The Battle for Gotham (53 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

In his push to make Atlantic Yards a reality, Bruce Ratner has crafted the most sophisticated political campaign the city has seen in a very long time, better than any professional politician has mounted to win elective office, complete with gag orders and aggressive polling. And even if Atlantic Yards was wildly disproportionate to the surrounding neighborhoods, its pillars seemed laudable (the subsidized housing) and potentially cool (Gehry; having the NBA’s Nets nearby). The developer, Ratner, seemed downright enlightened: a commissioner of consumer affairs under Ed Koch who’d gone out of his way to hire women and minorities to build his other projects.

21

Smith might also have noted the deceptiveness of the affordable-housing promise. Not only has the promised number of units shrunk since first announced, as predicted, but the money to construct them would be coming from normal public funding sources, not from Ratner’s development coffers. In other words, those units could be built now, elsewhere, without Atlantic Yard’s construction. If Ratner really cared about creating affordable housing, he could do it now elsewhere in the city. And if such housing is constructed in the future and those public funds still exist, money used here will not be available for similar housing elsewhere in the city. That funding source is finite. And since any affordable units built here will be more expensive to construct than elsewhere, a disproportionate share of the citywide resource will get used here.

So, since its announcement in December 2003, where does the project stand? In light of the current economic crisis, this is hard to say. Ratner tried and failed to get a bailout from the stimulus package to build the

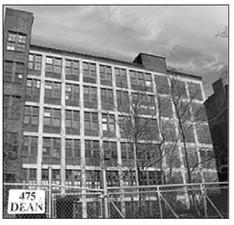

10.3 Dean Street loft co-ops on the Atlantic Yards site, formerly fully occupied. The building has been empty since 2005 and is scheduled for demolition.

Tracy Collins

.

arena. Mayor Bloomberg has denied any increase in city funds. Court challenges continue. In September 2009, Russian billionaire Mikhail Prokhorov agreed to buy 80 percent of the money-losing basketball team and to invest in the larger project. The details remain unclear. One cannot predict what will finally emerge from this overblown proposal. Cynics could easily observe that building the arena for his own team, the Nets, was Ratner’s goal to begin with, the rest being window dressing. If anyone really thought that the Gehry-designed development had a chance of evolving as presented for state and public approval, well, then, I have a bridge to sell them.

Ratner would have undoubtedly sold off parcels to other developers to design as they saw fit within the zoning. He still can. Wrote

New York Times

critic Nicolai Ouroussoff, who had high praise for Gehry’s design: “New York has had a terrible track record with large-scale planning in recent years. Look at Battery Park City. The MetroTech Center.

22

Donald Trump’s Riverside South. All are blots on the urban environment, as blandly homogeneous in their own way as the Modernist superblocks they were intended to improve on.”

23

Ouroussoff points to Rockefeller Center as a prime and glorious example of what this city was once capable of producing. Yet Rockefeller Center evolved. It started as a planned site for an opera house, changed with the times, was designed by thirteen different architects, connected seamlessly to the existing grid (even adding a street), is totally geared to pedestrians and mass transit, not cars, and did not overwhelm the airspace of its site.

The alternative to Ratner’s proposal had smaller and more manageable components and relied on more than one developer. This could have produced some notable new buildings. The most critically acclaimed buildings designed and built around the city in recent years are on single infill sites, mostly in historic neighborhoods. The scale of the alternative would be more compatible with the existing urban fabric, even including reasonably tall buildings. The surrounding neighborhoods thus would not be overwhelmed. Viable buildings would not be lost nor current residents and businesses displaced. Development and new growth could have continued as they had in the prior decade, step by step, in modest doses. Transportation and pedestrian connections to its surroundings and to the downtown core would be more reasonable. All of this would add up to the kind of development in small or modest doses that leads to big but appropriate change. The alternative design would have had a better chance of genuine public approval and of getting off the ground. What a missed opportunity.

In fact, one of two Dean Street resident architects who offered alternative plans suggested razing the Atlantic Center mall, a much maligned suburban-style enclosed shopping complex built in the 1990s by Ratner just north of the arena site. (A few government agencies occupy space here. This is a typical way government helps economically challenged developer projects.) “If Mr. Ratner were willing to condemn his own property, he would be able to build his arena without displacing anyone from their homes,” architect Karla Rothstein, a Dean Street resident who worked on an alternative development, told

Times

reporter Bagli. “It would be an improvement on the existing mall,” she added.

Another important consequence of the alternative should be noted. The city would not lose the taxes, residences, businesses, and jobs of the site for the decades that most of this land will lie fallow, just like so many earlier Robert Moses clearance projects did. The losses on these sites is never calculated, just the promises of the new taxes and jobs to come eventually. Those jobs may not even materialize as promised. Seldom does the city or anyone go back after a project is finished to see if promises have been met. And in how many projects have we seen fewer jobs created than promised and then seen those jobs disappear within a short time after completion? The tax incentives that came with those promises are rarely removed.

Measuring the taxes and jobs is fundamentally the wrong way to evaluate a plan, in any case. One must consider how it affects a wide area, including the whole city, and not just the site. Otherwise, everything will continually be suitable for replacement, no matter how well the site still functions. “Just replacing a dime store with a larger five and ten doesn’t benefit the city in the long run,” notes Ron Shiffman. “Rather, the point is to enable those facilities, like the dime store, to improve themselves. One is a replacement strategy; the other is how an economy grows by nurturing from within.”

