The Andromeda Strain (31 page)

Read The Andromeda Strain Online

Authors: Michael Crichton

Tags: #Thrillers, #Science Fiction, #Suspense, #High Tech, #Fiction

One is reminded of Montaigne’s acerbic comment: “Men under stress are fools, and fool themselves.” Certainly the Wildfire team was under severe stress, but they were also prepared to make mistakes. They had even predicted that this would occur.

What they did not anticipate was the magnitude, the staggering dimensions of their error. They did not expect that their ultimate error would be a compound of a dozen small clues that were missed, a handful of crucial facts that were dismissed.

The team had a blind spot, which Stone later expressed this way: “We were problem-oriented. Everything we did and thought was directed toward finding a solution, a cure to Andromeda. And, of course, we were fixed on the events that had occurred at Piedmont. We felt that if we did not find a solution, no solution would be forthcoming, and the whole world would ultimately wind up like Piedmont. We were very slow to think otherwise.”

The error began to take on major proportions with the cultures.

Stone and Leavitt had taken thousands of cultures from the original capsule. These had been incubated in a wide variety of atmospheric, temperature, and pressure conditions. The results of this could only be analyzed by computer.

Using the GROWTH/TRANSMATRIX program, the computer did not print out results from all possible growth combinations. Instead, it printed out only significant positive and negative results. It did this after first weighing each petri dish, and examining any growth with its photoelectric eye.

When Stone and Leavitt went to examine the results, they found several striking trends. Their first conclusion was that growth media did not matter at all—the organism grew equally well on sugar, blood, chocolate, plain agar, or sheer glass.

However, the gases in which the plates were incubated were crucial, as was the light.

Ultraviolet light stimulated growth under all circumstances. Total darkness, and to a lesser extent infrared light, inhibited growth.

Oxygen inhibited growth in all circumstances, but carbon dioxide stimulated growth. Nitrogen had no effect.

Thus, best growth was achieved in 100-per cent carbon dioxide, lighted by ultraviolet radiation. Poorest growth occurred in pure oxygen, incubated in total darkness.

“What do you make of it?” Stone said.

“It looks like a pure conversion system,” Leavitt said.

“I wonder,” Stone said.

He punched through the coordinates of a closed-growth system. Closed-growth systems studied bacterial metabolism by measuring intake of gases and nutrients, and output of waste products. They were completely sealed and self-contained. A plant in such a system, for example, would consume carbon dioxide and give off water and oxygen.

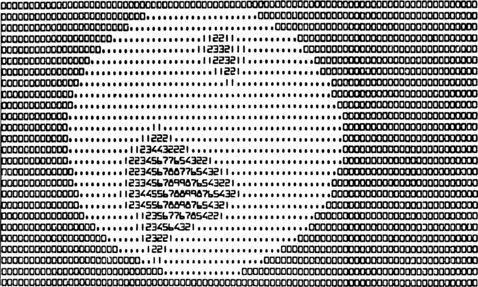

CULTURE DESIG – 779.223,187,

ANDROMEDA

MEDIA DESIG — 779

ATMOSPHERE DESIG — 223

LUMIN DESIG – L87 UV/HI

FINAL SCANNER PRINT

An example of a scanner printout from the photoelectric eye that examined all growth media. Within the circular petri dish the computer has noted the presence of two separate colonies. The colonies are “read” in two-millimeter-square segments, and graded by density on a scale from one to nine.

But when they looked at the Andromeda Strain, they found something remarkable. The organism had no excretions. If incubated with carbon dioxide and ultraviolet light, it grew steadily until all carbon dioxide had been consumed. Then growth stopped. There was no excretion of any kind of gas or waste product at all.

No waste.

“Clearly efficient,” Stone said.

“You’d expect that,” Leavitt said.

This was an organism highly suited to its environment. It consumed everything, wasted nothing. It was perfect for the barren existence of space.

He thought about this for a moment, and then it hit him. It hit Leavitt at the same time.

“Good Christ.”

Leavitt was already reaching for the phone. “Get Robertson,” he said. “Get him immediately.”

“Incredible,” Stone said softly. “No waste. It doesn’t require growth media. It can grow in the presence of carbon, oxygen, and sunlight. Period.”

“I hope we’re not too late,” Leavitt said, watching the computer console screen impatiently.

Stone nodded. “If this organism is really converting matter to energy, and energy to matter—directly—then it’s functioning like a little reactor.”

“And an atomic detonation …”

“Incredible,” Stone said. “Just incredible.”

The screen came to life; they saw Robertson, looking tired, smoking a cigarette.

“Jeremy, you’ve got to give me time. I haven’t been able to get through to—”

“Listen,” Stone said, “I want you to make sure Directive 7–12 is not carried out. It is imperative: no atomic device must be detonated around the organisms. That’s the last thing in the world, literally, that we want to do.”

He explained briefly what he had found.

Robertson whistled. “We’d just provide a fantastically rich growth medium.”

“That’s right,” Stone said.

The problem of a rich growth medium was a peculiarly distressing one to the Wildfire team. It was known, for example, that checks and balances exist in the normal environment. These manage to dampen the exuberant growth of bacteria.

The mathematics of uncontrolled growth are frightening. A single cell of the bacterium

E. coli

would, under ideal circumstances, divide every twenty minutes. That is not particularly disturbing until you think about it, but the fact is that bacteria multiply geometrically: one becomes two, two become four, four become eight, and so on. In this way, it can be shown that in a single day, one cell of

E. coli

could produce a super-colony equal in size and weight to the entire planet earth.

