The Baking Answer Book (43 page)

Read The Baking Answer Book Online

Authors: Lauren Chattman

Tags: #Cooking, #Methods, #Baking, #Reference

If you don’t have any interest in science, don’t worry. Remember that yeast breads were being baked well before the invention of the microscope in 1674 and the subsequent discovery of yeast and friendly bacteria called lactobacilli that are responsible for bread’s rise. As far back as 3000 BCE, ancient Egyptians were making leavened bread. How did they discover that the introduction of yeast into the basic flatbread formula of flour and water would result in a light, puffy, and flavorful loaf so much more pleasing than the crackerlike flatbreads baked without yeast? Historians speculate that perhaps it was the accidental discovery that dough left to sit longer than usual before baking would capture wild yeast, which caused it to rise when

baked. Or the discovery might have first been made when a creative baker decided to mix some beer (which contains yeast) into flour along with or instead of water. These early bakers had no idea that microscopic organisms were causing their bread to rise. They only knew that under certain conditions or in the presence of certain ingredients, it would happen. So they learned through experience which ingredients were best for bread and how to be sensitive to bread dough through every step of the process so that it would rise well and taste good.

The questions in this chapter are not all, or even mostly, about science. Equally important in crafting a loaf of bread are experience with and sensitivity to the dough. If you don’t have much experience and have not developed this sensitivity, knowing the answers to questions such as, “How do I know if I’ve kneaded my dough sufficiently?” and, “How do I know if my bread has proofed long enough?” will give you an idea of what to expect and what to look for as you bake.

Q

What is bread flour and should it always be used in bread?

A

The more protein in flour, the more gluten it will develop during mixing and kneading. The more gluten a dough has, the stronger its structure will be and the higher it will rise. While all-purpose flour has a protein content of about 12%, bread flour contains 13% to 14% protein — a much better choice when you are trying to make a dough with a lot of stretchy gluten.

But the choice of flour is actually a complicated one. It makes sense to use bread flour in recipes where a lot of gluten is important. Rye breads, for example, are made from a combination of rye flour, which has no gluten at all, and wheat flour. So the wheat flour used needs to be of the highest strength, since it will be providing all of the gluten for the dough. But a high-gluten flour is not always desirable. Though bread flour may be perfect if you want to make a crusty artisan bread with a very chewy crust and a crumb that’s distinguished by large air bubbles, it may not be quite right if you want to make a softer, more yielding bread like a challah.

Bread recipes will guide you on what flour to choose, but as you become more experienced with bread baking, you might make your own adjustments. Say your pizza dough, made with bread flour, was too tough for your taste. Next time you might try substituting some all-purpose flour for the bread flour to give it a softer texture. Or maybe the sandwich bread you made with all-purpose flour lacked character. Some bread flour next time might give it a thicker crust and a higher rise.

HOW A MIXTURE OF FLOUR, WATER, YEAST, AND SALT BECOMES BREAD

The transformation of a handful of the most basic ingredients into a well-risen, tantalizingly fragrant loaf may seem mysterious, but the science underlying this transformation explains it all. In a nutshell, here is what happens to a lump of dough at different stages in a typical bread recipe.

Kneading.

Mixing together your ingredients and kneading them into a smooth, elastic mass accomplishes several things at once. Mixing distributes yeast and salt evenly throughout the dough, essential for a successful rise. You may not be able to see it happening with yeast, but if you are mixing nuts, seeds, or raisins into your dough you can easily see how this happens on a larger scale. Kneading also introduces oxygen into the dough. Later on, when the dough is rising, oxygen will provide food for the yeast.

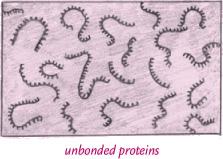

But the primary function of kneading is to develop the gluten in the dough. All wheat flour contains two types of protein, gliaden and glutenin. (See

page 7

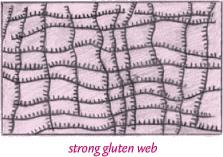

for a comparison of protein content of different types of flour.) Only when these proteins come in contact with water can they bond with each other to form a stretchy, elastic web called gluten. It is this gluten web that will provide structure (like the steel beams that hold up a building) for the bread as it rises.

Once gluten is formed, it must be strengthened through the repeated action of flattening and folding. As you knead your bread, you will feel it transforming from a rough, sticky mass into a smooth, elastic ball. This smoothness is the result of the proteins organizing themselves into a gluten web. The stronger

and stretchier your gluten is, the better. A strong gluten web will be able to support a wet and heavy dough as it rises. If the web is stretchy, it will be able to rise high as the air inside the dough expands in the heat of the oven.

First rise.

After you knead your dough, you will put it in a bowl or a clear plastic container (the better to judge how high it is rising), cover the container with plastic wrap or a damp kitchen towel, and let it stand until it has increased in size. Also called fermentation, this resting period is hardly one of inactivity. Yeast and bacteria in the dough hungrily feed off of the sugars in the flour, creating carbon dioxide, alcohol, and acids. The carbon dioxide, a byproduct of yeast as it feeds, is trapped in the gluten web, causing the dough to rise. You’ll be able to smell the alcohol, also a byproduct of yeast (the same reaction turns grape juice into wine) as the dough ferments, but it will cook off during baking. Bread-friendly bacteria called lactobacilli are also fermenting, consuming sugars that the yeast can’t digest. The byproduct is acid, which gives dough its slightly tangy taste.

