The Autograph Man (10 page)

Alex smiled.

“Can I get one from Mountjoy, please.”

Gladys cupped her ear theatrically, International Gesture for

Come again

?

“You waan what? You goin’ Mountjoy?”

“No—no, I just

came

—”

“Bwoy—speak into de ting; me kyan hear you.”

“I said, I just

came

from Mountjoy—”

“So, you want a ticket back dare?”

“No, I—just—the machine at Mount— There was a train coming, so I just jumped—”

“Oh, I see. You can call me Cassandra, young man, ’cos I see, I see.”

“No, look. Right. No. Let’s start again. Wasn’t like that, was like this: I just—there was no time to buy . . . so I . . .”

Alex faded. The woman reached for a long piece of homemade something—two pencils bonded with an elastic band—and slipped it down into her cast. Scratched.

“So, what you are sayin’—and feel free to correct me if I am perchance mistaken—is dat you skipped de fare; you jus’ skip it like it

nutting

—”

“Wasn’t like that—”

“—dareby

ignoring

de executive and legislative decrees of our government—”

“Is this . . . ? I mean—in the wider sense—necess—”

“—not to mention de

explicit

conditions of travel as set out by de London Underground, available for perusal by anyone

wid eyes;

as well as

violatin’

a communal code of fairness and

right doin’s;

as implicitly held by your fellow passengers—”

“Yes, ha. Very good. Look, I’m actually running—”

“—and last, but

by no means least,

making a nonsense of your own personal conscience wid regard to an

imperative morality

which, if we don’t feel it in our bellies, we will find articulated in Exodus: Thou. Shalt. Not.

Steal.

”

Sometimes Alex thought that if you got all the part-time mature students in the world and laid them head to toe around the line of the equator strapped down in some way so they couldn’t move, that would be a good thing. Ditto anyone in night class.

“Ten pounds, please, young man. Wid de fare on top.”

Alex didn’t have ten pounds so he handed over some plastic, which made the woman suck her teeth, lift her leg off the

The Last Days of Socrates

and go hobbling to the back of her box to get the mechanical swiper thing. She swiped, she passed it through, he signed, he passed it through, she held it up next to his card, he smiled. She looked at him with suspicion.

“Is dis yours?”

“What? Is there something wrong with it?”

She looked at the card again, at the signature, at the card, and then passed it back to him.

“I don’t know. Mebbe wid you. You look like you sick or someting. Like you goin’ to fall over.”

“Sorry, Gladys, are you a doctor? Or a prophet? I mean, as well? Or can I go now?”

She scowled. Called for the next person in line. Alex grabbed his flask from the counter. Stalked towards the exit.

OUTSIDE, HE TOOK

a sharp left, intending just to run the length of the street, turn left and walk straight into the auction house. But he had not counted on the sales. On the women. The sun was low enough to spotlight them, they were outlined very precisely. They put Alex in mind of the Chinese shadow puppets of the old Tangshan theater. They moved fast and did not blur. So beautiful! In through doors, setting off tinkling bells, back out, doing it again. Handsome, quick, lithe: deer doing the hunting for a change. There was a chasm between this and the manner in which Alex shopped (a sort of blind lunge from store to store, and only for necessities, toilet paper, toothpaste). These women made desire look efficient. There was nothing in this street they wanted enough to induce any loss of poise. They were amazing.

But I am too late already! thought Alex, looking at his watch. His sweater was mohair; his neck was sweating. Still, how could this be resisted? In preparation, he paused in the middle of the street, took off his trench coat, tied it round his waist. He took a tiny pad out of his pocket and pressed it into his palm, ready to take notes. And then Alex began to walk, slowly, amongst them, splitting them down the center as they went, as he always did, for his hobby, his research, his book. Goyish.

Jewish.

Goyish. Jewish. Goyish.

Goyish.

Jewish.

Goyish!

NOT THEM, NOT

as people—there was no fun to be had out of that. Only wars. No, other things. A movement of an arm. A type of shoe. A yawn. A dress. A whistled tune. It gave him a simple pleasure. Other people wondered why. He chose not to wonder why. All possible psychological, physiological and neurological hypotheses (including the

Mixed-race people see things double

theory and the

fatherless children seek out restored symmetry,

and

especially

the

Chinese brains are hard-wired for yin-and-yang dualistic thought

) made him want to staple his eyeballs to a wall. He did it because he did it. He had an unfinished manuscript that maybe someone would publish one day, called

Jewishness and Goyishness,

the culmination of his work on the subject.

Jewishness and Goyishness

had once been a fairly academic text by any standard. It had an introduction, it had essays and explanations, footnotes, marginalia. (He had imagined it as an appendix, a sequel, if you like, to Max Brod’s effort of 1921,

Heidentum, Christentum, Judentum.

He was also indebted to the popular comedian Lenny Bruce.) It was split into many different categories, things like:

Foods

Clothes

The nineteenth century

Cars

Body parts

The lyrics of

John Lennon

Books

Countries

Journeys

Medicines

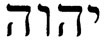

Each category was then split into Jewish and goyish things relating to it. In a spasm of superstition early on, he had made the decision to mark the sections of the book with the Tetragrammaton, God’s fourletter name:

YHWH

Occasionally, when the section was particularly contentious, he used its more potent Hebrew incarnation:

As if the invocation of the Holy Name would protect his heresy.

