The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (19 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

It was this modesty that especially defined Reich's plan as a craft brewery, rather than, say, just a clever way to create another brand for a regional brewery (Big Beer did not even enter the equation). Where a regional like F. X. Matt might produce five thousand barrels per day, Reich was aiming for much less than that per month and giving himself years to get there; and, unlike many regionals at the time, Reich's beer was to be brewed with traditional ingredients only, no adjuncts, and sold solely in draft or bottles. This traditional brewing approach and the modest production goals set the tone for every contract craft brewer that came afterwardâfor a time, anyway.

Reich rented a warehouse in Manhattan's Meatpacking District, hired two guys to drive the delivery truck as well as a salesman with a background in wine, and, along with him, started marketing the bottles in October 1982 to Manhattan restaurants under the New Amsterdam brand. It was much the same approach as Fritz Maytag had taken going door-to-door in San Francisco more than fifteen years before, and like then, it was a tough sell. The amber lager defied categorization in New York. It wasn't premium, super-premium, or import; it was something different. This was a Manhattan, too, that was still years from the specialty food stores and farmers markets full of locally grown produce, artisanal cheeses, and wines made from grapes pressed on Long Island that would change the conception of grocery shopping in the city. Plus New Amsterdam was more expensive, about twice as much as a bottle of Bud. Reich's pitch was simple yet meant to be game changing: try it. Try it, he would tell skeptical bar owners and restaurateurs. Sure it costs more, but you drink less; it's the antidote to light beer. As for the name, it was taken from the Dutch moniker for what the English would redub New York. Reich had followed a path hewed by Jack McAuliffe at New Albion, though he was not familiar with that brand's backstory.

There was little that McAuliffe might have been able to really teach Reich. That was because, with the birth of contract brewing, the nature of the American craft beer movement was changing. It was moving away forever from the archetype set by McAuliffe, de Bakker, the founders of Boulder, Grossman and Camusi at Sierra Nevada, even Maytag in his original primitive Eighth Street spot in SoMa. Then a craft brewer needed to know not only what ingredients to get for a certain recipe but also how to scrounge for material, how to weld it into something usable, how to position it in a system that would produce beer born from that recipeâall of this in the end requiring at least a passing knowledge of biochemistry and microbiology. It would be years before a craft brewery seemed even remotely like a sure investment of such time and money. But newcomers like Reich now had shoulders to stand on, and contract brewing solved the Sisyphean challenge of capital. (Reich even

looked

different from

these other pioneers. Whereas many of them were given to beards and shaggy miens, never mind blue jeans and sneakers, Reich was clean-cut and cleanshaven, comfortable with suits and in boardrooms; his closest sartorial kinsman in the movement might have been Fritz Maytag, who, though surrounded for decades now by easy-breezy San Francisco, still wore a tie to the Anchor Brewery and kept his hair trim.)

Whatever the fate of contract brewing, others were still trying the old-fashioned way, albeit with readier access to material than Jack McAuliffe had ever had. A couple of hours' drive up the Hudson River from Reich's dream, a budget analyst for the state of New York, William S. Newman, was opening the first stand-alone craft brewery in the eastern United States with his wife, Marie. Tall and lanky, with owlish glasses and shaggy hair parted slightly off-center, Newman had actually filed incorporation papers with the state as early as October 1979âalmost a year to the day, in fact, since President Carter signed the legislation legalizing homebrewing federally. Newman was beyond that stage by the time his Wm. S. Newman Brewing Company opened in an old warehouse in Albany's industrial district with an annual capacity of five thousand barrels (though it would at first produce half that). He had apprenticed at the Ringwood Brewery in southern England, bringing back a taste for that country's pub culture and its milder ales. Newman's pale ale debuted in February 1982, described in the

New York Times

with quotation marks around the adjective “hopped.” He insisted at first that local establishments serve this and subsequent beers warm, at about fifty degrees Fahrenheit, in the English style, which the vendors were not always happy to do. Newman realized this insistence was a problem for the all-draft operation when an amber ale he brewed, which was meant to be served cold, began to outsell the pale ale. “Americans like their beer cold,” he concluded. Newman sprung into action in 1983, acquiring a bottling line and tweaking the pale ale recipe a bit to make it acceptable for serving at cooler temperatures (thirty-seven to forty degrees). He rolled out the East's first specialty craft beer since Prohibition, Winter Warmer, in 1983, a brown ale of nearly 6 percent alcohol per volume that he compared to a Guinness-like stout, though not as bitter.

