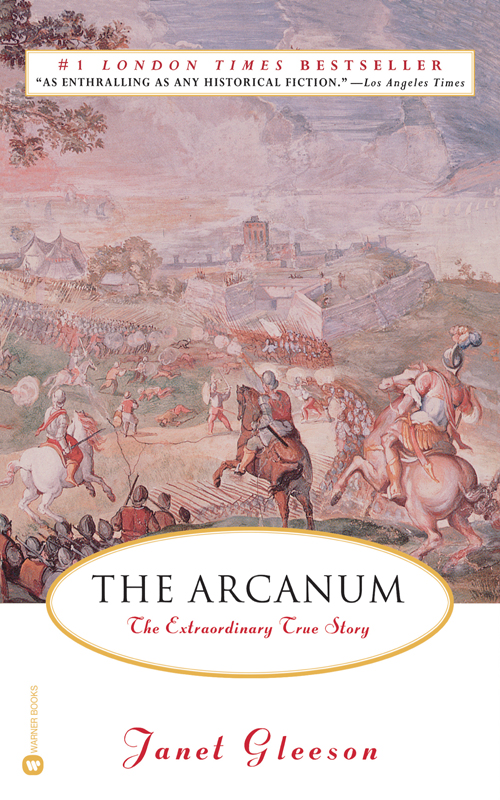

The Arcanum

Authors: Janet Gleeson

Copyright © 1998 by Janet Gleeson

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

First eBook Edition: September 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-56479-3

For Paul, Lucy,

Annabel and James

Contents

Chapter Two: Transmutation or Illusion

Chapter Three: The Royal Captor

Chapter Four: The China Mystery

Chapter Five: Refuge in Despair

Chapter Six: The Threshold of Discovery

Chapter Seven: The Flames Of Chance

Chapter Nine: The Price of Freedom

Chapter Two: The Porcelain Palace

Chapter Five: Scandal and Rebirth

Chapter Six: A Fantasy universe

Part Three: The Porcelain Wars

Chapter Two: The Porcelain Soldiers

Chapter Three: Visions of Life

Chapter Four: The Final defeat

Let me tell you further that in this province, in a city called Tinju, they make bowls of porcelain, large and small, of incomparable

beauty. They are made nowhere else except in this city; from here they are exported all over the world. These dishes are made

of a crumbly earth or clay which is dug as though from a mine and stacked in huge mounds and then left for thirty or forty

years exposed to wind, rain, and sun. By this time the earth is so refined that dishes made of it are of an azure tint with

a very brilliant sheen. You must understand that when a man makes a mound of this earth he does so for his children.

M

ARCO

P

OLO,

Description of the World

I

t all began with gold. Three centuries ago when this story begins there were two great secrets to which men of learning longed

to find the key. The first was almost as old as civilization itself: the quest for the arcanum or secret formula for the philosopher's

stone, a mysterious substance believed to have the power to turn base metal into gold and make men immortal. The second, less

esoteric but no less desired, was the arcanum for making porcelain—one of the most coveted and costly forms of art—gold in

the form of clay.

When the first steady trickle of Oriental porcelain began to reach Europe in the cargoes of Portuguese traders, kings and

connoisseurs were instantly mesmerized by its translucent brilliance. As glossy as the richly colored silks with which the

ships were laden, as flawlessly white as the spray which broke over their bows on their long treacherous journeys, this magical

substance was so eggshell fine that you could hold it to the sun and see daylight through it, so perfect that if you tapped

it a musical note would resound. Nothing made in Europe could compare.

Porcelain rapidly metamorphosed into an irresistible symbol of prestige, power and good taste. It was sold by jewelers and

goldsmiths, who adorned it with mounts exquisitely fashioned from gold or silver and studded with precious jewels, to be displayed

in every well-appointed palace and mansion. Everywhere, china mania ruled. While the demand for the precious cargo inexorably

mushroomed, so too did the prices for prime pieces. The money spent on acquiring porcelain multiplied alarmingly, fortunes

were squandered, families ruined, and China became Europe's bleeding bowl. Gradually it dawned on sundry ambitious princelings

and entrepreneurs that if they could only find a way to make true porcelain themselves this massive flow of cash to the Far

East could be diverted to their coffers and they would be preeminent among their peers. So the hunt began.

Samples of clays were gathered, travelers' tales of how Chinese porcelain was supposedly made were dissected and analyzed.

Ground glass was added in an effort to produce translucence; sand, bones, shells and even talcum powder were mixed in to give

pure whiteness, myriad different recipes for pastes and glazes tested. All was to no avail until, in 1708, after lengthy experiments

in a squalid dungeon, a disgraced young alchemist who thought he could make gold discovered the formula for porcelain, and

Europe's first porcelain factory, at Meissen, was born.