He had been young, naive, when he began it. It was a different book now. It was still about Jewishness and Goyishness, but now that was

all

it was about. No essay was more than a page in length. There were no captions to the many illustrations. All stripped away. Just a few footnotes here and there. No commentary. Now he was left with the beautiful core of the thing itself: three hundred pages and counting of what amounted to a two-sided list. Jewish books (often not written by Jews), Goyish books (often not written by Goys); Jewish office items (the stapler, the pen holder), Goyish office items (the paper clip, the mouse pad); Jewish trees (sycamore, poplar, beech), Goyish trees (oak, Sitka, horse chestnut); Jewish smells of the seventeenth century (rose oil, sesame, orange zest), Goyish smells of the seventeenth century (sandalwood, walnuts, wet forest floor). And God’s unsayable name on every page. Over and over. The book was a thing of beauty. He did not let people read it. If ever it came up in conversation, he found himself spoken to as if he were a character in a film. Rubinfine told him he was

wasting his life.

Adam

worried for his sanity.

It was Joseph’s opinion that to discuss the book at all was to

indulge the dangerous idea

that the thing actually existed. Esther

found the whole thing utterly offensive.

Well, maybe

Jewishness and Goyishness

wasn’t for everyone. But didn’t everyone get

everything

? Hadn’t they had enough yet? Everything on earth is tailored for this

everyone.

Everyone gets all the TV programs, as near as dammit all of the cinema, and about eighty percent of all music. After that come the secondary mediums of painting and those other visual arts that do not move. These are generally just for

someone,

and although you always hear people moaning that there isn’t enough of them, in truth

someone

does all right. Galleries, museums, basements in Berlin, studio flats, journals, bare walls in urban centers—someone gets what they want and deserve, most of the time. But where are the things that

no one

wants? Every now and then Alex would see or hear something that appeared to be for no one but soon enough turned out to be for someone and, after a certain amount of advertising revenue had been spent, would explode into the world for everyone. Who was left to make stuff for no one? Just Alex. Only he.

Jewishness and Goyishness

was for no one. You could call it the beginning of a new art movement if it weren’t for the sad fact that no one would recognize a new art movement if it came and kicked them in the face. No one was waiting for

Jewishness and Goyishness.

No one wanted it. And it was not finished yet. When it was finished he would know.

FOR A WHILE NOW

, his book had been in crisis. It was lopsided. Goyishness, in all its forms, had become his obsession. There was now too much in it concerning aluminum foil, sofa covers, pushpins, bookmarks, orchards. In the book, as in his life, Jewishness was seeping away. Three months earlier he had attempted his greatest audacity: a chapter devoted to the argument that Judaism itself was the most goyish of monotheisms. He failed spectacularly. He became very depressed. He called his mother, who stopped making things out of clay in Cornwall with Derek (the boyfriend) and returned to London to stay in his flat for a few weeks, to keep an eye. But for Sarah it did not come naturally, this mothering role. That had been Li-Jin’s thing. Her gift was friendship, and Alex, for his part, did not know how to lie back and have soup brought and temperatures taken. Their progress together was awkward, somewhat comic, like the days of two crook-backed adults living in a Wendy house. And all without Li-Jin. The terrible, undimmed sadness of it. Every time they met, they felt it afresh, as if they had planned a picnic, Alex arriving with all the cutlery, Sarah with the mackintosh squares—where was the food?

Still, Alex (who like most young men remained convinced his mother was uncommonly beautiful even as she thickened and grayed) was charmed by her physical presence, her floaty hippie skirts and scarves, her hands which looked like his, the matter-of-fact way she would suddenly hug him to her chest as one man hugs another man on a playing field. She had things to say.

She said, “If I’m anything, darling, I’m probably a Buddhist.”

She said, “You see, when I married your father . . .”

She said, “I think it’s probably important to

do

rather more, and maybe

think

a little less?”

She said, “Where do you keep your cups?”

Before she left, she gave him a box of papers and stuff relating to the relations. “You mean this sort of thing?” she said, placing it on his nightstand.

Sarah Hoffman’s family. Trinkets and photographs and facts. Here was Great-grandfather Hoffman as a young man in European pose, looking cocky, clutching two other young men by the shoulders, the three of them with their thin ties and legs apart, standing in front of some building, some new enterprise, never to be finished. In another, four pretty sisters stand in the snow. Their heads are pitched at various melancholy angles. Only their lean Afghan hound looks at the camera, as if he knows the future secret of their terrible deaths, the location and the order. Elsewhere, a sepia postcard shows Fat Uncle Saul. A studio portrait of him as a boy with palm tree and pith helmet, his sausage legs astride a stuffed miniature pony. This same Saul had believed that the Hoffmans were related to the Kafkas of Prague, through marriage. But what’s marriage? Alex dug deeper. A tram ticket for a defunct line through a defunct city. Ten zlotys. A pair of sloppy socks of scarlet wool with lilac lozenges. The qualification certificates of an émigré Russian teacher, distant cousin. One bowler hat, crushed. But let somebody else make a mournful list, thought Alex. The people who keep boxes like these are the type who follow ominous noises into the dark cellar, who build their very homes on top of Indian burial grounds. People from movies. Everyone in these photographs is dead, thought Alex, wearily. Tiring, all of it.

3.

The night at Adam’s, the night in question, this was not the first time Alex meditated on the letters. He had been going more often in recent months, thinking it might help. The procedure was always the same. They got stoned. They sat on the floor, holding big blank drawing pads. Pens at the ready. Staring at the walls. On the far wall, ten years ago, Adam had painted a crude Kabbalistic diagram, ten circles in strange formation. These were, according to Adam, the ten holy spheres, each containing a divine attribute, one of the

sefirot.

Or else they were the ten branches on the Tree of Life, each showing an aspect of divine power. Or they were the ten names of God, ten ways in which He is made manifest. They were also the ten body parts of Adam, the first man. The Ten Commandments. The ten globes of light from which the world was made. Also known as the ten faces of the king. Also known as the Path of Spheres: