The Art of Waiting

Read The Art of Waiting Online

Authors: Christopher Jory

The Art of Waiting

First published in Great Britain in 2015 by

Polygon, an imprint of Birlinn Ltd.

West Newington House

10 Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

Copyright © Christopher Jory, 2015

The moral right of Christopher Jory to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved.

Quotation by Georgi Litichevsky is from

The Meaning of Life

(Time Inc. Magazine Company, 1991)

ISBN 978 1 84697 308 6

eBook ISBN 978 0 85790 839 1

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available on request from the British Library.

Typeset by

3btype.com

Contents

Tambov Prison Camp 188, Russia, April 1943

PART THREEÂ Â Â Â Russia and Ukraine

Near Rostov-on-Don, August 1942

Pavlovsk, near Rostov-on-Don, December 1942

Pavlovsk, near Rostov-on-Don, January 1943

Tambov Prison Camp 188, March 1943

Life means love. We are here for love. Only love is real, and everything is real thanks to love. We are nomads wandering through illusionary space. How to make it real? Only by destroying limits that separate us from others. No violence, no attempts at escape can help, only love. Too often love is more painful than joyful. The instances of love are much shorter than the periods during which we wait for love to emerge. The meaning of living is mastering the art of waiting.

Georgi Litichevsky, Ukrainian artist

For my wife, Lioudmila

Hope

Tambov Prison Camp 188, Russia, April 1943

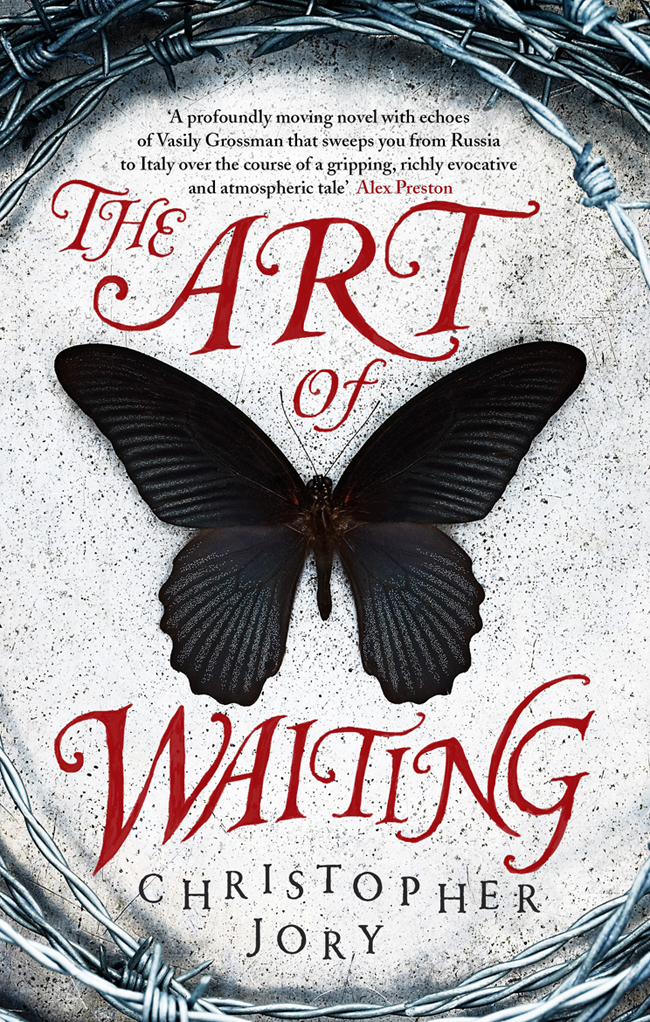

Aldo Gardini stood behind barbed wire in the pale light of a Russian dawn, three hundred miles south-east of Moscow, the start of another desperate day as a prisoner of war. An insect â something small and dark, a butterfly or a moth â had perched itself on the wire a few feet away, its wings lifting up in the breeze. He looked at it longingly as it flew away, then rubbed his hands together for warmth, trying to get some life back into them after another freezing night spent down in his bunker. Tambov 188 had never been intended for human habitation, but needs must â there were just too many prisoners to know what to do with, so anywhere would do and who cared if they died. The prisoners slept underground, each bunker fifteen metres long, fifty men to each one, different nationalities all mixed in together â but Aldo would tell anyone who would listen that they had only one thing in common: they were all Stalin's enemies and all their leaders were stupid enough to think they could invade the Soviet Union and get away with it.

