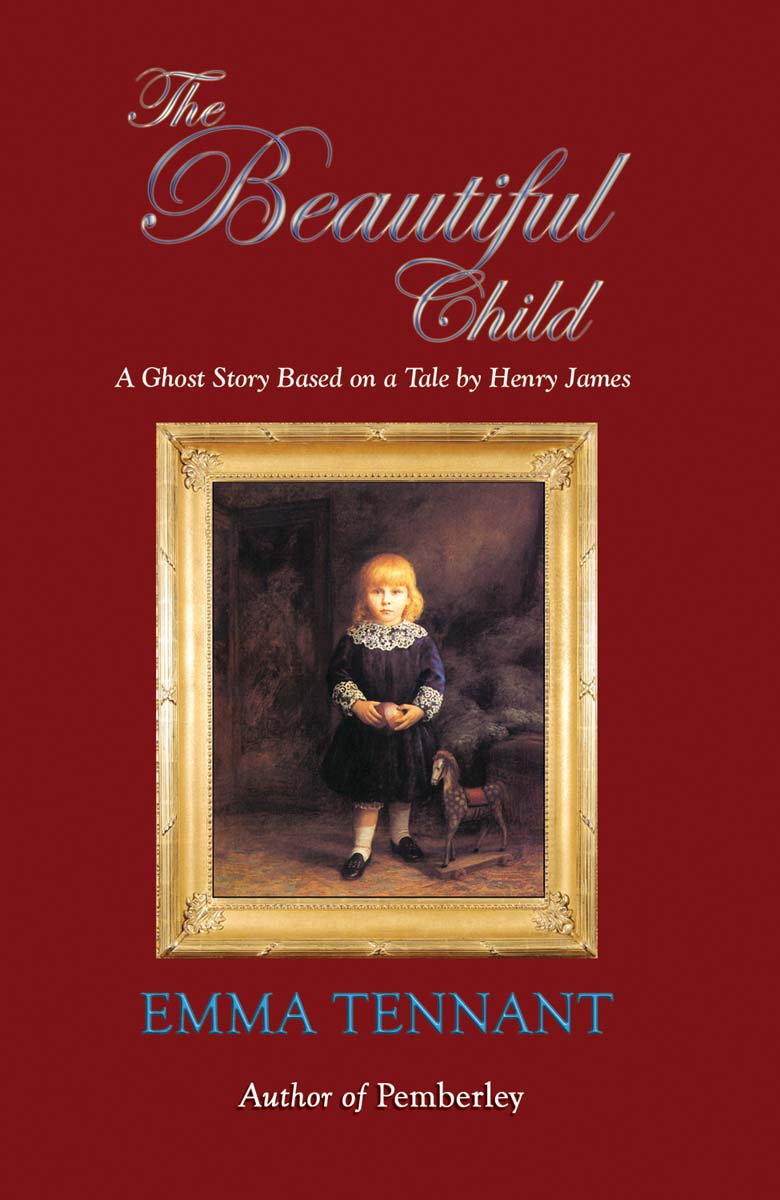

The Beautiful Child

Read The Beautiful Child Online

Authors: Emma Tennant

Lamb House, Rye, East Sussex

Part detective story, part analysis of a writer's urge to place real people within fiction, this is a Christmas fireside tale that examines the horrors of The Turn of the Screw while revealing those of today.

We read Henry James's unfinished tale, The Beautiful Child, with its chilling depiction of cruelty and neglect, which he abandoned in 1902. And we learn about the terrifying scandal behind James's inability to proceed with his story of a couple who beseech a fashionable artist to paint the child they never had â a scandal involving the alcoholic Mr and Mrs Smith who had served James for many years.

Will the chief guest at a house party, an English professor, solve the mystery of the hauntings at James's home, Lamb House, in Rye? This book fills out the unfinished story and ends on a note of terror that would surely have been appreciated by the Master himself.

