The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution (36 page)

Read The Audacity of Hops: The History of America's Craft Beer Revolution Online

Authors: Tom Acitelli

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

While barrels of ink were being spilt upon dead trees on behalf of brewing, breweries, and brewpubs by the mid-1990s, another medium was emerging that would prove infinitely more influential. When it came to craft beer, it would be democratic, dictatorial, illuminating, confusing, accurate to a tee and rife with errors all at the same instantaneous time. At first, it was cumbersome to read and nothing much to look atâBill Owens's art would most certainly not work with it. For consumers, there was a considerable barrier to entry, too, compared with the cost of a magazine or even a book. You had to have a computer or at least access to oneâand that computer had to have access to the Internet. Still, for those who mastered it, the new technology provided a fount of fast information and exchange, rendering not only quaint but obsolete those paper newsletters of early homebrewing clubs like the Maltose Falconsâand, for those paying attention, it drew a bead on the print publications.

The first Internet site for the craft beer consumer was started in late 1986 by Rob Gardner out of Fort Collins, Colorado. He set up and ran manually from his computer an e-mail newsletter, called

The Brewsletter,

that would grow by the decade's close into the

Home Brew Digest,

a forum for homebrewers and beer enthusiasts worldwide. Gardner, to keep up with the subscriber

volume, wrote code that could handle routine tasks like dealing with those subscriptions and sending out the digest; it had quickly moved beyond what could be run manually. Most of the subscribers were college students or staff (thus the access to Internet connections). And, difficult as it is to imagine, there were none of the graphical bells and whistles of today's web; the digest was largely an all-text, black-and-white compendium of messages that Gardner had received or that had been e-mailed to the subscriber list. The site's exchanges were also regularly reposted on other early Internet beer forums, like AOL's Food and Drink Network and brewing forums hosted by Prodigy and CompuServe. The exchanges usually followed a question-and-answer format, with someone from Massachusetts, say, sending in a list and someone from New York sending in a correctionâas happened on Halloween of 1988, shortly after 5

PM

Eastern time, when someone from the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York, wrote:

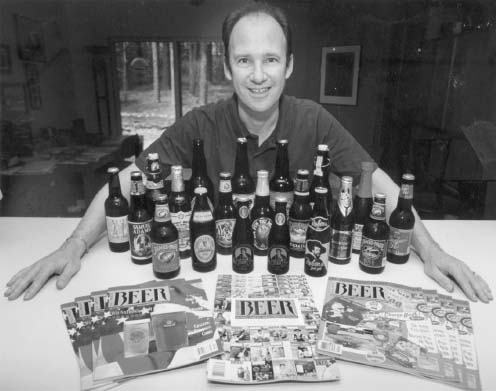

Daniel Bradford in 1994, a couple of years after he and Julie Johnson took control of

All About Beer

magazine.

COPYRIGHT THE DURHAM MORNING-HERALD

co.

USED WITH PERMISSION.

Subject: nice list, changes needed

hey thanks to jmiller for putting together that micro and brewpub list.

Please note that Bill Newman's brewery is now defunct. He contracts

through F. X. Matt in Utica. You stand a better chance of getting a response by writing them. I know I long ago gave up waiting for him to return my calls.

Or this message on Veterans Day of the same year, which showed just how far and wide the movement had reached. It came from someone at Clemson University in South Carolina, which had yet to legalize homebrewing at the state level and which contained no craft breweries as of 1990:

Subject: Ginger Beer/Honey Beer

Does anyone have a recipe for ginger beer or for a honey beer? A friend has recommended that I try both of these, but neither one of us has a recipe. I am fairly new to this hobby, so any general advice would also be appreciated.

*

Owens changed the name from

Amateur Brewer

as both the magazine and the movement became more professionalized.

Kailua-Kona, HI | 1993-1995

A

t the annual Craft Brewers Conference

in Austin, Texas, in April 1995, Charlie Papazian asked the ballroom of attendees how many were planning or wanted to open a brewery but had not yet done so. Most of the people in the ballroom raised their hands. As we have seen, the craft beer movement was growing across the country, making its way into areas that would have seemed commercially inhospitableâor just plain bizarre, as in the case of Geoff and Marcy Larson's Alaskan Brewing Company in Juneau. Another such area: the other noncontiguous state.

Cameron Healy grew up in Bend, a small city in central Oregon. His father, Bill, had moved everyone there in the 1950s to run the family furniture store, but Bill soon turned to a new line of work in the windy taluses of the nearby Willamette National Forest by opening a ski resort. Mount Bachelor became one of the nation's leading ski resorts when it came to technology, with highspeed chairlifts and a computerized ticket system. Cameron Healy worked at the resort until he left Bend to attend the University of Oregon in Eugene. It was there his story became a kind of microcosm of the 1960s. While pursuing

a social sciences major, he took up yoga, converted to Sikhism, and changed his name to Nirbhao Singh Khalsa. In the process, the sleepy-eyed Oregonian, with curly hair running from the top of a prominent forehead to just above his collar, swore off alcohol and simplified his life, tilting it to revolve around the yoga commune. How to help pay for that commune, however, and yet not compromise its back-to-the-earth ethos? Healy invested $1,000 in a bakery called the Golden Temple, which opened in Eugene in 1972, and produced exactly what you might expect: whole grain breads, granola, and other healthy, natural foods of a sort that seemed novel in an America with an increasingly homogenized cuisine.

