The Art of Holding On and Letting Go (23 page)

Read The Art of Holding On and Letting Go Online

Authors: Kristin Lenz

“To be honest, we only had money for one plane ticket, and I didn't want to ask Grandma and Grandpa to borrow any.” She reached out and tucked a strand of hair behind my ear. “I tried to come sooner, but a lot of flights were canceled because of the snow. It didn't feel like Christmas without you there with us.”

Tell me about it.

“How long are you staying?” I asked.

“A few days. Grandma and Grandpa said you were really sick. We were worried about you.”

I sighed and flopped back on my pillows. Even though I felt better, I was still shaky and weak. A layer of frost had crept onto my bedroom windowsill. The wind howled outside.

Mom's beaded bracelet from Ecuador, the twin of mine, was on her wrist.

Buena suerte para una madre y su hija.

She straightened and smoothed my covers, just like how she used to tuck me in as a little kid. My body melted to her touch.

“Grandma's making chicken noodle soup. I'll bring you some a little later,” she said. “Then we can call Dad. He can't wait to talk to you.”

I smiled and closed my heavy eyes.

The sun shone in patches of blue sky the next morning, the snowy yard sparkling and smooth except for a trail of squirrel prints.

“You feeling up for a walk?” Mom asked.

I nodded. Fresh air sounded great.

We bundled up and strolled down the block. Snow dusted off the tree branches, shining like glitter in the sunlight.

“I haven't heard from Coach Mel in a couple months,” I told Mom.

“Do you know why Coach spends more time teaching rather than climbing?” she asked.

I shrugged. “She's older.”

“Not much older than me,” Mom said. “A very long time ago, your coach lost her fiancé on a climb. They had just become engaged.”

Oh my god. What was with all these people dying? I knew Coach Mel had been one of the top sport climbers before she began coaching, but I had never heard about an accident.

“When we were missing on Chimborazo, it was really hard on her. And for you too, I know that, and I'm still very sorry. For Mellie, it stirred up her grief from years ago, especially when she heard about Max.”

“Why didn't she tell me?”

“She was just doing the best she knew.”

Coach Mel had tried to stay in touch, but I'd basically ignored her. I guess she understood more than I realized.

Clouds had moved in, covering the sun, and the cold air made my nose drip. I sniffed and tugged my hat further down over my ears.

“Let's turn around,” Mom said, linking her arm through mine. “You're not completely over this bug yet.”

Back inside, Mom watched as I tugged off my boots and shrugged out of my coat.

“What?” I said.

She shook her head, her lips curving into a soft smile. “It's only been a few months, but you've grown. You look so mature.” She ran her fingers through my hair. “Your hair is so long. You've grown out your bangs. It's darker too.”

“Not enough sun here.”

“You're beautiful.” She pulled me into a hug. “I love you so much.”

“I love you too, Mom,” I said, softening into her embrace. She smelled like the crisp fresh air.

She pulled back and cupped my face. “Do you have a boyfriend?”

I rolled my eyes.

“Uh-huh.” She turned to my Grandpa, sitting in his reading chair. “Spill the beans. Cara has a boyfriend, doesn't she?”

“Mom.”

Grandpa lowered the newspaper. “Boys are calling here every night, knocking on the door at all hours. We can't keep 'em away.”

“Grandpa!” I laughed. “Don't listen to him,” I told Mom.

“It won't be long,” she said. “Your dad's really not going to know what to do then.”

On New Year's Eve, I talked to Dad again. He yelled into the phone, his words slurred. “Cara! I wish you could see this. Do you hear it?”

Loud fizzes and pops, crackling and explosions. The noise nearly drowned out his voice. But he was still there, on the line, and I thought I heard him whimper, a sob breaking free.

I handed the phone to Mom. She looked at me questioningly. I swallowed, but couldn't speak. Dad crying. So brief, but horrible; a sob of pain escaping from deep within. I had never heard my dad cry before.

She listened for a minute, then said, “I love you,” and ended the call.

“He's had a little too much to drink,” she said.

“Is he okay? What was all that noise?”

“New Year's Day is a major celebration in Ecuador. Sort of how we talk about cleaning out the old to bring in the new. Their celebration is like a huge party in the streets. People dress up in costumes and make effigies out of old clothes, stuffing them with sawdust or newspapers and firecrackers. The effigies are called años viejos.”

Mom's Spanish had improved during the time she was away, and she pronounced the words without hesitation. Firecrackers, that was the noise I had heard. It sounded more exciting than the night Grandma and Grandpa had planned:

The Sound of Music

and popcorn.

“They build small huts out of eucalyptus, and the años viejos are put inside. At midnight, they're set on fire. It's quite dramatic. All of the hardships and troubles of the past year are burned away.”

In bed that night, fireworks and flames exploded behind my eyes. Instead of a eucalyptus hut, I saw our cabin bursting into flame, swept by the forest fire. And inside stood Uncle Max, looking out the window, not in fear, but in awe of the spectacle surrounding him.

The night before Mom left, she told me their plans. I had heard her correctly on the phone, they were training for K2. Uncle Max's dream, to summit the deadliest mountain on Earth.

I stared at her. Hard.

“I know what you're thinking,” she began.

“Really?” I snapped. “If you did, we'd be back home in California now. One out of every four people die trying to summit that mountain. That's what I'm thinking.”

Mom was quiet for a minute. I knew my stuff. K2 was called the Savage Mountain. The second highest after Everest, but even more dangerous. More climbers had died on K2 than on any other mountain due to its treacherous terrain and unpredictable, relentless storms. Not to mention that it was in Pakistan. Their journey would begin in Islamabad, right in the heart of a terrorist insurgency.

“Did Mr. S. ever tell you why he stayed in Ecuador?” she asked.

“No. What, he fell in love with the country?”

