The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (10 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

The name came rather easily and quickly. Just as Maytag had the “since 1896” on the Anchor label, McAuliffe decided on a little historical alchemy of his own. English explorer Francis Drake combed what would become the Northern California coast in the 1570s, claiming the area for Queen Elizabeth I as Nova Albion (or “New England,” Albion being an ancient name for the British Isles). As McAuliffe would tell the beer writer John Holl, “History is important in the brewing industryâbut, if you don't have a history you can just make it up.” And so he did: Drake's ship, the Golden Hind, would stare out from the New Albion label, with the California coastline in the background and N

EW ALBION BREWING COMPANY/SONOMA, CALIFORNIA

above it. Historyâand, by association, traditionâwould be paired with a sense of place.

As for the know-how, McAuliffe headed about an hour northeastward to see Michael Lewis at UC-Davis. McAuliffe had a homebrewer's understanding of brewing; that is, he knew how beer was made and what could ruin it as well as improve it. But he knew all this only on a smaller scale; it was one thing to make five gallons on a kitchen stove, it was another entirely to make several times that amount, over and over, and have it taste the same each time. Lewis found in McAuliffe “a vacuum cleaner of information,” and McAuliffe in particular made a beeline to the older books on brewing in Lewis's library, some from the nineteenth century. Lewis's program would also be instrumental in advising McAuliffe on the all-important yeast strains that would give New Albion's porters, stouts, and pale ales their flavors.

The old brewing books also provided McAuliffe a template for building the brewery in the old fruit warehouse. It is difficult for us today to imagine the odds McAuliffe and his crew faced, but nothing illustrates them better than the effort involved in fabricating New Albion's equipment and the physicality of the brewhouse. With limited funds and the knowledge going in that New Albion's production would not be that voluminous, at least not at first, the charming copper kettles of European breweries or smaller American operations were out of the question; and the large, industrial-size equipment of Big Beer was pointless. So McAuliffe went foraging. He took special

advantage of Northern California's contracting dairy industry and salvaged a lot of discarded milking equipment. His biggest score came when PepsiCoâironically enough, the spurned suitor of Miller five years beforeâdecided to stop shipping syrup in fifty-five-gallon drums; McAuliffe got hold of several, bending and welding the drums into a mash tun, a brew kettle, four primary fermenters, and ten secondary fermenters.

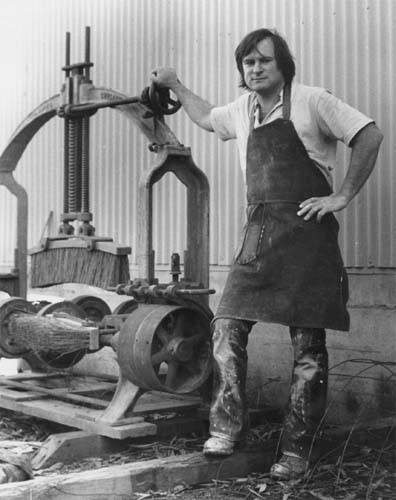

Jack McAuliffe next to an old-fashioned barrel cleaner outside New Albion. He got it cheapâfor about fifty dollarsâand made it work himself.

COPYRIGHT © MICHAEL E.MILLER AND JACK MCAULIFFE

Once he assembled the equipment (or at least located it) over those nine months, McAuliffe set about building the brewhouse within the warehouse, with Stern and Zimmerman helping. It was lonely, long work in the countryside quietude. McAuliffe designed the brewery with gravity as the main power source (there were no pumps at first), setting the starting point of the brewing process on the roof. Hot water would flow from there into the mash tun (the vessel for mixing the cracked malted barley with the hot water to produce wort), then to the brew kettle so the hops and whatever other ingredients could be added, and then from there to primary and secondary fermenters on a lower level, where the wort could be cooled and the yeast added. Finally, it would move to the cellar for aging the wort-turned-beer. When you walked in, you found yourself in a small office with a coal-burning furnace, and a bottling line took up the middle of the brewhouse. The fermentation room was the size of a walk-in closet. There was a laboratory as well, with framed photos of physics and chemistry giants like Einstein, Oppenheimer, and the revered Pasteur. Finally, well above it all was Jack McAuliffe. He had fabricated an apartment for himself over the brewhouse, which he reached by ladder and where he bunked “like a spider,” with a self-made stove and shower. The founder of America's first start-up craft brewery lived literally above the shop.

New Albion Brewing Company filed for incorporation with the State of California on October 8, 1976. Almost exactly seven months later, on Saturday, May 7, at 3 P

M,

the company hosted “the Consecration of the New Albion Brewery,” with an after-party nearby. It would prove to be rare time off. McAuliffe, Stern, and Zimmerman were working ten to twelve hours daily, six to seven days a week, to produce a barrel and a half, or roughly 495 bottles, at a time. And, despite a marketing pamphlet in which McAuliffe welcomed visitors so long as “you telephone me a day or two before,” the pilgrimages started soon after.

*

The full building address was 20330 Eighth Street East.