Punching down.

I don’t love this term, because in its suggestion of violent deflation of the dough it is misleading. After the dough has fermented for a while, it has built up quite a bit of carbon dioxide. Too much carbon dioxide will begin to kill off the yeast, so it’s necessary to release some of that carbon dioxide by pressing on the dough. Don’t punch it! Just gently sink your fist into its center to partially deflate it. Breads that are distinguished by a large, open crumb structure (ciabatta, focaccia, pizza) should be handled even more gently. Lifting the dough out of the bowl by sliding both hands under it, letting it fold itself over your hands, and then placing the folded dough back in the bowl will expel enough gas from these doughs to safeguard the yeast while preserving the air pockets.

Dividing and shaping.

When your recipe makes two or more loaves, you must divide the dough after punching it down or turning it. Do this gently, using a bench scraper or sharp chef’s knife to cut cleanly through the dough and without destroying too many air pockets. You may be instructed to let the dough rest for 5 or 10 minutes after you’ve divided it before proceeding with shaping. This is to allow the gluten to relax, so the dough won’t be so bouncy and difficult to roll or stretch into a round or a baguette.

Shaping is important not just because it determines the final look of the loaf, but because it provides one last opportunity to stretch the gluten and give the bread structure. In addition, shaping creates surface tension, tightening a “skin” around the loaf, which helps it keep its shape as it rises a second time.

Proofing.

When you’ve shaped your loaves, loosely cover them with a floured kitchen towel or sprinkle some flour over them and loosely cover with plastic. Then let them stand, giving them time to ferment further. Proofing allows more time for the dough to develop a good, yeasty flavor as the yeast continues to feed on the sugars in the flour. Proofing also allows the loaves to increase in size.

Baking.

This is perhaps the most dramatic of all of the stages. When cool dough comes in contact with a preheated baking stone in a very hot oven, several reactions occur: Gases expand, alcohol boils, yeast becomes briefly but significantly more active, and as a result of these three reactions a lot of steam is produced. If you peek through the oven window, you can almost see the loaves growing before your eyes, a phenomenon known as “oven spring.”

After 15 or 20 minutes, the breads will have expanded fully. As the interior of the bread reaches 140°F (60°C), the starches begin to gelatinize and the proteins coagulate, making the bread firm and solid. At about 200°F (95°C), the moisture that has been attached to the starch molecules will begin to migrate toward the crust, a process called starch retrogradation. Even though the crust may look well browned, it is important to keep baking the bread until the crust is firm, a sign that starch retrogradation is almost complete. If you pull the bread out of the oven before this, water molecules will be trapped in the crust, making it soft and soggy rather than crackly and crisp.

Cooling.

Cut into your just-baked loaf and it will still feel damp and doughy inside. But let it cool for a while to allow the process of starch retrogradation to continue, and the inside of the bread will firm up as the crust crisps.

Q

What happens to dough when fat, like butter or olive oil, is added?

A

There are many examples of bread dough enriched with fat: Parker House rolls, brioche, challah. Fat lends tenderness and flavor to the breads. But fats also react on a molecular level with the other ingredients in the dough. If added at the beginning of mixing, fat will coat the proteins in bread, preventing them from bonding with each other and forming a gluten web. This reaction is desirable in some baked goods — tender pie pastry depends upon fat’s gluten-blocking ability — but if you want your enriched bread to rise high it is better to knead it for a few minutes first, to develop the gluten, before adding the fat.

Q

My recipe gives measurements for flour and other ingredients by volume and weight. Is one set of measurements better than the other?

A

Every professional baker and every serious amateur will weigh ingredients rather than measure them by volume. It is the only way to ensure uniform-quality breads, time after time. Depending on how you measure it and how much it has settled since being bagged, a cup of flour may weigh anywhere from 5 to 5½ ounces. If a typical bread recipe calls for 4 cups of flour, and sometimes you use 16 ounces while other times you use 18 ounces, your dough will feel different and your bread will bake differently every time. Of course,

flours vary in absorbency from brand to brand and from season to season, and even if you measure your flour to the last ounce every time you will sometimes have to adjust a recipe, adding a little more flour or a little more water, depending on the flour, the humidity, and other variables. But don’t let weight be one of them. For tips on buying a kitchen scale for baking, see

page 56

.

If you don’t have a scale, go ahead and measure your ingredients by volume. Use the “dip and sweep” method for measuring dry ingredients, dipping your measuring cup into the flour and then leveling off the cup with a knife. Take extra care when measuring by volume to pay attention to how your dough looks and feels as you knead it, making adjustments as necessary.

Q

Is it okay to use tap water to make bread, or is bottled water better?

A

If you are cultivating a sourdough starter, it’s best to begin with bottled spring water, which doesn’t have a high level of chlorine or minerals that may inhibit the growth of yeast. But when it comes to baking bread itself, whether you are using a well-established sourdough starter or packaged yeast, chlorine and minerals won’t affect the bread’s rise. You may want to substitute bottled water for reasons of taste, however. Use the same water in your bread that you regularly drink. If you don’t regularly drink your tap water because it tastes terrible, chances are it will impart its off flavor to your bread.