The Annals of Unsolved Crime (20 page)

Read The Annals of Unsolved Crime Online

Authors: Edward Jay Epstein

The consensus theory in law-enforcement circles is that Hoffa was murdered at the behest of Mafia leaders out of concern that he would regain control of the Teamsters. A fifty-six-page report prepared by the FBI in January 1976 states that it is probable that Hoffa was murdered by organized crime figures to prevent him from regaining control over the union’s pension fund. A second theory is that Tony Provenzano had him killed as part of an internal power struggle for control of the Teamsters. Proponents of this theory point out that Hoffa had become a problem for Provenzano, and that there was a history of other enemies of Provenzano disappearing. Three years earlier, a man allegedly involved in counterfeiting money with Provenzano had disappeared. So did Tony Castellito, the treasurer of Provenzano’s local union chapter. Finally, there is the theory that Hoffa was killed by his own adopted son, Charles O’Brien. Through DNA analysis in the 1990s, investigators found a hair that matched Hoffa’s DNA in a Mercury that had been driven by O’Brien. Witnesses told the FBI that O’Brien had strongly opposed Hoffa’s plan to run in the Teamsters election in 1975. But O’Brien had an alibi: at the time of Hoffa’s disappearance witnesses saw him cutting a forty-pound frozen salmon into steaks at the home of a Teamsters official.

My assessment is that the absence of evidence is itself a clue to who abducted Hoffa. The disappearance was so professionally accomplished that a twenty-five-year investigation failed to turn up a body, signs of a struggle, witnesses, or any forensic evidence (DNA evidence could not have been foreseen in 1975), and the obvious suspects also had convenient alibis. This organization indicates that Hoffa’s elimination was a well-planned operation carried out by criminals who were

experienced in murder and who also had the influence among Hoffa’s associates to assure that he would go to a prearranged meeting. This persuades me that the FBI was correct in attributing his disappearance to organized crime.

It is difficult, if not impossible, to solve a murder if the corpse vanishes and does not resurface. This is especially true if there are no witnesses. There is no body and no crime scene.

PART FOUR

CRIMES OF STATE

CHAPTER 22

DEATH IN UKRAINE: THE CASE OF

THE HEADLESS JOURNALIST

I.

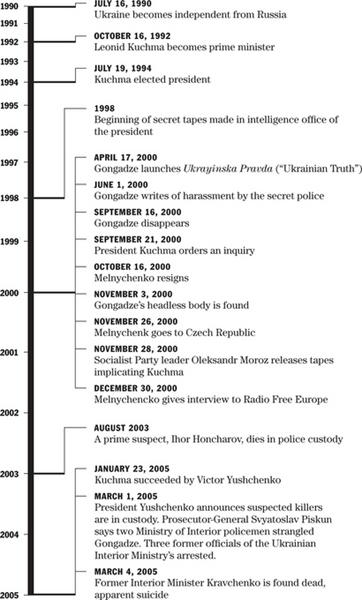

A journalist is decapitated in Ukraine. The president of Ukraine is implicated in the murder by secret tape recordings. The Minister of the Interior supposedly commits suicide by shooting himself in the head, using two shots. The Minister’s two top deputies are eliminated as witnesses, the first by a fatal heart attack, the second as the result of a coma that leaves him brain-dead. The government itself is destabilized by the release of the secret recordings of the president, which are posted on a website financed by a Russian billionaire exiled in London. Intertwined in the case of the headless journalist are four separate types of political crime: murder, cover-up, espionage, and coup d’état.

The murder took place in 2000 outside Ukraine’s capital city, Kiev. The victim was Georgiy Gongadze, the thirty-one-year-old Georgian-born editor who co-founded

Ukrayinska Pravda

(“Ukrainian Truth”), a website created earlier that year, which conducted relentless attacks on Leonid Kuchma, who in 1996, after serving as prime minister, had been elected president. Ukraine, Europe’s second-largest country, was still politically fragile, having only become independent of Russia nine years earlier.