This never happens, for a perfectly simple reason: growth cannot continue indefinitely under “ideal circumstances.” Food runs out. Oxygen runs out. Local conditions within the colony change, and check the growth of organisms.

On the other hand, if you had an organism that was capable of directly converting matter to energy, and if you provided it with a huge rich source of energy, like an atomic blast …

“I’ll pass along your recommendation to the President,” Robertson said. “He’ll be pleased to know he made the right decision on the 7–12.”

“You can congratulate him on his scientific insight,” Stone said, “for me.”

Robertson was scratching his head. “I’ve got some more data on the Phantom crash. It was over the area west of Piedmont at twenty-three thousand feet. The post team has found evidence of the disintegration the pilot spoke of, but the material that was destroyed was a plastic of some kind. It was depolymerized.”

“What does the post team make of that?”

“They don’t know what the hell to make of it,” Robertson admitted. “And there’s something else. They found a few pieces of bone that have been identified as human. A bit of humerus and tibia. Notable because they are clean—almost polished.”

“Flesh burned away?”

“Doesn’t look that way,” Robertson said.

Stone frowned at Leavitt.

“What

does

it look like?”

“It looks like clean, polished bone,” Robertson said. “They say it’s weird as hell. And there’s something else. We checked into the National Guard around Piedmont. The 112th is stationed in a hundred-mile radius, and it turns out they’ve been running patrols into the area for a distance of fifty miles. They’ve had as many as one hundred men west of Piedmont. No deaths.”

“None? You’re quite sure?”

“Absolutely.”

“Were there men on the ground in the area the Phantom flew over?”

“Yes. Twelve men. They reported the plane to the base, in fact.”

Leavitt said, “Sounds like the plane crash is a fluke.”

Stone nodded. To Robertson: “I’m inclined to agree with Peter. In the absence of fatalities on the ground …”

“Maybe it’s only in the upper air.”

“Maybe. But we know at least this much: we know how Andromeda kills. It does so by coagulation. Not disintegration, or bone-cleaning, or any other damned thing. By coagulation.”

“All right,” Robertson said, “let’s forget the plane for the time being.”

It was on that note that the meeting ended.

Stone said, “I think we’d better check our cultured organisms for biologic potency.”

“Run some of them against a rat?”

Stone nodded. “Make sure it’s still virulent. Still the same.”

Leavitt agreed. They had to be careful the organism didn’t mutate, didn’t change to something radically different in its effects.

As they were about to start, the Level V monitor clicked on and said, “Dr. Leavitt. Dr. Leavitt.”

Leavitt answered. On the computer screen was a pleasant young man in a white lab coat.

“Yes?”

“Dr. Leavitt, we have gotten our electroencephalograms back from the computer center. I’m sure it’s all a mistake, but …”

His voice trailed off.

“Yes?” Leavitt said. “Is something wrong?”

“Well, sir, yours were read as grade four, atypical, probably benign. But we would like to run another set.”

Stone said, “It must be a mistake.”

“Yes,” Leavitt said. “It must be.”

“Undoubtedly, sir,” the man said. “But we would like another set of waves to be certain.”

“I’m rather busy now,” Leavitt said.

Stone broke in, talking directly to the technician. “Dr. Leavitt will get a repeat EEG when he has the chance.”

“Very good, sir,” the technician said.

When the screen was blank, Stone said, “There are times when this damned routine gets on anybody’s nerves.”

Leavitt said, “Yes.”

They were about to begin biologic testing of the various culture media when the computer flashed that preliminary reports from X-ray crystallography were prepared. Stone and Leavitt left the room to check the results, delaying the biologic tests of media. This was a most unfortunate decision, for had they examined the media, they would have seen that their thinking had already gone astray, and that they were on the wrong track.

25

Willis

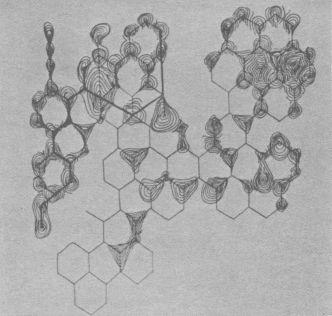

X-RAY CRYSTALLOGRAPHY ANALYSIS showed that the Andromeda organism was not composed of component parts, as a normal cell was composed of nucleus, mitochondria, and ribosomes. Andromeda had no subunits, no smaller particules. Instead, a single substance seemed to form the walls and interior. This substance produced a characteristic precession photograph, or scatter pattern of Xrays.

Looking at the results, Stone said, “A series of six-sided rings.”

“And nothing else,” Leavitt said. “How the hell does it operate?”

The two men were at a loss to explain how so simple an organism could utilize energy for growth.

“A rather common ring structure,” Leavitt said. “A phenolic group, nothing more. It should be reasonably inert.”

“Yet it can convert energy to matter.”

Leavitt scratched his head. He thought back to the city analogy, and the brain-cell analogy. The molecule was simple in its building blocks. It possessed no remarkable powers, taken as single units. Yet collectively, it had great powers.

“Perhaps there is a critical level,” he suggested. “A structural complexity that makes possible what is not possible in a similar but simple structure.”

“The old chimp-brain argument,” Stone said.

Leavitt nodded. As nearly as anyone could determine, the chimp brain was as complex as the human brain. There were minor differences in structure, but the major difference was size—the human brain was larger, with more cells, more interconnections.

And that, in some subtle way, made the human brain different. (Thomas Waldren, the neurophysiologist, once jokingly noted that the major difference between the chimp and human brain was that “we can use the chimp as an experimental animal, and not the reverse.”)