The Best of Joe Haldeman (11 page)

Read The Best of Joe Haldeman Online

Authors: Joe W. Haldeman,Jonathan Strahan

“Spread out, dammit! There might be a thousand more of them waiting to get us in one place.” We dispersed, grumbling. By unspoken agreement we were all sure that there were no more live Taurans on the face of the planet.

Cortez was walking toward the prisoner while I backed away. Suddenly the four men collapsed in a pile on top of the creature.... Even from my distance I could see the foam spouting from his mouth-hole. His bubble had popped. Suicide.

“Damn!” Cortez was right there. “Get off that bastard.” The four men got off and Cortez used his laser to slice the monster into a dozen quivering chunks. Heartwarming sight.

“That’s all right, though, we’ll find another one—everybody! Back in the arrowhead formation. Combat assault, on the Flower.”

Well, we assaulted the Flower, which had evidently run out of ammunition (it was still belching, but no bubbles), and it was empty. We scurried up ramps and through corridors, fingers at the ready, like kids playing soldier. There was nobody home.

The same lack of response at the antenna installation, the “Salami,” and twenty other major buildings, as well as the forty-four perimeter huts still intact. So we had “captured” dozens of buildings, mostly of incomprehensible purpose, but failed in our main mission, capturing a Tauran for the xenologists to experiment with. Oh well, they could have all the bits and pieces they’d ever want. That was something.

After we’d combed every last square centimeter of the base, a scout-ship came in with the real exploration crew, the scientists. Cortez said, “All right, snap out of it,” and the hypnotic compulsion fell away.

At first it was pretty grim. A lot of the people, like Lucky and Marygay, almost went crazy with the memories of bloody murder multiplied a hundred times. Cortez ordered everybody to take a sed-tab, two for the ones most upset. I took two without being specifically ordered to do so.

Because it was murder, unadorned butchery—once we had the antispacecraft weapon doped out, we hadn’t been in any danger. The Taurans hadn’t seemed to have any conception of person-to-person fighting. We had just herded them up and slaughtered them, the first encounter between mankind and another intelligent species. Maybe it was the second encounter, counting the teddybears. What might have happened if we had sat down and tried to communicate? But they got the same treatment.

I spent a long time after that telling myself over and over that it hadn’t been

me

who so gleefully carved up those frightened, stampeding creatures. Back in the twentieth century, they had established to everybody’s satisfaction that “I was just following orders” was an inadequate excuse for inhuman conduct...but what can you do when the orders come from deep down in that puppet master of the unconscious?

Worst of all was the feeling that perhaps my actions weren’t all that inhuman. Ancestors only a few generations back would have done the same thing, even to their fellow men, without any hypnotic conditioning.

I was disgusted with the human race, disgusted with the army and horrified at the prospect of living with myself for another century or so.... Well, there was always brainwipe.

A ship with a lone Tauran survivor had escaped and had gotten away clean, the bulk of the planet shielding it from

Earth’s Hope

while it dropped into Aleph’s collapsar field. Escaped home, I guessed, wherever that was, to report what twenty men with hand-weapons could do to a hundred fleeing on foot, unarmed.

I suspected that the next time humans met Taurans in ground combat, we would be more evenly matched. And I was right.

~ * ~

INTRODUCTION TO

“ANNIVERSARY PROJECT”

Harry Harrison asked me to do a story for an anthology of science fiction set one million years in the future. I wrote the first three pages of this one and ran into a wall. Started over, stopped again. Tried several angles and kept getting stuck.

Finally I wrote Harry and said I couldn’t make the deadline, and those pages went into the “maybe someday” file.

Several years later, I came across the fragment in the proper mood,

I guess, and immediately saw what was wrong—it was hamstrung by success. I wanted these “people” a million years in the future to have evolved into something totally alien, and in fact they were so alien they didn’t have certain interesting attributes: love, hate, fear, death, birth, sex, appetites, politics. They did have ontological disagreements, but that’s pretty dry stuff.

But in fact

as aliens

they did work pretty well. Most aliens in science fiction, it says here, aren’t truly alien, because the purpose of an alien in a story is to provide some sort of refraction of human nature. But I wasn’t really aiming that high. My aliens were there as unwitting vehicles for absurdist humor. All the story needed was a couple of bewildered humans, to act as foils for

alien

nature. Once I saw that, the story practically wrote itself.

ANNIVERSARY PROJECT

H

is name is Three-phasing and he is bald and wrinkled, slightly over one meter tall, large-eyed, toothless and all bones and skin, sagging pale skin shot through with traceries of delicate blue and red. He is considered very beautiful but most of his beauty is in his hands and is due to his extreme youth. He is over two hundred years old and is learning how to talk. He has become reasonably fluent in sixty-three languages, all dead ones, and has only ten to go.