After a year and a half, Healy donated the bakery to the commune and moved on to his next venture, one as crunchy as the last but savvy. He knew he and his compatriots would age, a wave of baby boomers growing old with ideals and practices picked up in college towns like Eugene throughout the nation. Those practices would need to be serviced and those ideals respected; and both would have to be done in a convenient, uncomplicated way as the baby boomers traded “Get Clean for Gene” pins and George Harrison LPs for bourgeois respectability in car-dependent communities. Healy started a natural food distribution company out of Salem, Oregon, that grew by 1978 into a natural-food manufacturing concern called the N. S. Khalsa Company. The company, which started with a $10,000 bank loan and with Healy selling roasted nuts, trail mixes, and cheeses to outlets along Interstate 5 out of an old van, grew by the late 1980s into one of the most successful natural-food brands in the country. Its signature became the potato chip, and it's through that, unbeknownst to the teetotaling Healy, that his story began to intertwine with the craft beer movement.

Americans loved their potato chips, Healy knew, and, through a wave of consolidations that saw smaller firms gobbled up by larger ones, most were produced through a handful of companies by the 1980s. The largest potato chip producer in the United States, Frito-Lay, was formed by the merger of two different firms and grew to forty-six production plants by the time of its own 1965 merger with Pepsi-Cola to form PepsiCo. While their nineteenth-century predecessors might have been produced by hand one slice at a timeâthe potato chip was said to have been invented by a chef at a Saratoga Springs, New York, resortâthose of the late twentieth century were anything but. The chips produced in Frito-Lay's dozens of plants were deep-fried by the hundreds per minute, laden with trans fats, heavily salted, and sealed in cellophane bags for shipment to all corners of the country. Americans inhaled them; potato chips reigned as the nation's top snack food by the end of the 1980s, with sales

growth twice that of any other. But consumers had little idea of the chips' origins and couldn't care less about what obtuse ingredients preserved them on their journeys to supermarket shelves and vending machines. If I could create a distinctive-enough product, Healy thought, there would be a mystique about them.

He set about in 1982 crafting some more natural potato chip prototypes in his home nut roaster using only Oregon-grown potatoes. The chips found a market: N. S. Khalsa's sales hit $3 million within two years of those first home batches, mostly because of what it called its all-natural potato chips, made with local spuds, no trans fats, and, eventually, all organic ingredients. It was certainly different from what consumers were used to in a snack food, though it was not without its pratfalls. The small batches didn't always work out taste-wise, and Healy's company found itself pulling some bags from shelves because the quality was bad. Gradually they reached the upper end of the manufacturing learning curve, turning out consistently good batches that found their ways first into natural-food stores and then into other retailersâand without having to buy shelf space. The sales of Kettle Foods (the company changed its name in 1988) were largely due to word of mouth, consumers nudging one another about this curious addition to an American staple. The company opened plants in Ohio, Ireland, and England, and, in 1993, it scaled a personal summit for a Healy: revenues beat those of his father Bill's ski resort. Cameron Healy started looking around for something else to do.

Luckily, he had started drinking again. A 1987 trip through northern Europe introduced him to Belgian beers in particular, and he had long been familiar with the American craft beer brands on the West Coast. Here was a whole segment of an industry that seemed to approach its production the same way he had approached the production of potato chips and other foodstuffs since the 1970s; it even had the same mystique about it. Craft beer brands had colorful owners and local foci in their production. Not only that, but also just about every brand, even the contract brewers, chose to anchor their imagery to their localities and to stress the craftsmanship, the natural ingredients, the wholesomeness of their ingredients. Healy started assembling a business plan for a craft brewery. His son, Spoon Khalsa, had the perfect spot: Hawaii's Big Island. Father visited son there over Thanksgiving 1993 to kick the entrepreneurial tires all over again.

The state did have a brewing history that stretched back to the early nineteenth century with the arrival of the first Europeans; but any breweries it had going were wrecked by Prohibition in 1920 as surely as it wrecked breweries on the mainland. A handful of breweries reemerged after Repeal;

the Hawaii Brewing Corporation's new location at Kapiolani Boulevard and Cooke Street in Honolulu, which opened in May 1934, was the first brewery to be completely constructed west of the Rockies post-Prohibition. The brand it produced, Primo, however, became the last one standing in Hawaii by the 1960sâand it was made under the aegis of Chicago-based Schlitz. On May 15, 1979, Schlitz shipped the last cases of Hawaii-brewed Primo and transferred production to a plant in Los Angeles; the moves marked the end of commercial brewing in the state.

Aloysius Klink and Klaus Haberich brought brewing back to Hawaii in the summer of 1986 with their Pacific Brewing Company's Maui Lager, proudly brewed according to the strictures of the German beer purity law, the Reinheitsgebot. Their beer was a hit. The brewery sold more than four thousand barrels annually after its first year, including in California, and garnered regular media attention that could not resist noting the barley, hops, and yeast came from Belgium, Germany, and Canada, while the water was Hawaiian. Still, Pacific Brewing collapsed in late 1990. It seems to have vanished without much of a trace, its closure likely due at least in part to shipping costs, including distribution to and on the mainland.

This was the situation facing Cameron Healy and Spoon Khalsa when they launched the Kona Brewing Company. It was a potential consumer goldmineâResorts! Luaus! Tourists, locals, more tourists!âthough isolated geographically, even more so than the Larsons' Alaskan Brewing Company. Healy saw opportunity in this isolation. Hawaii had no commercial breweries after Pacific Brewing; here was an opportunity to repeat the successful formula of the potato chips: craft on a small scale a foodstuff that can appeal to those looking to pivot away from its mass-produced versions and to enjoy something with local roots. It was a chance to try out the locavore approach with no real competition. Healy believed they had the winds at their back.