Gongadze was not the first Ukrainian journalist to disappear or die under suspicious circumstances during the Kuchma regime, but his death was immediately considered suspicious because he had published an open letter complaining of harassment by the domestic security service, known by its Russian initials as the SBU, shortly before his disappearance. When he was reported missing on September 17, 2000, a large crowd, led by journalists carrying placards with Gongadze’s photograph on them, occupied Kiev’s main square. These demonstrations grew to more than 100,000 protesters, effectively paralyzing the government of Ukraine.

Then, on November 3, 2000, a headless body was found in a shallow grave in a forest forty-three miles from Kiev. What remained of the corpse had been badly disfigured by dioxin, which pathologists concluded may have been poured on the victim while he was still alive. The corpse then inexplicably vanished from the custody of the local police and only later re-emerged in a morgue in Kiev, along with some of Gongadze’s personal effects. A subsequent DNA analysis performed by a U.S. military lab determined with 99.6 percent certainty that it was the remains of Gongadze. Witness testimony also established that he had been kidnapped from Kiev, after dining with a female friend on September 16, 2000.

Initially, police attributed the murder to common criminals, eventually arresting a suspect, who died in custody, but on November 28, Oleksandr Moroz, the leader of the main opposition party, made public the contents of stolen tape recordings that purported to be the secret deliberations of Kuchma and his cabinet. In one of these tapes, a voice sounding like President Kuchma can be heard discussing Gongadze. It said “Throw him out! Give him to the Chechens!” This sensational disclosure undermined the regime of President Kuchma and eventually made him a suspect in Gongadze’s murder.

The “Cassette Scandal,” as it was called, convulsed the

nation for the next five years. It proceeded from a two-year espionage operation allegedly run by Major Mykola Melnychenko, a KGB-trained counterintelligence officer, who served as Kuchma’s electronic security chief. Supposedly, more than 200 hours of secret discussions in the inner sanctum of Kuchma’s government had been recorded from early 1998 to September 16, 2000, by Major Melnychenko on a store-bought Toshiba dictation machine. But before he could be questioned, Melnychenko left Ukraine with his family.

At first, the government declared the tapes to be crude forgeries, but members of the government recorded on the tapes identified their voices, and independent forensic examinations showed that the recordings had no obvious signs of being forged. The examinations did not rule out the possibility, however, that the tapes had been edited or doctored by using sophisticated techniques.

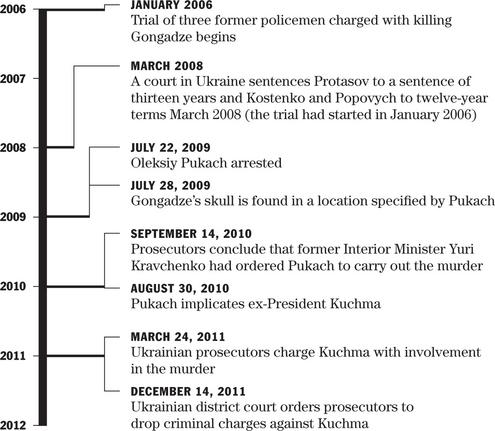

In 2005, after Kuchma was replaced as president and the so-called Orange Revolution swept away much of his regime, a new investigation of the murder of Gongadze resulted in the eventual arrest of three SBU agents who had been part of a surveillance team watching Gongadze. They were Valeriy Kostenko, Mykola Protasov, and Oleksandr Popovych. The legal process dragged on for another five years. After they were charged with murdering and decapitating him, they confessed and implicated their immediate superior, General Aleksiy Pukach, who they said had actually strangled Gongadze. General Pukach then disappeared, and remained a fugitive for more than four years, before being arrested in July 2009. As all the legal proceedings against him were conducted behind closed doors to preserve state secrets, I obtained his account through lawyers involved in the case. Pukach not only admitted his role in the crime, but he led investigators to the missing head, which he had buried near a tree. This admission solved the mystery of who had killed Gongadze: it was a political crime

undertaken by the security apparatus of the government. But the real issue, as in all political crimes, is who was ultimately responsible.

