The Battle for Gotham (6 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

1

THE WAY THINGS WERE

I

am a creature of the city I was born in. Although my parents contributed, it was the city—with its vibrancy, diversity, challenges, and choices, along with its sights, smells, and sounds—that raised me and shaped my urban sensibility. Our move to a Connecticut suburb shaped me also. It gave me a taste of another way of life, one that sharpened my urban sensibility. Mine is a New York tale, but more than that, my family story parallels that of millions of Americans and illustrates patterns of social change that altered the face of American cities, not just New York.

My parents were both the children of immigrants, both born and raised in Brooklyn, enthralled by the American dream as defined in the early decades of the last century. I was the first of my family to be born in Manhattan, a tremendous achievement for my parents’ generation, as moving from Brooklyn to Manhattan was a mark of accomplishment.

My father was in the dry-cleaning business, first learning the business by working for someone else, then opening his own store with money borrowed from the family circle, and expanding that business into a small chain of four stores in Greenwich Village.

1

This pattern of entrepreneurial evolution was typical of new immigrants and their children. It still is. One can observe this happening, particularly in immigrant neighborhoods, in cities everywhere. Borrowing from the “family circle” or “community network” has always been the first step in new immigrant business formations. My family was no exception. Conventional banks are an intimidating, alien experience and not usually welcoming to immigrants.

The main store was on Eighth Street between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, then the primary shopping street of Greenwich Village. The plant, where garments from all four stores were cleaned, was on West Third Street, around the corner from where we lived. When I was very young, my mother worked there with my father while my older sister and I were in school. My mother enrolled in a decorating course at NYU (neither of my parents had been to college) and eventually became a professional interior decorator (today she would be called an “interior designer”). She developed an active career gaining clients through word of mouth.

We lived in a spacious apartment on the sixth floor of a twelve-story building on the south side of Washington Square Park with windows overlooking the park. My mother could keep an eye on me when I played in the park or beckon me if I overstayed my playtime. Roller skating, jumping rope, swinging a leg over a bouncing Spaldeen to the “A My Name Is Alice” game, and trading-card games against walls of buildings were favorite pastimes.

2

Others played stoopball, stickball, curb ball, and many more. The variety of kids’ games on the sidewalks and streets of the city is infinite. The vitality that this street activity represented, under the watchful eyes of parents and neighbors, was often misinterpreted as slum conditions.

Television was not yet affordable for my family, but I had a friend on the twelfth floor who enjoyed that luxury. Every Tuesday night, I would visit her to watch Uncle Miltie (Milton Berle). Occasionally, I also got to watch Sid Caesar’s

Show of Shows

or, just as exciting, Ed Sullivan. I even saw the show on which he introduced the Beatles.

I walked seven or eight blocks to school; played freely and endlessly in the park; listened to folk singers who gathered regularly at the Circle (the local name for the big circular fountain); traveled uptown to museums, theaters, and modern dance lessons; and shopped Fourteenth Street for inexpensive everyday clothes and Fifth Avenue uptown for the occasional more expensive special purchases.

On Christmas Eve, my parents, my sister, and I would take the Fifth Avenue bus up to Fifty-ninth Street (Fifth Avenue was two-way then) and stroll down to Thirty-fourth Street to enjoy the exuberant Christmas windows of the department stores. While all the department stores competed to produce the most artful window displays, Lord & Taylor always won hands down; Saks Fifth Avenue and B. Altman alternated for second place. Even the few banks and airline offices then on Fifth Avenue put on a good display. Then we would take the bus the rest of the way downtown and join carolers singing at the huge Christmas tree under the Washington Square Arch. It was a great tradition. The city was a delightful place to be in the 1940s and 1950s.

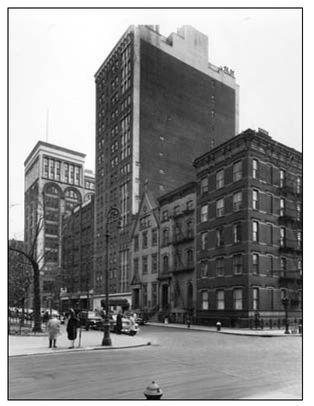

1.1 My apartment house and block on Washington Square South before condemnation.

NYU Archives

.

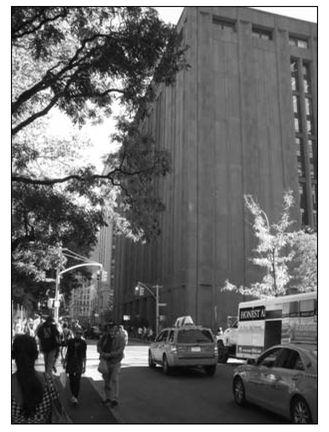

1.1a NYU’s Bobst Library replaced my block.

Jared Knowles

.

THE PUSH-PULL EFFECT

Two things led my family to move to Westport, Connecticut, then a paradigm of suburbia. Opportunity beckoned my father. The first strip shopping center, with the area’s first branch of a New York City department store, had opened in Westport. Like in so many downtowns across America, this one was a short distance from downtown, enough to draw business away. Across from that, only minutes from Main Street, a second was about to open. The builder of the second center wanted to include a dry-cleaning store. He wanted my father to be the one to do it.