Further down the East Coast, in the Virginia Tidewater, an orthodontist and a veterinarian, both in their mid-thirties, were putting the finishing touches on what would become the first craft brewery in the South. Jim Kollar, a Penn State linebacker turned veterinarian, had been homebrewing since before the federal law change, creating increasingly larger batches until he and his friend Lou Perrin, the orthodontist, decided to make the commercial leap with a few other investors, all relatives, and a brewmaster hired from West

Germany. They were prepared to put up as much as $250,000 to make the Chesapeake Bay Brewing Company work from the ground up at an old industrial park in Virginia Beach. That would allow them to produce twenty-five hundred cases a week eventually of a signature amber lager they planned to brew using Cascade hops. As Perrin told a reporter in the winter of 1982 as he poured cement at the brewery site, those expecting a “locally brewed Budweiser” would be disappointed. “It will be made from only malt, hops, yeast, and water,” he said. “That means no corn syrup, no corn flakes.”

William Newman in his brewery in downtown Albany.

COURTESY OF CHARLIE PAPAZIAN

Back West, more California craft breweries were in start-up mode. Jim Schlueter ran across Michael Lewis's brewing curriculum while browsing the course catalog as an aimless freshman at UC-Davis. He earned a degree in that curriculum and went to work in Wisconsin for Schlitz, then one of the biggest breweries in the country. Wanting, however, to “brew beer by tongue rather than by computer,” he cobbled together $350,000 in loans and started the River City Brewing Company in an old upholstery shop in downtown Sacramento, California. It was the first American craft brewery to focus on lagers rather than ales. In Mountain View, California, amid the microchips and venture capitalists of Silicon Valley, a father and son were using what they saw working in the burgeoning computer industry in the making and marketing of craft beer. Kenneth Kolence had in 1967 cofounded Boole & Babbage Inc., one of the world's first computer software concerns. His son Jeffrey had written

his senior paper at California Polytechnic on the operations and layouts of small breweries and the mistakes they made in both. The younger Kolence then spent six weeks studying at a small brewery in England while his father raised $400,000. By the end of 1983, their Palo Alto Brewing Company was selling ten to fifteen barrels a week of their flagship London Real Ale, a bitter, to a half-dozen or so bars in San Mateo and Santa Clara Counties south of San Francisco for $2 to $2.40 a pop. Nearby, in Berkeley, another family brewery, albeit on a smaller scale, was inching forward. Charles Ricksform started brewing small batches of ale in his basement in 1981, with his two sons and a daughter, under the name Thousand Oaks Brewing Company.

Also in California, the nation's second and third brewpubs, after Bert Grant's in Yakima, Washington, were opening. (Governor Jerry Brown had signed legislation in 1977 that allowed for on-premises sales of beer up to certain amounts, removing the sort of legal ambiguity that would continue to haunt brewpubs and would-be brewpubs in other states.) That third brewpub belonged to Bill Owens, a slender photojournalist with a shock of thick salt-and-pepper hair, who homebrewed so much that, on his fortieth birthday in 1978, a friend suggested they start a brewery. Owens went to his accountant and asked how one raised money these days. The accountant reached into his desk drawer and pulled out a form meant for another client. “White out âalmond farm' and put in âbrewery,'” he said, explaining a limited partnership.