The roofs of the bunkers were made of branches and packed earth and the walls were solid concrete. There was no light and no ventilation, and when Aldo lay there at the end of each day and looked up into the pitch black, he felt as if he had been buried alive. The nights were hell â the cold and the damp, the lice, the jabbering of the men who had gone mad, the stink of the ones who were dying. Typhus did for most of them, a rampant epidemic, and in the morning you'd often wake up next to a dead man. That got the day off to a bad start, and it usually went downhill from there. Up at six, the door flung open by the guards, banging on it with hammers as they did so, shouting at you to get up, total darkness outside, a blast

of cold air blowing in. Your first job was to separate the dead from the living. Farm carts and sleds pulled by mules trawled from bunker to bunker and you loaded the bodies on and took the cart out into the woods that encircled the camp. You'd light a huge fire to soften the ground six feet down, where the spring hadn't yet thawed it out, and then you'd dig a pit and throw them all in. Once you'd sorted out the dead, it was time to wash out the bunker, slopping it out like a barn. Then everyone would troop out into the cold and you'd strip so the guards could inspect you for lice. They dragged this out longer than necessary, of course, watching you shiver, and by the time you got your clothes on again, you were lucky if you ever warmed up. Then off you'd go to spend the day hard at work, as if you still had any strength left in you at all. Then back to the camp, a bowl of soup, something indescribable, a few grains of wheat at the bottom of it if you were lucky. Then an hour of ârest' â political indoctrination â with some bastard in a uniform berating you for something you didn't believe in anyway, when all you wanted to do was sleep. Then finally back to your bunker, where you lay down in the dark at last and prayed.

Today's lice-checking routine had just finished. Aldo had flung on his clothes and was standing by the wire, waiting for the shouting to begin again, the order to set off for work. He thrust his hands into his pockets and rubbed his fingers against the little wooden fish he had carved for himself out of oak at the boatyard back in Venice a year or two before â a little piece of home, a good-luck charm he had carried with him through the war. He listened to the sounds of the camp around him, the dull buzz of deadened voices, thousands of them, as the prisoners gathered to wait for whatever miseries the day had in store for them. A plane flew in overhead, the first of the day, heading for the landing strip somewhere out of sight among the trees. Aldo often wondered who on earth was flying in. Who the hell would want to come here?

The noise of the plane faded and Aldo heard the sound of a beating going on behind him. It was a bit early in the day for a beating, he thought, especially one as bad as this one sounded. It was

a bad sign â the sooner they started, the more they got a taste for it, and that was just the guards. Some of the other prisoners were almost as bad â Romanians, Hungarians, Croats, a few Germans thrown in for good measure, including some that were probably SS. And the thousands of Italians, of course, peasants and manual workers by and large before the war â at least Aldo could understand them, knew what made them tick, knew they would wish him no harm. The thumping stopped and he turned to look. The guards were dragging a body away by its feet. A group of prisoners stood by and watched. Then one of them â a Romanian, judging by the uniform, what was left of it â broke away from the pack, hands in pockets, slouching along as he followed the body. He caught up with it and let fly with his boot, kicking the man repeatedly in the head. The guards dropped the victim's feet and yelled at the man who'd been doing the kicking. He clearly couldn't understand what they were saying, but Aldo could.

âYou're wasting your fucking time!' they were saying. âYou've killed him already!'

One of the guards fetched a spade. He chucked it at the Romanian.

âYou'd better bury him now, hadn't you? But work starts at eight, so be done by then or we'll put you in the grave with him.'

The man just stood there, so they shouted at him again and pushed him towards the gate and around the edge of the fence to an area of bare ground outside. The man got the message. He took the spade and walked towards the gate, then out of it and around towards Aldo, followed by a guard. Aldo watched as the Romanian started digging. He was digging too slowly. The ground was too hard. He would never get it done in time and the guards knew it. Aldo called out to the man in Italian, warning him that his time was limited, but the man just stared at him and said something that must have been an oath.

Fuck you, then, thought Aldo, I was only trying to help.

He leant into the fence, feeling the barbs against his coat as he let it take his weight, testing its strength, daring the guards to react,

but they ignored him â they usually did, and this only heightened the boredom, the isolation, even among all these thousands. He closed his eyes and tried to remember something good, from the time before the war. How long had he been away from home? Less than a year? And only a few weeks in this camp, after the hellish retreat from the Don. But less than a year had completely changed him, and he could make nothing good come to mind. So he forced his eyes open again and let reality back in. Oh God, he thought, it's still here, all of it, the whole damn lot: the barbed wire, the woods, the camp behind, all its smells and its sounds, and the Romanian in front of him digging grimly at the ground. So, eyes closed again, reach out, now, imagine you are anywhere, anywhere but here. But then the buzz of an insect, homing in on the smell of him.

âFucking bugs,' he muttered, and he opened his eyes and looked at the sleeve of his muddy stinking coat, saw it there, something small and leggy that had blown in off the steppe, coming in to bite at him, to take another piece of him. He slapped at it, flailing, but he failed, the thing lifting up again and buzzing off behind him, then going quiet, setting itself down somewhere he couldn't see, just out of reach. They were cunning like that, he thought, never still unless the winter got them, always on the hunt for another bit of his blood. And there would never be an end to them, too many to count, more born every minute, hatching up all around him now that spring was here, thousands of these fucking Russian bugs. So, eyes closed again now, just the sound of the Romanian and his spade, and the guards shouting at someone behind â but then something else too, something soft and hesitant. Footsteps, right in front of him, and a sound like a breath, then a touch upon his hand, his eyelids snapping open as her hand withdrew its touch.

