The Articulate Mammal (46 page)

Read The Articulate Mammal Online

Authors: Jean Aitchison

We possibly start by picking

one

key verb or noun, and then build the syntax around it. Later we slot other words into the remaining gaps.

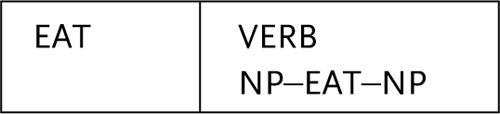

If one key word triggers off the syntax, then we must assume that words in storage are clearly marked with their word class or part of speech (e.g. noun, verb) as well as with information about the constructions they can enter into. For example:

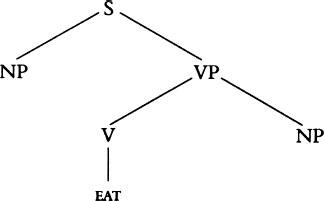

We are, therefore, hypothesizing that when people plan utterances they mentally set up syntactic trees which are built around selected key words:

A key word can be used in planning before it has acquired its phonetic form. This is indicated by slips of the tongue such as:

WHEN IS IT GOING TO BE RECOVERED BY?

In this sentence the syntax was picked for ‘mend’, but the phonetic form activated was RECOVERED. The ‘word idea’ or

lemma

here is not just an intangible ‘concept’, but a definite and firmly packaged lexical item. The useful, and now widely used term

lemma

has been borrowed from lexicographers (dictionary writers) who have for a long time used it for a ‘dictionary entry’. It includes both an understanding of what is being referred to and a firm word class label (verb), as well as (perhaps) information about the syntactic configurations it can enter into. Throughout this outline stage, sentence plans are flexible and can be altered (Ferreira 1996). Outline and detailed planning partly overlap.

By the detailed planning stage, at least some major lexical and syntactic choices have been firmly made. The items already chosen now have to be correctly assembled. Lexical items have to be put into their correct slots in the sentence. This has been wrongly carried out in:

IT’S BAD TO HAVE TOO MUCH BLOOD IN THE ALCOHOL STREAM (It’s bad to have too much alcohol in the blood stream).

A FIFTY-POUND DOG OF BAG FOOD (A fifty-pound bag of dog food).

The slotting in of lexical items must also include fitting in negatives, since these can get disturbed, as in:

IT’S THE KIND OF FURNITURE I NEVER SAID I’D HAVE (It’s the kind of furniture I said I’d never have).

I DISREGARD THIS AS PRECISE (I regard this as imprecise).

Another type of detailed planning involves adding on word endings in the appropriate place (Garrett 1988). This has been done incorrectly in:

SHE WASH UPPED THE DISHES (She washed up the dishes).

SHE COME BACKS TOMORROW (She comes back tomorrow).

HE BECAME MENTALIER UNHEALTHY (He became mentally unhealthier).

However, we can say rather more about the assemblage of words and endings than the vague comment that they are ‘slotted together’. We noted in

Chapter 3

that speakers seem to have an internal neural ‘pacemaker’ – a

biological ‘beat’ which helps them to integrate and organize their utterances, and that this pacemaker may utilize the syllable as a basic unit. If we look more carefully, we find that syllables are organized into

feet

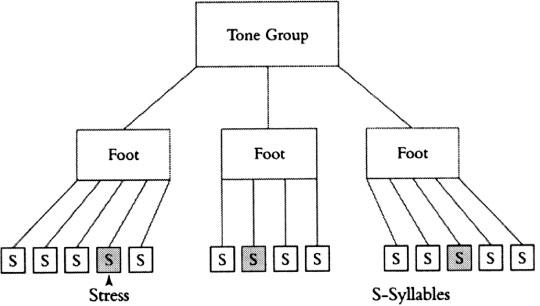

– a foot being a unit which includes a ‘strong’ or stressed syllable. And feet are organized into tone groups. In other words, we have a hierarchy of rhythmic units: tone groups made up of feet, and feet made up of syllables:

So within each tone group an utterance is planned foot by foot. This is indicated by the fact that transposed words are normally similarly stressed, and occupy similar places in their respective feet. For example:

HE FOUND A WÍFE FOR HIS JÓB (He found a job for his wife).

THE QUÁKE CAUSED EXTENSIVE VÁLLEY IN THE DÁMAGE (The quake caused extensive damage in the valley).

Within each foot, the stressed or ‘tonic’ word may be activated first, since tonic words are statistically more likely to be involved in tongue slips than unstressed ones (Boomer and Laver 1968). Moreover, the importance of the syllable as a ‘psychologically real’ unit is shown by the fact that tongue slips ‘obey a structural law with regard to syllable place’. That is, the initial sound of a syllable will affect another initial sound, a final sound will affect another final, and vowels affect vowels, as in:

JAWFULLY LOINED (lawfully joined).

HASS OR GRASH (hash or grass).

BUD BEGS (bed bugs).