London | 1976-1977

A

s McAuliffe built beer history

in Sonoma, California, Michael Jackson was giving it a lexicon seven thousand miles away. Born and raised in a

working-class household near Leeds in West Yorkshire in northern England, Jackson had his first beer, a lower-alcohol mild, at fifteen at the Castle Hill Hotel in Huddersfield. He dropped out of high school a year later, in 1958, to support his family, working newspaper and magazine jobs into the late 1960s, when he also worked as a documentary producer and a program editor for British TV host David Frost. In 1969, he was covering a carnival near the Dutch-Belgian border as part of a long gig in the Netherlands that took him away from his London home. There he tasted an ale brewed within the walls of a Trappist monastery in Belgium and found it was nothing like the English beers he had been drinking since his teens. Struck by its complexity and intrigued by its history, the next day he rode the bus less than a mile and a half and, as beer writer Jay Brooks put it, “crossed the borderâhis Rubiconâand began exploring Belgium's beers and culture.”

What Germany and the Czech Republic are to lagers, Belgium is to ales. For a variety of reasons, including a sixteenth-century German dictate that beer be made only with water, hops, and barley (they didn't know about yeast's role then), the South Carolina-sized kingdom has long boasted a rich, complex tableau of ales, from those dark as the chocolate they taste like to ones as effervescent and fruity as any sparkling wine. Brewers there, unlike in Germany, felt free to experiment boldly, often using the hops indigenous to Belgium, especially its northern region of Flanders. Belgium indisputably made the world's most interesting ales. So it was no surprise that Jackson was smitten by Belgian beer. That the experience propelled him to become the most famous and influential beer writer everâperhaps the most influential food writer on any one subject of the twentieth centuryâwas almost as improbable as Jack McAuliffe birthing a brewery by hand in the hinterlands of a small town on the western fringe of the American empire. But that's what happened.

In the same year McAuliffe began building New Albion, Jackson took over the writing and editing of a guide to English pubs when the original author balked. The slim volume allowed him his first stabs at lengthy beer writing. His pièce de résistance emerged the following year, when his

The World Guide to Beer

was released on both sides of the Atlantic by niche publishers.

*

It boomed across 255 pages of photos and fine print, detailing in plain yet densely packed prose the genesis and provenance of hundreds of brands covering myriad styles, from not just the Northern Europe that had captured his

fancy the decade before and that dominated world beer, but also to far-flung locales in the Caribbean and the South Pacific.

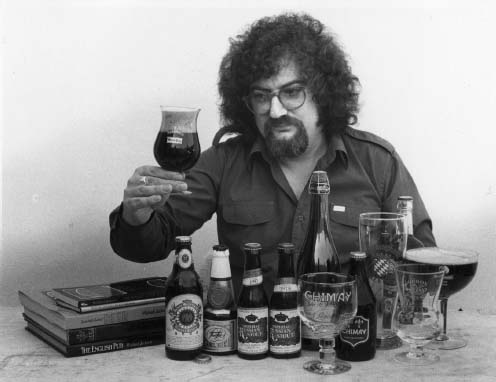

Michael Jackson in a publicity photo for his book

The World Guide to Beer.

COURTESY OF RUNNING PRESS, AN IMPRINT OF THE PERSEUS BOOK GROUP

Beer in the twentieth century had its piper. Never again would budding brewers, critics, and connoisseurs be without a roadmap. Charles Finkel, the wine merchant who would in 1978 begin pioneering the importation of fine European beers to the United States, including many from Belgium, told the beer writer Stan Hieronymus that

The World Guide to Beer

“was to me like a heathen discovering the Bible. It answered all those questions that I had about top and bottom fermentation, about hops, about yeast, about the nature of beer and the history of beer, and traditions of beer and beer culture.” British beer writer Martyn Cornell put it this way:

[Jackson] invented the expression âbeer style,' which was found nowhere before

The World Guide to Beer

appeared, forcing brewers and drinkers to think about the drink in a way they never had before, when they talked merely of âvarieties' or âtypes' of beer. He introduced drinkers to beers they would probably never have heard of without

his work, and he encouraged brewers, directly or indirectly, both to revive old styles and to push the envelope until, sometimes, it tore in their efforts to come up with new styles.”

Jackson's coverage of American beer ran to fourteen pages, three of them full-page illustrations or photographs (Maryland-sized Denmark got ten). A certain melancholy infused much of that coverage. After noting in the first paragraph that “there are single breweries in the United States which produce as much beer as entire European countries,” he took the reader rather quickly through the sad decline of centuries of brewing tradition.

Biggest can also mean fewest. For all its great output, the United States has little more than 50 brewing companies, owning less than 100 breweries. Some of these breweries use a great many labels, but few of them produce more than three or four beers. Nor is biggest necessarily best.

Jackson laid the blame for homogeneity squarely at the feet of Prohibition. He did, however, choose to end his American section on a positive, prescient note, alerting his flowering band of followers to the little brewhouse on Eighth Street.

No beers in the United States are more idiosyncratic than those produced by the Anchor Steam Brewing Company [sic] of San Franciscoâ¦. The smallest brewery in the United States has added a whole new dimension to American brewing.

It would be several years before this most important book on beer in the English language, updated and expanded, with several more pages on American beer, would be a commercial success among enthusiasts in the United States (for one thing, no major American newspaper or magazine appears to have reviewed the 1977 first edition). But people like Cornell and Finkel realized the potential that the book's exhaustiveness offered. Beers could be assessed, using the histories of their styles, as officiously and as vibrantly as wines or spiritsâand by third parties independent of the breweries that created them. (Robert Parker Jr., a lawyer in suburban Baltimore, was doing much the same for wine through bimonthly newsletters launched in 1978.) Jackson had reached back, past the middle decades of the twentieth century, to pull beer from the depths of homogeneity and, in many cases, obscurity. He

launched a revolution in thinking about beer, and it would eventually join the revolution in making beer that was under way in Northern California.