She shook her head. “He lost a partner on Mount Chimborazo.”

Mr. S. had definitely not shared this information with me. How could he? My own parents had been heading to Chimborazo and then were nearly killed.

“He's never been able to move on, to put it behind him. He's been stuck in the same place ever since,” Mom said. “If your dad can live out Max's biggest dream for him, I think he'll be able to truly move forward from there.”

So many arguments exploded in my mind. She'd just given me two more stories of climbers dying. The practical question jumped out.

“How are you going to pay for that kind of expedition?”

“That's the crazy thing. Like this was meant to be. Max's death brought more attention to us, our story. We didn't even have to seek out sponsors; they came to us. We'll never have this kind of opportunity again.”

What more was there to say? They couldn't even afford an extra plane ticket, but someone else was offering to fund their next summit attempt. Mom and Dad knew the risks. They'd been seeking and living these risks my whole life. It wasn't just fear that rippled inside my stomach, it was thrill. K2 was hard-core mountaineering land. Ascending this mountain of mystery was considered a far greater accomplishment than Everest. How many women had summited K2, ever? Ten? Fifteen? My mom could join their ranks.

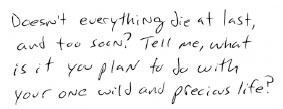

The day after Mom left, another Ecuador postcard arrived from Dad. On the back, he'd scrawled:

Mary Oliver. I sighed. What was he trying to tell me now? I wished the postcard had arrived when Mom was still here, so I could ask her. Was Dad trying to explain what he was doing, or was he asking me what I planned to do?

Mom was returning to Dad to train for their most perilous climbing expedition yet, and I was expected to stay here and finish school. Stuck in the “hills” of Detroit. I was going to have to find my own way back home. To my own wild and precious life.

I was healthy again, the snow melted, and school grew interesting after winter break. It was time for all juniors to take a three-week Health Seminar on Human Sexuality. Sex Ed. Letters were sent home giving parents the opportunity to excuse their child from the course if the content was objectionable. Grandpa chuckled when he saw the letter, but Grandma screwed up her mouth and said, “Well, I hope this is an abstinence-based program.”

“Don't think so, Margaret. Says here the class will discuss all methods of birth control in the context of healthy relationships.”

“Fat lot of good that did Lori,” Grandma muttered.

“But she gave us Cara.”

“Cara could have come after Lori finished college if it wasn't for Mark and that hippie-dippie commune in the woods.”

My grandparents were actually talking about sex. In front of me. I fled for my room. Mom got pregnant with me when she was only twenty. She had taken a year off from college and was living and working with my dad in the mountains. Instead of returning to school, she had me. From what I'd been able to patch together, this was the start of the conflict between my parents and grandparents. Then when Mom and Dad proceeded to travel around the world, climbing, with me in tow, things really got ugly.

But maybe there was even more to it. I was an accident. My mom had had me without even trying. It hadn't been so easy for Grandma. Back at school, everyone was talking about sex ed and the upcoming Sadie Hawkins dance where the girls were supposed to ask the guys. Hormones swirled through the hallways like gusts of wind before a storm. I couldn't stop thinking about Tom. I was on the lookout for him in between every class. I made sure I walked by his locker first thing in the morning and at the end of the day. In Algebra II, I oh-so-casually strolled over to the pencil sharpener whenever he was there.

“Hola, muchacha. Regular or the super special?”

I smiled and handed over my pencil, wishing I could think of a smart comeback.

“Super special it is.” And he hunched down and grinned that amazingly cute grin.

Grandpa had bought me a mechanical pencil with refillable lead. No way was I using it.

At lunchtime, I met Kaitlyn as usual at the fringe of the goth table.

“Nick won't be here,” she said. “He got sent to the office.”

“How come?”

“His T-shirt. Did you see it?”

“Uh-uh, he still had his coat on when I saw him this morning.”

“It said âson of a bââ' on the front.”

“Who sent him to the office?”

“Mrs. Cooper, AP English. Nick calls her Mrs. Plaster, you know, the one who wears so much foundation it looks like you could smack her on the back of her head and her face would crack.”

“So what'll happen?”

“Nothing. They'll make him turn it inside out. But it's good he's gone 'cause we gotta talk. I think we should go to Sadie Hawkins.”

“I thought you didn't like that kind of stuff,” I said.

“I don't. I mean I don't know. I used to, before, you know. I've just been thinking, and I think it would be good for us. To get out, you know, and try to move, like forward or something.”

I burst out laughing, I couldn't help it. “Smooth, Kaitlyn.”

“You know what I mean.”

“Who would you ask?”

“I was thinking about asking Tom Torres,” she said.

My eyes popped.

“Psych! Just kidding! He's all yours.”

“No way am I asking him.”

“You have to! This is the perfect chance.”

“I thought we were talking about you?”

“There's not really anyone I like. So I was thinking about asking Nick, you know, to go as friends.”

“You do like him, don't you?”

“Please, I told you, he's totally gay.”

“Uh-uh, he's so in love with you.”

Kaitlyn stuck her tongue out at me. “Is not. At this very moment, Virgin Goth Girl is waiting outside the office for him. She's probably going to ask him to Sadie Hawkins, and then we'll have to come up with a Plan B.”

“Virgin Goth Girl?”

“You know, Ashley, the one who usually sits over there, always wears white, ruffly peasant shirts and dresses, and those lace-up boots.”

“I thought goths always wore black.”

“You have so much to learn. Being goth is about expressing yourself as a unique personâwe don't follow a mold.”

Except for Virgin Goth Girl, they all looked pretty much the same to me. But I didn't say that to Kaitlyn. It wasn't like I had any style of my own. I didn't buy my jeans with artfully ripped holes; they were thin and torn at my knee from wearing them so much.