As in some enthralling fairy tale, the manufacture of porcelain was spawned by the age-old superstition that it was possible

to find a magical way to create gold, but it was also, ironically, a technological breakthrough that represented one of the

first major successes of analytical chemistry and the start of one of the earliest great manufacturing industries of Europe.

Even the Chinese were eventually obliged to acknowledge Meissen's ascendancy and began copying its designs. It remains to

this day the most outstanding ceramic manufacturer of all time.

This is the incredible but true story of the lives of the three men who solved one of the great mysteries of their day and

made porcelain to outshine that of the Orient: Johann Frederick Böttger, the alchemist who searched for gold and found porcelain,

but ultimately paid for the discovery with his life; Johann Gregor Herold, the relentlessly ambitious artist who developed

colors and patterns of unparalleled brilliance, exploiting numerous talented underlings as he did so; and Johann Joachim Kaendler,

the virtuoso sculptor who used the porcelain Meissen made to invent a new form of art. It is also the story of the unimaginable

treachery and greed that this discovery engendered; of a ruthlessly ambitious, spendthrift king, whose appetite for sensual

pleasure included an insatiable desire for porcelain; and of the cutthroat industrial espionage, eighteenth-century style,

that threatened the security of the arcanum.

Nearly three centuries later, porcelain no longer rules the hearts and minds of leading scientists, potentates and philosophers.

For most of us china does not represent a peerless treasure but something easily bought from a department store, given as

a wedding present or casually admired in a shop window: a familiar accoutrement of everyday life. These days, as we lay our

tables for dinner, raise a cup of coffee to our lips or rearrange the figures on a mantelpiece, it is scarcely remembered

that virtually every piece of china in some way owes a debt to the endeavors of these extraordinary men—or that porcelain

was once more precious than gold.

What better in all the world than that divine stone of the Chymists, yet men in the achieving of it, doe commonly hazard both

their braines and subsistence, and in case they come neer an end, it is a very good escape their glasses bee not melted or

broken, or evill spirits, as Flamell admonishes, does not through envy blinde their eys, and spoile all the worke.

J

OHN

H

ALL,

Paradoxes of Nature,

1650

E

scape was the only alternative. He had failed to fulfill his promise to the king and his life now hung in the balance. On

June 21, 1703, a dark-haired twenty-one-year-old prisoner gave the slip to his unsuspecting guards, stole from the confines

of his castle prison and found his way to the meeting place, where his accomplice waited with a horse ready harnessed for

a journey to freedom.

With a hastily murmured farewell and scarcely a backward glance, the fugitive mounted his horse and fled speedily through

Dresden's narrow medieval streets. Passing through the fortified city gates and across the bridge traversing the wide span

of the river Elbe, he hastened through the towns jumbled, dilapidated suburbs and then out onto the fertile plains surrounding

Saxony's capital city. Only once before had he glimpsed the lush panorama of fields filled with grain, flax, tobacco and hops,

and the vineyards laden with ripening grapes. That had been nearly two years before on his heavily guarded journey to captivity.

Ever since, he had been haunted by the fear that he would never be free to see it again.

As he rode southward the terrain became increasingly contoured and the roads more perilous. Rutted by spring rains and the

wheels of heavy wagons, the route wended its way toward a precipitous mountain pass skirting narrow ravines. But still the

fugitive sped on, spurred by the certainty that as soon as his disappearance was noticed a search party of soldiers would

be dispatched to recapture him. One did not escape the king easily, and success depended on the lead he could gain before

they followed. If he was recaptured the penalty would almost certainly be torture and death.

The name of this daredevil fugitive was Johann Frederick Böttger. At the time of his desperate escape he had been held as

a prisoner of Augustus II, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony, for nearly two years. The cause of his incarceration was

neither murder, nor theft, nor treason, merely his proclaimed belief that he was close to discovering the secret that virtually

every European monarch craved: the formula or arcanum for the philosopher's stone, the magical compound that would turn base

metal into gold. Augustus yearned to be the first to find someone who could unlock that mystery, and he was not about to let

a man who had promised to supply him with limitless wealth escape his clutches. Böttger had vowed to make gold and had failed

to provide it. He could not expect to be shown mercy.

Viewed from our comfortably superior twentieth-century perspective, the notion that, by means of little more than the simplest

laboratory equipment, some assorted ingredients and a few mystical words, any base metal might be transmuted into gold seems

unquestionably absurd. We now know that the only way one element can be changed into another is by harnessing the might of

nuclear technology and showering it with neutrons in a nuclear reactor. Even then the amount of gold that could be produced

in such a way would be infinitesimal compared with the energy and cost expended. But however far-fetched such a concept now

seems, transmutation—the ability to change one metal into another more valuable one—still obsessed men of learning and power

in the Europe of Augustus's day.