The book he is reading is a facsimile of an early edition of Goethe’s

Faust.

The nervous angular Fraktur letters goose-step across pages of paper-thin platinum.

The

Faust

had been printed electrolytically and, with several thousand similarly worthwhile books, sealed in an argon-filled chamber and carefully lost, in 2012 A.D.; a very wealthy man’s legacy to the distant future.

In 2012 A.D., Polaris had been the pole star. Men eventually got to Polaris and built a small city on a frosty planet there. By that time, they weren’t dating by prophets’ births any more, but it would have been around 4900 A.D. The pole star by then, because of precession of the equinoxes, was a dim thing once called Gamma Cephei. The celestial pole kept reeling around, past Deneb and Vega and through barren patches of sky around Hercules and Draco; a patient clock but not the slowest one of use, and when it came back to the region of Polaris, then 26,000 years had passed and men had come back from the stars, to stay, and the book-filled chamber had shifted 130 meters on the floor of the Pacific, had rolled into a shallow trench, and eventually was buried in an underwater landslide.

The thirty-seventh time this slow clock ticked, men had moved the Pacific, not because they had to, and had found the chamber, opened it up, identified the books and carefully sealed them up again. Some things by then were more important to men than the accumulation of knowledge: in half of one more circle of the poles would come the millionth anniversary of the written word. They could wait a few millennia.

As the anniversary, as nearly as they could reckon it, approached, they caused to be born two individuals: Nine-hover (nominally female) and Three-phasing (nominally male). Three-phasing was born to learn how to read and speak. He was the first human being to study these skills in more than a quarter of a million years.

Three-phasing has read the first half of

Faust

forwards and, for amusement and exercise, is reading the second half backwards. He is singing as he reads, lisping.

“Fain’ Looee w’mun...wif all’r die-mun ringf...” He has not put in his teeth because they make his gums hurt.

Because he is a child of two hundred, he is polite when his father interrupts his reading and singing. His father’s “voice” is an arrangement of logic and aesthetic that appears in Three-phasing’s mind. The flavor is lost by translating into words:

“Three-phasing my son-ly atavism of tooth and vocal cord,” sarcastically in the reverent mode, “couldst tear thyself from objects of manifest symbol, and visit to share/help/learn, me?”

“?” he responds, meaning “with/with/of what?”

Withholding mode: “Concerning thee: past, future.”

He shuts the book without marking his place. It would never occur to him to mark his place, since he remembers perfectly the page he stops on, as well as every word preceding, as well as every event, no matter how trivial, that he has observed from the precise age of one year. In this respect, at least, he is normal.

He thinks the proper coordinates as he steps over the mover-transom, through a microsecond of black, and onto his father’s mover-transom, about four thousand kilometers away on a straight line through the crust and mantle of the earth.

Ritual mode: “As ever, father.” The symbol he uses for “father” is purposefully wrong, chiding. Crude biological connotation.

His father looks cadaverous and has in fact been dead twice. In the infant’s small-talk mode he asks, “From crude babblings of what sort have I torn your interest?”

“The tale called

Faust,

of a man so named, never satisfied with {symbol for slow but continuous accretion} of his knowledge and power; written in the language of Prussia.”

“Also depended-ing on this strange word of immediacy, your Prussian language?”

“As most, yes. The word of ‘to be’:

sein.

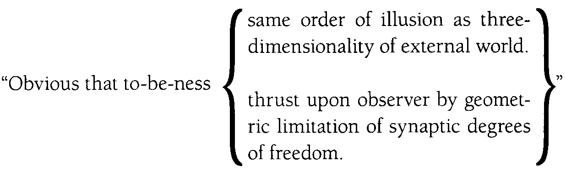

Very important illusion in this and related languages/cultures; that events happen at the ‘time’ of perception, infinitesimal midpoint between past and future.”

“Convenient illusion but retarding.”

“As we discussed 129 years ago, yes.” Three-phasing is impatient to get back to his reading, but adds:

“You always stick up for them.”

“I have great regard for what they accomplished with limited faculties and so short lives.” Stop beatin’ around the bush, Dad.

Tempus fugit,

eight to the bar. Did Mr. Handy Moves-dat-man-around-by-her-apron-strings, 20th-century American poet, intend cultural translation of

Lysistrata?

If so, inept. African were-beast legendry, yes.

Withholding mode (coy): “Your father stood with Nine-hover all morning.”

“,” broadcasts Three-phasing: well?

“The machine functions, perhaps inadequately.”

The young polyglot tries to radiate calm patience.

“Details I perceive you want; the idea yet excites you. You can never have satisfaction with your knowledge, either. What happened-s to the man in your Prussian book?”

“He lived-s one hundred years and died-s knowing that a man can never achieve true happiness, despite the appearance of success.”