The Battle for Gotham (12 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

As I kept writing about preservation, I observed the full spectrum of local issues and incremental change of which preservation was just one part and recognized it as a precursor of genuine positive change, the kind that fertilizes and enriches, not undermines and erodes. In many communities, people weren’t just fighting to preserve old buildings. They recognized that the threatened buildings and the varied uses contained in them were important threads in the urban fabric. And they weren’t just fighting to save them. They were buying some of them, fixing them up, opening new businesses, committing themselves to their community—all precursors of more good things to come, to be sure.

Of course, many demolition projects were opposed for reasons other than preservation. But, Jane Jacobs observed, “if you listen closely to people at public hearings, you will understand their fears.” Most opponents of a demolition and replacement plan were resisting the particular manifestation of change, not change itself; erosion, not progress, as Jacobs articulated. I found their stories compelling.

Urban planning professor Robert Fishman notes, “The city was caught up in this riptide of destruction that seemed to have no end” that combined with “a rolling wave of abandonment and sprawl in the terrible period of the ’70s and ’80s,” challenging some to wonder if cities were viable.

1

So, to me, the great value and real meaning of historic preservation were not just about preserving neighborhoods but about preserving urbanism and the city itself.

New York was not alone. Increasing numbers of civic resisters fought both highway and urban renewal projects across the country. With the 1956 Federal Highway Act, many places were gaining a reputation among citizens for decision making by bulldozer that left a legacy of urban blight and empty cleared land still evident today. Preservationists not only valued what was being lost but recoiled in horror at the ribbons of concrete and barracks of brick that emerged to replace long-established places and communities.

Historic preservation is an indicator of urban change. This is true in all cities. In retrospect, I think it is one of the things that gave me reason for optimism in the 1970s. The resilience of the city and its people was clear in these battles. The city was bleak and, to some, seemingly hopeless. But as I watched the positive personal and communal energy expended on behalf of places around the city, it was clear something creatively new was under way.

THE TIDE TURNED

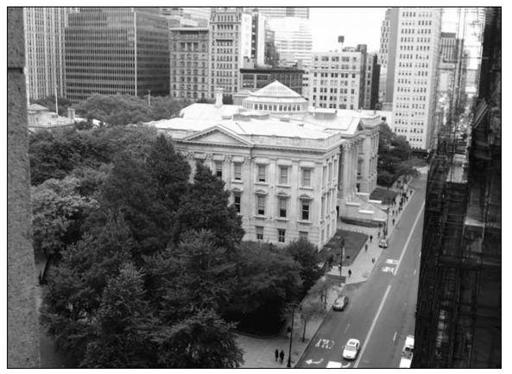

Early in the new administration of Mayor Michael Bloomberg, a controversy arose over the use of one of the city’s premier landmarks, the Tweed Courthouse, an imposing neoclassical building located directly behind City Hall. This was early in 2003 and in itself was an incredible sea change from the mid-1970s when the administration of Mayor Abraham Beame planned to demolish and replace that legendary 1871 building.

2.1 The Tweed Courthouse today. It was almost torn down in the 1970s.

Jared Knowles

.

Who should get to use this monumental landmark became a high-level, much publicized fight. What a novelty! What a milestone! How far the very concept of historic preservation had come in New York; the fight was now over

how to use

a landmark, not

whether to lose

a landmark.

Nowhere was this extraordinary turnaround noticed—at least publicly during the 2003 controversy. New York had forgotten its recent history. Looking at New York through the prism of changes in historic preservation—its victories, its losses, its laws, public policies, and public attitudes—spotlights some of the differences between the city of the 1970s and now.

Today, the restoration and continued use of such notable buildings as Tweed Courthouse—especially publicly owned ones—are almost taken for granted. This marks a total reversal of conventional thought and public policy of a mere thirty years ago. And while a significant number of real estate developers profiting from the conversion of landmark buildings now extol the virtue of the historic preservation they disdained not that long ago, their appreciation is limited by how much they experience interference with their own development plans.

People no longer assume an old building has outlived its usefulness. New is no longer assumed to be automatically better and more economically viable. That was the convention in the 1960s and ’70s. And while today developers with the right political connections can still keep landmark status off their property, they can’t change either the preservation experts’ or the public’s judgment of a building’s worthiness for designation. As people witness the need for total renovation of relatively young buildings dating from the 1960s and ’70s, they recognize even more the inherent value of the solidly built old. So many buildings built in the 1960s and ’70s require more drastic upgrades than buildings twice their age.

A request for approval for demolition of a designated landmark from the Landmarks Preservation Commission is almost unheard of today. How actual landmarks are handled can be a different issue. In fact, now many developers instead request the official landmark designation they need to qualify for lucrative federal preservation tax credits. The weekly calendar of the commission is filled with applications to restore and upgrade landmark buildings of all kinds in every corner of the city. Many developers seek the zoning breaks available with the restoration of a designated landmark. Restoring a landmark is now a prestigious endeavor. For developers, preservation now pays. The record is clear: no designated landmark has shown to be an economic failure

because

of its designation; in fact, most are a financial success.

PRESERVATION ACCELERATES CHANGE

To appreciate where preservation in New York and, in fact, the country, is today, one must understand the progression of the past thirty years. New York set the standard for the country. The rescue, and reuse, of Tweed Courthouse is, in fact, a small measure of how much things have changed from the New York City of the 1970s. Considerable mythology has grown up around the background to passage of the law and the history of landmarks preservation in New York.