E

MMA

T

ENNANT

was born in London and spent her childhood summers at the family's Gothic-style mansion in Scotland. Emerging in 1960s swinging London, she worked as a travel writer and features editor for monthly magazines. In 1975 she founded the influential literary magazine Bananas. Her first novel, The Colour of Rain, was published in 1963 under a pseudonym. She became a full-time novelist in 1973 with the apocalyptic The Time of the Crack, later reprinted as The Crack. Many books have followed, including thrillers, comic fantasies, works for children and a series of subversive âsequels' to much-loved classics. Her interest in archetypal narratives has led her to reinterpret other canonical texts in a characteristic voice blending witty fable, social satire, a feminist analysis of patriarchy and an engagement with divided identity. Made Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 1982, she was awarded an honorary D.Litt. from the University of Aberdeen in 1996.

âEmma Tennant has the authentic knack of tapping into one's mental and nervous wiring ⦠to read her is to feel oneself in the grip of something as absorbing and impossible not to respond to as a close family ⦠One of the strengths of her writing is her thrilling dis-junctive oddness. On account of the atmosphere she works up, her fictions are placed in a time that is of our time but not too datingly within it ⦠at once violent and cool.'

â Candia McWilliam

âA difficult writer to pin down, Emma Tennant is one of Scotland's best ⦠Those who have never read her work may be surprised to discover a voice that was recognizably postmodern in the 1960s ⦠If you value the experimental, the surreal, the avant-garde even, or wondered why Scotland never produced an Angela Carter or a J.G. Ballard, Tennant is a writer who will repay your attention ⦠Not fitting in, though, is the essence of her work. What truly good writer wants to “fit in” anyway? She has pursued her intellectual passions, rejecting trends and dodging pigeonholing.'

â Lesley McDowell

To Alan Hollinghurst, with love

PROFESSOR JAN SUNDERLAND

W

e were sitting around the fire at a house not far from Lamb House, where this story takes place â a house, at least, with the same feeling of space and wide skies as the place the Master had loved, the home of his most contrived and ambulatory fictions.

And because it was Christmas, and the talk turned to ghost stories, we all remembered the same one at the same time, the first volunteer my niece Lou, who was fresh studying Henry James at school. We saw â my sister-in-law Mary and the couple who had rented the Edwardian château and Douglas McGill, the friend of my late brother, as well as an assortment of ladies who crowded on to the sofa as if they knew there was something in the air, something intriguing and even wicked perhaps â we all saw the ghosts of the servants as they appeared at Bly in the famous tale. We shuddered, as if a current of cold water swirled briefly around us. We saw Quint and Jessel and the poor corrupted children; and for a while we sat quiet, as if accepting that nothing more awful could ever be written or recounted.

Then one of the women spoke up. âThere were two turns of the screw' was offered, in a casual and almost impatient tone, as it comes back to me. âThe horror of young and innocent children utterly

exposed,

as the governess realized at the time, to unspeakable evil. And the hint that she herself haunted the victims: the terrible turn the torturer provides when it's clear that the protector â the source of safety â is the greatest danger of all.'

âYes â¦' Here my sister-in-law put in her oar, gazing at me for corroboration as she spoke. âBut it's odd that no further turn has come up ⦠I mean â¦'

She became a little heated, I thought, and I wished, not for the first time, that my late brother had been there to reassure her, to allow her confidence once more in what she thought, and I said, âWe live in an age far removed from the early years of the last century.'

Mary nevertheless went bravely on. I saw Douglas McGill look kindly across at his friend's wife â widow, I suppose I must call her â but there was too much death already at that evening of the festive season, and I have no wish to recapture that atmosphere now. âWe are surely aware that our world contains the threat of paedophiles, wherever our children may go â¦' And here Mary broke off, seeing the look on her daughter Lou's face â Lou, still so young, not finished with school, Lou who had lost her adored father just two years before. âThat, I suppose, is what I mean,' poor Mary ended, her worried gaze still on the girl. âThat there are things now out in the open which could never be said at the time of the writing of the tale. Things considered too disgusting and shocking to be printed. You know?' And, with a beseeching glance at Douglas and a blush that appeared to settle on her brow and then move downwards to form a fiery ring about her neck, Mary at last fell silent.

But the last thing I could have expected happened next. Douglas, her late husband's best friend, rose and went over to the upright chair (the ladies, as I shall persevere in calling them, had taken the sofa and two armchairs) where my sister-in-law had modestly placed herself after dinner. âMy dear Mary, I must congratulate you on your candour and bravery. For I must tell you ⦠and here he looked around and included us in his audience: not one of us, I saw, refusing this invitation. âI must tell you,' he repeated and this time let out a sigh along with the words, âthat there is confirmation of what you have told us. A scene of horror impossible to exceed â a tale of perversion and corruption which cannot be paralleled anywhere in the world.'