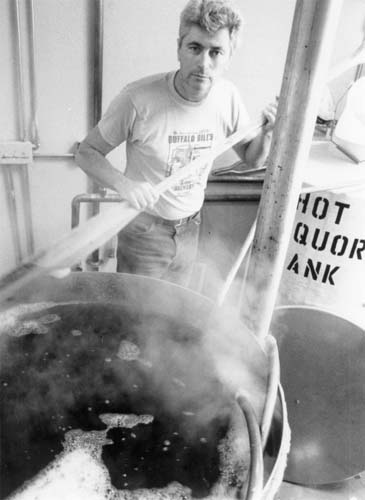

Owens rented an old camera store in downtown Hayward, southeast of San Francisco, and renovated it using about $90,000 he raised through selling thirty-three shares through the limited partnership. The equipment came in the usual way: from a candy company, a food manufacturer, and, of course, a dairy, with sixty-two feet of pipe laid from the brewhouse to the bar with the help of an investor who normally worked on nuclear bombs. The brewhouse was visible through a picture window that allowed the customers up front to see where the beer they were drinking was coming from. Buffalo Bill's Brewpub opened on September 9, 1983, with annual production reaching about three hundred barrels. As Owens told the writer William Least Heat-Moon a few years after opening, the money came in the ingredients-to-sales ratio, something that would hold true for other brewpubs nationwide. “For $130 worth of ingredients, I can make a $2,500 profit,” Owens explained. “A glass of lagerâthat's all I brew nowâcosts seven cents. I sell it for a dollar and a half. Compare my profit on a bottle of commercial beerâforty cents.”

Bill Owens in the summer of 1985 in his Buffalo Bill's Brewpub in Hayward, California.

COURTESY OF BILL OWENS

One hundred and twenty miles to the north, California's oldest brewpub had already been under way for a month by September 1983 in the impossibly appropriate town of Hopland. It also claimed remarkable parentage: the

start-up equipment for the Mendocino Brewing Company came from Jack McAuliffe's New Albion. So did its first brewmaster, Don Barkley. It was the founders and first employees of Mendocino that did McAuliffe the grim favor of absorbing the equipment he had fabricated when the old fruit warehouse in Sonoma had to be vacated. McAuliffe went with it, for a whileâhe left the

new brewpub pretty soon after arriving, and then he left the craft beer movement altogether. Barkley, along with Mike Lovett, another old New Albion hand, and the company's three founders, Michael Laybourn, Norman Franks, and John Scahill, quickly built Mendocino's Hopland Brewery, Tavern, Beer Garden, and Restaurant into a success. They were soon brewing 120 cases of beer a week on the old New Albion equipment, and it was selling out in as little as three days, all out of this novel thing called a brewpub. The location didn't hurt, eitherâninety miles north of San Francisco, off one of the nation's busiest highways, 101.

Farther north, in Oregon, two vintners were picking up where two other vintners had left off. Dick and Nancy Ponzi owned Ponzi Vineyards near Portland, and they hired a native of the area, Karl Ockert, an avid homebrewer fresh out of Michael Lewis's program at UC-Davis, to fashion the first craft brewery in Oregon since the Courys' Cartwright Portland closed in 1982. The Columbia River Brewery brewed its first beers, ones more on the malty than the prevailing hoppy side, in late 1984 in an old, three-story cordage factory in Portland's industrial northwest. With an annual capacity at first of six hundred barrels, it was eventually renamed the BridgePort Brewing Company.

On the same unremarkably grungy side of the Willamette River, two brothers in their twenties who learned homebrewing from an uncle were pushing toward their own brewery, unhappy with the commercially available beers in Portland. Kurt and Rob Widmer had drawn up a business plan that set as a goal twenty draft-beer accounts. They quickly surpassed that after their April 1984 opening and came to help define American beers that used wheat instead of barley as the primary grain. Together, BridgePort and Widmerâwith no small help from Portlander Fred Eckhardt, who continued to write regularly about beer in local media and his own publicationsâwould spark not only one of the more significant local craft beer booms but also a renaissance of that area of the city.