Few remember—if they ever knew—that the 1965 Landmarks Preservation Law was almost meaningless in its first iteration. The law’s administration was unimpressive for several years after passage, but it lulled the public into assuming significant progress was occurring. Some obvious buildings were being designated landmarks, but important buildings were falling all over town to make way for the postwar definition of progress that only meant new. Amazingly, under the new law, the Landmarks Preservation Commission was allowed to designate for only six months every three years. It is important to fully understand what that meant—six months of designations followed by three years of unstoppable demolition. This became clear to me only, as this chapter will show, while covering what appeared to be a routine protest over a building demolition in the early 1970s.

The actual reasons for passage of the Landmarks Preservation Law in 1965 are misunderstood. It had more to do with Robert Moses than is at all recognized. The common assumption is that it was prompted by the highly publicized loss of Pennsylvania Station in 1963 and was meant to prevent future disastrous losses. This was definitely not the case. In fact, the demolition of Penn Station—universally recognized today as a monumental act of civic destruction—was at the time greeted with limited and polite opposition. The small group of citizens, preservationists, architects, journalists, and historians who picketed in front of the station did not inspire broad protests. Even an eloquent

New York Times

editorial written by Ada Louise Huxtable—“we will be judged not by the buildings we build but by those that we destroy”—had little impact.

When it was all over, when the last of the incomparable Corinthian columns was carted off to a New Jersey landfill, the full measure of the loss began to sink in. Perhaps the questioning of what is meant by “progress” was accelerated but nothing more dramatic than that. If it was true that the landmark law was a reaction to that loss, the administration of Mayor Robert F. Wagner would have seen passed a very different law, a law with teeth. Instead, the 1965 law can be said to have produced a set of baby teeth; a mature set of teeth came almost ten years later.

The further assumption that New York’s law immeasurably changed the nature of planning and architecture in the city and the whole country, as many suggest, did not really happen for many years. What actually changed everything was the 1978 U.S. Supreme Court decision that upheld the city’s 1965 landmark law in the Grand Central Terminal case. Even the city’s fight to save the law might not have happened if city and commission leaders followed their first inclination to give into Penn Central Corporation and remove landmark status from that stellar gateway to the city. Public pressure made them defend it.

New York was early but not first in the preservation game. In the 1930s, due to the advocacy of vigorous women’s groups, New Orleans and Charleston, South Carolina, were the first nationwide in preserving historic structures and districts of styles that set them apart from most of the country, especially big cities like New York. Determination to preserve these cities’ unique architecture was strong, and protectionist laws were established. In fact, women in Junior Leagues, garden clubs, and similar women’s organizations in several other American cities were the real vanguard of the historic preservation movement nationally. From Providence, Rhode Island, to San Antonio, Texas, women led the fights to preserve their cities.

A PROBLEM GROWS IN BROOKLYN

Weak as it was, this first iteration of the law in 1965 for New York City, perhaps late in the game, was an important turning point, psychologically for the public at least. Most important, it addressed a number of prickly political problems faced by Mayor Wagner in the first half of the 1960s. Urban renewal, highway clearance, and a whole host of Robert Moses excesses had stirred up serious public discontent. The battles were fresh in the public’s mind. Mayor Wagner needed something to pacify a disgruntled citizenry.

In Brooklyn Heights, a new civic battle was brewing over an urban renewal clearance project adjacent to what was to become the historic district. This activist neighborhood already had a track record of taming Robert Moses. In the 1950s, he wanted to plow the Brooklyn Queens Expressway through the neighborhood. The well-fought battle was resolved brilliantly with the expressway going under the Brooklyn Heights Esplanade that overlooks the New York Harbor.

In Greenwich Village, several fights (to be explored in the next chapter) had given Mayor Wagner a black eye: the plan to drive a road through Washington Square Park (1955-1956), the attempt to demolish most of the far West Village for urban renewal (1961), and the fight against the Lower Manhattan Expressway (mid-1960s)—all projects pushed by Moses and opposed by Jane Jacobs and others in the movement she gave voice to. Jacobs accused Wagner of still operating under Moses’s rules, even though in 1961 he promised the Village that no “improvements” would happen that were not in keeping with “physically and aesthetically West Village traditions.” And when he said “the bulldozer approach is out,” Jacobs dismissed the promise as “pious platitudes.”

So it is no coincidence that those two historic areas of the city—Brooklyn Heights and Greenwich Village—were the first to be designated historic districts, a move that mollified at least some of the participants in the emerging grassroots community and historic preservation movements.

Other development battles also plagued the mayor. In 1957 Carnegie Hall was scheduled to be demolished and replaced with a forty-four-story vermilion and gold skyscraper surrounded by a sunken plaza lined with cultural exhibits. An elegant rust-colored brick building, Carnegie Hall is internationally famous more for its acoustics than its Renaissance Revival design of 1891, appealing as that may be. But it is clearly architecturally distinctive as well.

Lincoln Center was meant to

replace

Carnegie Hall and the Metropolitan Opera. The city opera and ballet companies were to share a new home at Lincoln Center, moving them out of City Center on Fifty-fifth Street. A very well-publicized protest against Carnegie’s impending loss ensued, led by violinist Isaac Stern, his wife, Vera, philanthropist Jacques Kaplan, and Ray Rubinow, the administrator of Kaplan’s foundation. The public hue and cry was deafening and incessant. But only the combination of the fame and determination of Stern et al., backed by a strong public sentiment, could overcome the formidable combined power of Robert Moses, John D. Rockefeller III (chair of the effort to build Lincoln Center), and Mayor Wagner.

In 2003, Carnegie Hall went through a well-publicized, high-quality refurbishment under the guidance of Richard Olcott of the James Polshek Partnership. Polshek had been the architect for renovations and additions since its rescue in the 1960s. Inexplicably, an exhibit at Carnegie Hall about its rescue and restoration paid little attention to this earliest rescue. I subsequently taped an oral history of both Isaac and Vera Stern to record the story for posterity. Unfortunately, Kaplan was already deceased.

2