can clearly be distinguished in the mountain that overlooks the complex. The Salazar brothers have furthermore identified that the temple at Ollantaytambo is aligned to certain notches in that hill, the alignment of which coincides with important sunrise events in the calendar. This complex contains massive stones, specifically the so-called Wall of the Six Monoliths, which

is precisely what the name suggests: a wall made up of six gigantic monoliths, apparently left unfinished, even though this area was the main structure of the Temple Hill, commonly known as the Fortress because of the gigantic blocks used in its construction. Parts of this temple were constructed with huge red porphyry (pink granite) boulders. The stone quarry for this extremely hard type of stone was 2.5 miles away, on the other side of the valley in which runs the Urubamba River. Stated that way, it might not sound like much, but when you are standing on the Fortress and looking in the direction where these stones came from, it feels like an impossible task. The valley is deep, the mountain altitude high—just under 9,000 feet. A. Hyatt & Ruth Verrill, in

America’s Ancient Civilizations

, sum up the enigma: “How were such titanic blocks of stone brought to the top of the mountain from the quarries many miles away? How were they cut and fitted? How were they raised and put in place? No one knows, no one can even guess. There are archaeologists, scientists, who would have us believe that the dense, hard andesite rock was cut, surfaced and faced by means of stone or bronze tools. Such an explanation is so utterly preposterous that it is not even worthy of serious consideration. No one ever has found anywhere any stone tool or implement that would cut or chip the andesite, and no bronze ever made will make any impression upon it.”

A detail of the hill that overlooks the temple complex of Ollantaytambo. A section of the hil clearly reveals a face, which has been linked with the god Viracocha, the civilizing deity of the Inca.

The stone face of Viracocha towering over Ollantaytambo is the key to why massive blocks were positioned here; his face shows that the Creator God is still present, watching over his people. But whereas most attention goes to the massive stone blocks of the Temple Hill, the Salazar brothers have identified that in the valley below, the first beam of the sunrise falls on the so-called Pacaritanpu, the House of Dawn, where the gods became “God.” This structure is hardly identifiable, unless it is looked upon with the “right eyes.” At first, there appears to be nothing but a cultivated field near the river. Though dating from the Inca time period, it is hardly recognizable as important. But a second glance will reveal that the entire field portrays a gigantic pyramid; this two-dimensional structure is viewed as a three-dimensional pyramid. And this is not a mere trick of the eye, as the position where the sunbeam hits the ground has been clearly and uniquely marked by a stone structure.

Such subliminal images in the Inca structures are not unique. Elsewhere, the Inca used the same technique, often in city planning. The Salazar brothers have identified various animal forms in the hills and designs of Macchu Picchu. The design of the capital Cuzco is equally ingeniously created to form the image of a puma, the royal animal. Many of these constructions were achieved by using a mixture of natural shapes, which were then augmented—“stressed”—by human intervention, often by creating fields in very specific shapes.

The notion that sacred geography underlines Inca city planning is not a new observation. The Jesuit Father Bernabe Cobo, in his book

The History of the New World

(1653), wrote about “ceques” in Cuzco. These were lines on which “wak’as”—shrines—were placed and which were venerated by local people. Ceques

had been described as sacred pathways, similar to the straight lines that can be found in Nazca. Cobo described how ceques radiated outward from the Temple of the Sun at the center of the old Inca capital. These were invisible lines, only apparent in the alignments of the wak’as. The ceques radiated out between two lines at right angles, which divided the city into four zones and extended farther out into the Inca Empire, which is how the empire got its name: Tawantinsuyu, meaning “Four Quarters of the Earth.”

When Macchu Picchu was discovered in 1911, its beauty and majesty made it a must-visit place. Though the stones used in its construction are not as massive as elsewhere in Peru, its location makes it part of a sacred pattern that involved the wanderings of the civilizing deity Viracocha.

Cuzco was the Inca capital; its original Quechua name was Qosqo, meaning “navel.” It is here that some of the most impressive stone masonry of South America is on display. The Dominican Priory and Church of Santo Domingo were built on top of the impressive Coricancha (Temple of the Sun), in an effort to prevent the local population from continuing to

worship Viracocha. When the Spaniards arrived in Cuzco, they saw 4,000 priests serving at the Coricancha. Ceremonies were conducted around the clock. Little remains of the Coricancha today, but what is left shows how impressive it was. The granite walls were once covered with more than 700 sheets of pure gold, each weighing around 4.5 pounds. The courtyard was filled with life-size sculptures of animals and a field of corn, all fashioned from pure gold. Even the floors of the temple were covered in solid gold. Facing the rising sun stood a massive golden image of the sun, encrusted with emeralds and other precious stones. At the center of the temple was the true navel—the Cuzco Cara Urumi, the “Uncovered Navel Stone.” This was an octagonal stone coffer covered with 120 pounds of pure gold.

Remarkable stonework built by pre-Inca people who lived in Peru can be seen in various locations, but one of the more interesting and accesible sites is the streets around the Coricancha in the “navel” of the Inca capital of Cuzco.