âI'm so sorry,' she said. âI didn't mean to startle you.'

He looked at her face and into her eyes, and he saw it in them now, that look, the look he had always loved, an unexpected recognition, something hatching up from nothing, as if she already knew him, as if she always had, or perhaps he reminded her of a friend, somebody just like him, someone she had loved. There were people like that,

capable of it â he had known that, back in the old days, before the war, and he remembered it still, despite it all. Suddenly her hand was in her pocket, digging around for something, then pulling it out, a rabbit from a hat for him, a little piece of magic, her small white hand holding a dark piece of bread. And what a trick it was, how it made him feel, how it filled his leaping heart.

âHave this,' she said, twisting her hand between the strands of wire, catching her skin on one of the barbs. Up rose a tiny sphere of blood, red on the white of her hand, like all the red he had seen on the snow in the depths of the winter just past.

âI'm so sorry,' he said, at the sight of the blood, as if he were somehow to blame.

âFor what?' she said, wiping it away. âYou've done nothing wrong.'

The wind carried her words away across the steppe before he could cling to them.

âGo on, take it. It's not exactly fresh, but I'm sure it's better than what you get in there.'

Aldo reached out and took the gift. He lifted it to his lips, bit off a piece of it.

âThank you,' he said at last.

Her lips moved, something uncertain, a kind of smile, as if she had remembered something again but wanted to keep it hidden. Aldo longed to speak, to tell her everything, but no more words would come, so they stood there, the two of them, on the edge of wilderness, and he was suddenly aware of the state of him, embarrassed by it, a feeling he had not known for months, a civilising reminder, almost a politeness, brought on by this girl, this reminder of what life had been, what it should always be, a thing of unexpected kindness.

âI might come and see you again tomorrow,' she said. âIf you want me to?'

âOh,' he said, taken aback. âYes, I would like that very much.'

âGood,' she said. âThen I'll do just that.' She turned to go, then stopped. âYou know, I feel so sorry for you,' she said, then paused. âWell, I'll see you tomorrow.'

âYes,' he said. âYes . . . but . . . what's your name?' Trying to detain her, every moment an unexpected joy now, until she went away.

âI'll tell you that tomorrow.'

âTell me now. In case you don't come back.'

âDon't worry, I will come back.'

âTell me anyway. Please. Just in case.'

She looked at him. âKaterina,' she said.

âWhat a beautiful name,' he said, trying to keep her there with compliments, but she was turning away again. âKaterina, wait!'

She turned again.

âHave this,' he said.

He was holding something in his hand and she reached out and took it. A little wooden fish.

âI carved it myself,' he said. âA long time ago. When I was at home.'

âIt's beautiful,' she said. âI'll treasure it.'

âIt's oak,' he said. âIt'll last forever, and it'll bring you luck.'

âThank you.'

âSomething to remember me by. In case you don't come back.'

âDon't worry,' she said. âI told you I will, and I meant it.'

She turned away again and he watched her all the way down the path, her legs brushing against the grass as she went, and then he lost sight of her among the trees.

He turned his attention back to the Romanian. He was struggling now, only two feet into the ground and time was running out. If only he knew. Aldo shouted at him again, urging him to hurry, but the man just looked at him. Aldo could hear the sounds of the trucks behind as the prisoners were gathering for another long day of backbreaking work. He shouted again, but then there was a rough hand on his shoulder, a guard pulling him away from the fence, shoving him towards one of the trucks. He hauled himself up into it, already exhausted before the day had begun. A whistle blew and the trucks pulled away and as he was passing out through the gate, Aldo looked over to where the Romanian stood digging at the earth beneath the gaze of the guard. Then the guard looked at his watch and raised his rifle. The Romanian stopped digging and

looked at the guard. There was the sound of a shot and the Romanian fell into the semi-dug grave.

Aldo spent the rest of the day chopping logs into bits, lifting the dead weight of his axe time after time, but all the while he thought of Katerina. What on earth had compelled her to come over to him, to risk herself for him? Why him out of all the others in the camp? And anyway, wasn't he the enemy? Shouldn't she be afraid of him? Shouldn't she hate his guts? As he dwelt on what she had done, he allowed himself to dream, that one day the world might be at peace and he and Katerina might meet again after the war, and she would come to visit him at his home in Venice, and he would show the most beautiful person in the world the most beautiful city that had ever existed. And they would be together there forever, that's how it would be.

He was still thinking of her late that night as he lay on the concrete floor of the bunker and listened to men all around him tormented in their sleep. And as he wondered if she really would come back to see him again, he was suddenly aware of it, that feeling again, something he had forgotten, something lighting up in him, something she had lit in him.

It was hope.

And he loved her for it.