What Would Jane Jacobs Say?

Jacobs’s name was reportedly invoked in the early presentations of the Atlantic Yards proposal. Apparently, the Jacobs qualities included a web of streets and sidewalks, although winding suburban style and not connected to the city’s existing grid; ground-floor retail for some of the towers, something every developer now does because it is good business but is also used to claim a Jacobs imprimatur; and, of course, mixed use, which, as shown earlier in this book, is not the Jacobs definition of mixed use but contrasts with Moses’s separation of uses. Since her name was involved, it is appropriate to examine the project against her writing.

First, let’s dispose of the idea that Jacobs was against change or against big buildings or, indeed, a sentimentalist. First, go back to her letter to Mayor Bloomberg about Greenpoint-Williamsburg. That is a ringing endorsement for change, just a different kind of change than what the city was proposing. In addition, one can look at her enthusiastic championing of the planning and zoning changes in the old garment center of Toronto known as the King-Spadina area. Toronto city officials consulted with her and followed many of her suggestions there, today considered that city’s SoHo equivalent. New innovative uses occupy both old and new buildings. New buildings coexist comfortably with old. Once empty or underused old buildings are now full. This is change in a big way. That Toronto district was in no better shape than our city’s so-called derelict old neighborhoods.

And, of course, a true reading of Jacobs’s books versus a pseudounderstanding would indicate her disapproval of everything about Atlantic Yards but also her expectation for continued change and growth, just not Ratner’s idea of change and growth, any more than a Moses plan. A basic Jacobs precept is complexity: no complexity is possible in a monolithic development of this scale by one developer and designed by one architect.

Another basic Jacobs precept is opposition to “cataclysmic” money and development. Surely, this project qualifies as cataclysmic change. The proposal is so inimical to the character of the district and, in fact, the whole borough of Brooklyn that it is off any chart of Jacobs’s principles.

Trying to show how Atlantic Yards contradicts every Jacobs principle can be tiresome. And, in fact, she was too unpredictable for such an exercise. Furthermore, Jacobs was never about how to

develop

or

design

as much as how to

think

about development, how to

observe

and

understand

what works, how to

respect

what exists, how to

scrutinize

plans skeptically, how to

nurture

innovation, new growth, and resilience. That says it all.

As it happens, I had a brief conversation with Jane about Atlantic Yards in one of my last visits with her before her death. The development had only recently been proposed, and she agreed that it was right out of the pages of old, discarded development models derivative of Moses. There was not much to discuss. She shook her head and said, “What a shame.”

On to Columbia University

Atlantic Yards may be the poster child for current Moses-style development in New York, but it is not alone. Columbia University on the Upper West Side gained city approval for a second campus north of its historic 110th Street site that would provide 6.8 million square feet in eighteen new academic and research buildings on seventeen acres in West Harlem and an underground network six stories deep for tunnels, two power plants, parking, garbage collection, and loading docks. The site encompasses more than eight blocks north of 125th Street between the phenomenal architectural structures of two elevated trestles for Riverside Drive and the Broadway IRT subway. Though lacking in gates or fences, this second campus will feel separated and segregated from the neighboring city. Under single ownership and patrolled by a private security force, this academic island will undoubtedly feel isolated, even if connected to the actual grid and planned skillfully by an accomplished city planning team under the leadership of Marilyn Taylor of Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill.

Like Atlantic Yards, Columbia targeted a semi-industrial, seemingly derelict neighborhood that to the contrary combined regenerative precursors interspersed with opportunities for infill development of varying scale. And like Atlantic Yards, both Columbia’s purchase and emptying of properties along with the threat of eminent domain blighted the area, although new businesses, especially restaurants, kept opening in the neighborhood, despite their location under and within sound impact of both viaducts. In fact, enough new restaurants have opened in reclaimed warehouses along Twelfth Avenue to be dubbed “restaurant row” and “a culinary hot spot” for West Harlem.

Unlike Atlantic Yards, however, Columbia could have achieved 85 percent, if not all, the expansion that it says it needs (predicting future needs is always a guessing game) in the next thirty years without erasing a Harlem neighborhood, once known as Manhattanville. That expansion, however, just would not have happened in the same form, with the same design, and according to the same plan as Columbia insisted on.

Forest City Ratner, a private-sector entity with the purpose of making money, is best known in Brooklyn for its two large suburban-style projects, the Metro Tech office park and the Atlantic Center Mall. That is Ratner’s style of development, not an urban vision reflecting a real understanding of how a city—its neighborhoods, economy, and public spaces—really works. But from Columbia University, one of the most prestigious in the country, something different was to be expected. Columbia should not behave like a private developer with a suburban view of the city. This 254-year old institution is home to a highly respected planning program, the first historic preservation program at any university in the country, and an impressive roster of urban experts, such as Mindy Fullilove, mentioned earlier, a professor of clinical psychiatry and public health who has written so extensively about the impacts of the ruptured social bonds in communities decimated by urban renewal.

So when Columbia unveiled its proposed new academic enclave necessitating the total clearance of a neighborhood, Moses style, urbanists were correct to be stunned. The individual glass-covered, almost transparent buildings were designed by the world-renowned architect Renzio Piano. The pattern of enlisting “starchitects” merely for the purpose of advancing otherwise troublesome plans had become familiar in recent decades. Both Atlantic Yards and the Columbia plan are perfect examples of this trend.