The Prosecutor General stated that the orders were given by Interior Minister Yuri Kravchenko, for whom General Pukach worked. Kravchenko had also been a participant in the recorded conversations about Gongadze in the summer of 2000. But Kravchenko could no longer be questioned, since on March 4, 2005, he died of gunshot wounds in his home in Kiev. As he had left a note, authorities declared his death a suicide. Even so, many observers remained unconvinced that he had killed himself. The medical examination showed that Kravchenko had two gunshot wounds in his head. One bullet had struck him in his chin and the other in his temple. As Mykola Polishchuk, Ukraine’s former health minister and an authority on firearm wounds, noted “The direction of the wound is uncharacteristic of a wound inflicted by the person himself, because it travels from bottom to top and from inside to outside. It is extremely difficult to believe that a person would be capable of injuring himself in this way.”

The only remaining lead in the investigation came from one of the convicted SBU agents, General Pukach’s driver, Olexsandr Popovych. He testified at his trial that a few weeks after Gongadze’s decapitation, he had driven the general to a meeting at a restaurant with two of Kravchenko’s top intelligence deputies, Major General Yuri Dagaev and Eduard Feres, and overheard them discussing the need to re-bury the headless corpse. But neither of these men could be questioned: in 2003, General Dagaev had died of an apparent heart attack at age fifty-three; Feres was in a vegetative coma, and he died in 2009.

Even so, on March 24, 2011, Ukrainian prosecutors moved against ex-President Kuchma. On the basis of what was supposedly said on the eleven-year-old recordings, they charged him with complicity in Gongadze’s murder.

II.

I met with Kuchma in Kiev on December 9, 2011, at offices inside the foundation he created. Although he had retired as president in January 2005, he still preferred to be called “Mr. President.” His red hair and youthful smile made him seem much younger than his seventy-three years. Although he spoke in Russian, with his lawyer acting as an English translator, he appeared to understand my questions, giving quick and focused answers.

He denied having any involvement in Gongadze’s murder. He acknowledged that the voice on the tapes was his, but he said that the tapes had been doctored to incriminate him.

He cited two independent forensic examinations showing that whatever had been originally recorded had been digitally transferred to a computer file. It was an MP3 file, not the original cassette tape recordings, that was released. Because of the digital conversion, it was not possible to determine how many devices were used in making the recordings, or the extent to which it had been tampered with.

Kuchma was convinced that the penetration of Ukraine’s inner sanctum was the work of a sophisticated intelligence operation. He said that his counterintelligence experts had reconstructed some of the recordings and come to the conclusion that the two-year espionage operation required the services of more than a single man. To capture all these recordings, according to this reconstruction, multiple microphones would have had to be implanted in walls and other places in which they would not be discovered by security sweeps.

In Kiev, I also interviewed the Ukrainian intelligence general who worked on this analysis. He agreed with Kuchma’s assessment, saying “These hundreds of hours of recording could not have all been done by Melnychenko.” He pointed out that there were two different teams that checked the room before every cabinet meeting, one from the foreign intelligence service and the other, which Melnychenko headed, from Domestic Security. Indeed, one purpose of this redundancy was to allow the two intelligence organizations to keep an eye on each other. Under this arrangement, the general explained, Melnychenko could not have simply slipped a dictation machine under a sofa without it being detected. Nor could he have simply left the machine unattended for more than a day, since the batteries would have to be changed daily. “This operation required the sort of equipment that has been developed by espionage services like the KGB,” he said. “Melnychenko’s claim that he acted alone is merely a convenient cover for those responsible.” If so, Melnychenko had been working for an intelligence service with the wherewithal to penetrate a president’s lair, after which he had exposed the operation by releasing the recordings. When I asked the general why an intelligence service would allow its secret sources and methods to be compromised in this way, he replied that perhaps it was not its decision.

Kuchma made it clear to me that he believed Melnychenko was part of a plot to drive him from power, and that whoever was behind the plot wanted to be certain that Melnychenko was not questioned: A few days before the tapes were released, Melnychenko received a bogus passport from an unknown party and fled Ukraine. The Ukraine authorities could do no more than indict him for the theft of state secrets and conspiracy, charges which still stand.