âBut where did it actually happen?' demanded the young woman who had been first to express disapproval at the non-existence of a modern rival to James's ghost story. âWas it at Bly?'

âNo.' Douglas was smiling now, as if determined to humour the outspoken occupant of the deep sofa.

âAre you going to tell us?' Lou asked, her manner a good deal more composed than her mother's flaming cheeks would suggest. âWas it a house we know about? Are we â¦' And here she laughed as the idea occurred to her. âAre we in that house now?'

No, McGill assured us, and I saw the quick look of relief on the face of the young woman who had been most vociferous in her insistence that modern horrors would intensify the effect of James's tale (following my sister-in-law, I may say â but that was Mary's destiny, never to be recognized for an original thought).

âNo, the action, if that is an accurate description of a ghost story, took place at the author's home. No country house needed to be invented, no staff or visitors were in search of names. Anyone reading or researching the work of Henry James â¦' And here McGill smiled down at my niece, and I saw the pleasure she felt at being included â in a game, a literary quiz, a ghost hunt, whatever it was, she was likely to be the best qualified in our assembled company that night â and I wished for her, as I had wished for her mother earlier, a small triumph, if only to win over the arrogant ladies on the sofa.

âYes, Lamb House,' McGill said quietly when Lou, shy as ever, half whispered the name. âThere, in Rye, where the Master had found the house he had always desired â the house and walled garden and the Green Room where he could dictate his great novels â¦'

âBut how does a further turn of the screw come into this,' demanded the assembled harpies (as I was now regarding them) now settled ever deeper on the sofa and consuming a tray of dark chocolates. âSurely he can't have haunted himself,' the outspoken one continued. âI mean, either you are dead or you are alive and you see dead people. How was it possible â even for Henry James â to be in both states at the same time?'

Now I felt my niece's discomfort at the reference to death and to a haunting uncomfortably close to home, and I looked over at McGill and asked him how this new twist to the famous story had reached him. âUnless you were visited yourself by the Master,' I said, hoping to lighten the mood of the audience; but Lou, I saw, disliked the subject, and everyone fell silent.

âIt is best that I give you the whole story,' McGill said. A sigh of agreement went up, the harpies sat forward to give the teller one more chance, and my sister-in-law Mary even went so far as to say she would sit up all night if necessary to hear the solution of the haunting at Lamb House.

Various voices now rose in expectation. âIt's about an incubus,' suggested Lou demurely â referring, of course, to

Owen Wingrave,

the tale of the boy who, by spending the night in a haunted room, sacrificed his life in order to save his family.

âNo, no,' cried the outspoken harpy, and in her excitement the box of bonbons tumbled from her lap on to the floor. âShe was right the first time â¦' And I saw poor Mary blush again at being singled out. âThe haunting must have been to do with a child. Disgusting, pornographic! I can't wait!'

It took several minutes for the general excitement to wear off, and Douglas appeared harried. Suddenly one couldn't help feeling sorry for the man, unaware as he had clearly been of the appetite of the ladies on the sofa for the unspeakable. Once he could make himself heard, I must add, I thanked him silently for defusing the atmosphere â if that is the best way to describe the abrupt change of mood of the company once McGill's need for a postponement was made clear.

There was a lady, it seemed, who had transcribed the whole story of the horrors at Lamb House â and McGill would ensure her testimony would arrive the next day. A friend, an antiquarian bookseller who had been a friend of the lady (she had died at a great age in the 1960s), was expected in the vicinity, staying with friends over the New Year. He would bring a computer disk, and we could hear the tale to our hearts' content.

âDisk?' queried my erudite niece. âSurely there was no such thing at the time of James's death in 1916? Now how did the story, I wonder, get on disk?'

But McGill was giving away no more. By rising and walking firmly over to his late friend's widow â she took his arm gratefully, I couldn't help noticing, and I saw I was expected to applaud their friendship and possible future marriage I must confess â he had ended the evening.