Strip centers across America of that time imitated city shopping streets and actually repackaged in a planned version the successful commercial mix that evolved spontaneously on urban streets. Developers went by a formula that included a mixture of service and specialty stores. Thus, the builder wanted a dry cleaner to locate between the supermarket and the baby-clothes store, with the hardware, carpeting, and other stores and the luncheonette to follow down the line. The offer was a hard-to-resist business opportunity for my father.

My father hungered for the appeal of suburban life, but my mother definitely did not and never settled into it happily. “You pay a stiff price for that blade of grass,” she used to say. Nevertheless, opportunity was having an irresistible pulling effect on my father. We made the switch.

My mother resisted the stay-at-home suburban-housewife lifestyle, but she definitely got caught up in the car culture. My father drove a secondhand Chevy station wagon, but my mother’s first car was a red Ford convertible with a V8 engine and stick shift. If she had to be in the suburbs, she wanted a fun car. A few years later, her second car was similar but in white. Both cars were guaranteed boy magnets in the parking lot on the very rare occasion that I was permitted to drive her car to school. For after-school activities, most of the time, I hitchhiked or biked to my destination. My mother refused to be a chauffeur.

While opportunity and suburban living were having a pulling effect on my parents, three negative forces intruded on our balanced urban existence and helped push us over the edge. The Third Street building in which my father’s main “plant” (I never knew why it was called a plant) was located was condemned as part of a large urban renewal project, devised by Robert Moses. “Urban Renewal” was the federal program that funded the major overhaul of most American cities starting in the 1950s. The plant’s Third Street block was part of the sizable chunk of the South Village’s multifunctional, economically viable urban fabric that was sacrificed for subsidized middle-income apartment houses set in green plazas, namely, Washington Square Village and south of that the Silver Towers designed by I. M. Pei. This area, just north of Houston and the future SoHo, had a similar mix of cast-iron commercial buildings, tenements, small apartment houses, and a few federal houses.

Through urban renewal, New York University, not yet the dominant force in the neighborhood that it has become, acquired our apartment building and let it be known that all tenants eventually would have to move to make way for university expansion. Urban renewal, then as now, helped educational institutions expand campuses through eminent domain, the taking of private property for a loosely defined public purpose. Bobst Library, a hulking sandstone library designed by Philip Johnson, was built on the site.

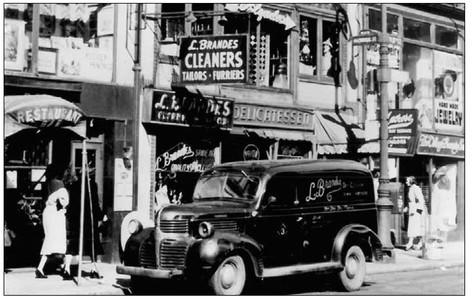

As if losing our apartment and my father’s plant were not enough, underworld forces were muscling in on small businesses, like my father’s on Eighth Street, making it increasingly difficult for business owners like my father to remain independent. The primary site for Larry Brandes Dry Cleaners was centrally located on Eighth Street, at MacDougal. Eighth Street is the Village’s equivalent to a Main Street.

1.2 “L. Brandes Cleaners” was my father’s store on Eighth Street, circa 1930s or 1940s, with delivery truck parked in front.

Eighth Street BID.

PUSHED TO LEAVE

The combination of Robert Moses Urban Renewal and the underworld shakedowns made our departure inevitable. So we moved to Weston, Connecticut, the neighboring town to Westport. My father, having sold what he could of the business in the city, opened in neighboring Westport one of the first cash-and-carry dry-cleaning stores in a Connecticut shopping center. My sister, Paula, was working for a New York advertising agency, and she created a newspaper campaign that started weeks before the opening, playing on the theme of “city to suburb.”

No pick-up and home delivery service was offered in the new store, as had been done in the city, but same-day service and on-site shirt laundering were possible that hadn’t been in his city stores. The store opened in 1953, and I eagerly worked there after school and Saturdays, starting by assembling hangers and eventually waiting on customers.

“Hand-finishing” (a fancy term for ironing) was a service not usually available in dry-cleaning stores. My father introduced that service in Westport. Katie, a woman who worked in the West Third Street plant, commuted from Harlem to Westport to continue working for my father. He picked her up every morning at the train station. Amazingly as well, two of the pressers, Al and Phil, who lived in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant and also had worked on West Third Street, commuted from the city every day to continue working for my father. They were ardent Brooklyn Dodger fans; my father and I were equally ardent Yankee fans. During games—especially pennants and World Series—the store was wild with cheers and jeers. Customers came second.

I remember being fascinated at how many customers knew my father from the Village. “Are you the same Larry Brandes, dry cleaner, that used to be on Eighth Street?” they would ask. They were former city customers, now new suburbanites seeking the same greener pastures as my father. Greenwich Village residents were moving to Westport. The exodus to the suburbs was gaining momentum. We were witness to and participants in a phenomenon that would change the face of America.

Weston, where we moved to, was a small-town adjunct to the larger, better-known Westport. I went to junior high in Weston but high school in Westport because Weston did not yet have one. My father’s store was in Westport.

My father dreamed of building a year-round house. We had the land. Our summer cottage—no heat or winter insulation—was on the site. That tiny two-bedroom house was an expression of family creativity. My father built closets, installed windows where only screens had been, and created a small but efficient kitchen. My sister painted Peter Hunt designs on cabinets and closet doors. My mother sewed slipcovers and curtains. I helped “drip” paint the floors with my mother and sister à la Jackson Pollock. That cottage was demolished to make room for a year-round split-level house, the popular housing design of the 1950s.