According to one theory, sound misplacements like those above occur because a ‘scan-copying’ mechanism has gone wrong (Shattuck-Hufnagel 1979). Supposedly, words already selected for utterance are kept chalked up on a mental blackboard, waiting to be used. A scanning device copies each word segment across into its correct place, then wipes it off the blackboard. In an error such as LOWING THE MORN (mowing the lawn) the L in LAWN was mistakenly copied across to the beginning of the wrong word, and wiped away. The remaining M was then copied on to the only available wordbeginning. In a repetition error, such as CHEW CHEW (two) TABLETS, the speaker forgot to wipe CH off the board after copying it.

As in CHEW CHEW, misplaced segments end up forming real though inappropriate words more often than one would expect from chance (Motley 1985). HOLED AND SEALED (soled and heeled), BEEF NEEDLE (noodle) SOUP, MORE THAN YOUR WIFE’S (life’s) WORTH are further examples of this tendency. This is possible evidence of the existence of a monitoring device which double-checks the final result to see if it is plausible. An overhasty check has perhaps allowed these real words through.

The general picture of speech production is of practised behaviour performed in a great hurry, such a hurry that the speaker does not have time to check the details in full. Just as in the comprehension of speech, listeners employ perceptual strategies (short cuts which enable them to jump to conclusions about what they are hearing), so in the production of speech, production strategies are possibly utilized. A speaker does not have time to check each segment of the word in detail, but may make use of a monitoring device to stop the utterance of too many inappropriate words. If, however, a word happens to be superficially plausible, it is likely to pass the monitoring device and be uttered.

Let us recapitulate: at the outline planning stage, the key words, syntax, and intonation of the tone group as a whole are set up. At the detailed planning stage, words and endings are slotted in foot by foot, with the stressed word in each foot possibly activated first. Finally, the remaining unstressed syllables are assembled – though all these stages overlap partially. The next stage starts before the previous one is finished.

Where does all this leave us? We are gradually assembling information, and testing hypotheses. More importantly, psycholinguists have realized the need for a model which ties everything together. Such models are under continuous development, and these days computers are an essential tool. They allow one to specify components precisely, and to test their interactions. A promising model is one known as WEAVER, which is an acronym (word formed from initial letters) of ‘Word-form Encoding by Activation and VERification’ (Roelofs 1997, 2005). There are still gaps in our knowledge, and much of what we have said is hypothetical. We have realized that, for every clause

uttered, a human speaker must be carrying out a number of complex overlapping tasks. The question of how all this is fitted together still needs further clarification. Perhaps, as an epilogue to the problems of speech planning and production, we can quote the words of a character in Oscar Wilde’s play

The Importance of Being Earnest

, who commented that ‘Truth is never pure, and rarely simple.’

12

____________________________

BANKER’S CLERK OR HIPPOPOTAMUS?

The future

He thought he saw a Banker’s Clerk

Descending from a bus:

He looked again, and found it was

A Hippopotamus.

Lewis Carroll,

Sylvie and Bruno

Psycholinguistics is, as this book has shown, a field of study riddled with controversies. Frequently, apparently simple data can be interpreted in totally different ways. Psycholinguists often find themselves in the same situation as the Lewis Carroll character who is not sure whether he is looking at a banker’s clerk or a hippopotamus.

In this general situation, it would be over-optimistic to predict the future with any confidence. However, certain lines of inquiry have emerged as important. Perhaps a useful way to summarize them is to outline briefly the conclusions we have reached so far, and show the issues which arise from them.

GENERAL CONCLUSIONS

Three psycholinguistic topics were singled out in the Introduction as particularly important: the acquisition question, the relationship of linguistic knowledge to language usage, and the comprehension and production of speech – and these areas were the principal concerns of this book.

In

Chapter 1

, the age-old nurture versus nature controversy was outlined. Is language a skill which humans learn, such as knitting? Or is it natural phenomenon, such as walking or sexual activity? Skinner’s (1957) attempt to explain language as similar to the bar-pressing antics of rats was a dismal failure, as Chomsky showed. Chomsky proposed instead that the human species is pre-programmed for language. This claim was examined in the next few chapters.

In

Chapter 2

, human language and animal communication were compared. Some features of human language were found to be shared with some animal communication systems, but no animal system possessed them all. Attempts to teach sign and symbol systems to non-human apes were described: after a lot of effort, these apes could cope with some of the rudimentary characteristics of human language, but their achievements were far inferior to those of human children. Above all, intention reading and pattern finding seemed to be beyond the ability range of non-humans.

In

Chapter 3

, the hard biological evidence was discussed: the human brain, teeth, tongue and vocal cords have been adapted to the needs of speech. In addition, talking requires the synchronization of so many different operations, humans seem to be ‘set’ to cope with this task.

In

Chapter 4

, Lenneberg’s claim (1967) that language is biologically controlled behaviour was examined. Language fits into this category of behaviour: it emerges when the individual reaches a certain level of maturation, then develops at its own natural pace, following a predictable sequence of milestones. In modern terminology, the behaviour is innately guided. This makes the nature versus nurture debate unnecessary: nature triggers the behaviour, and lays down the framework, but careful nurturing is required for it to reach its full potential.