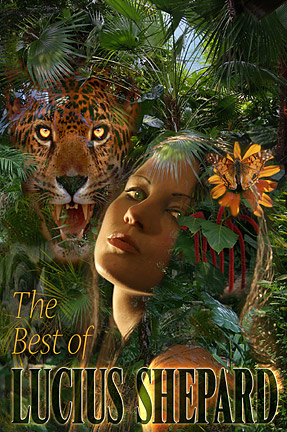

The Best of Lucius Shepard

Read The Best of Lucius Shepard Online

Authors: Lucius Shepard

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Collections & Anthologies

* *

* *

The Best of

Lucius Shepard

By Lucius Shepard

* * * *

THE

MAN WHO PAINTED THE DRAGON GRIAULE

*

* * *

The

Man Who Painted the Dragon Griaule

“Other than the Sichi Collection, Cattanay’s only

surviving works are to be found in the Municipal Gallery at Regensburg, a group

of eight oils-on-canvas, most notable among them being

Woman With Oranges

.

These paintings constitute his portion of a student exhibition hung some weeks

after he had left the city of his birth and travelled south to Teocinte, there

to present his proposal to the city fathers; it is unlikely he ever learned of

the disposition of his work, and even more unlikely that he was aware of the

general critical indifference with which it was received. Perhaps the most

interesting of the group to modern scholars, the most indicative as to Cattanay’s

later preoccupations, is the

Self Portrait

, painted at the age of

twenty-eight, a year before his departure.

“The

majority of the canvas is a richly varnished black in which the vague shapes of

floorboards are presented, barely visible. Two irregular slashes of gold cross

the blackness, and within these we can see a section of the artist’s thin

features and the shoulder panel of his shirt. The perspective given is that we

are looking down at the artist, perhaps through a tear in the roof, and that he

is looking up at us, squinting into the light, his mouth distorted by a grimace

born of intense concentration. On first viewing the painting, I was struck by

the atmosphere of tension that radiated from it. It seemed I was spying upon a

man imprisoned within a shadow having two golden bars, tormented by the

possibilities of light beyond the walls. And though this may be the reaction of

the art historian, not the less knowledgeable and therefore more trustworthy

response of the gallery-goer, it also seemed that this imprisonment was

self-imposed, that he could have easily escaped his confine; but that he had

realized a feeling of stricture was an essential fuel to his ambition, and so

had chained himself to this arduous and thoroughly unreasonable chore of perception…”

— from

Meric

Cattany: The Politics of Conception

by Reade Holland, Ph.D

1

IN 1853, IN A COUNTRY FAR TO THE SOUTH, in a world

separated from this one by the thinnest margin of possibility, a dragon named

Griaule dominated the region of the Carbonales Valley, a fertile area centring

upon the town of Teocinte and renowned for its production of silver, mahogany

and indigo. There were other dragons in those days, most dwelling on the rocky

islands west of Patagonia - tiny, irascible creatures, the largest of them no

bigger than a swallow. But Griaule was one of the great beasts who had ruled an

age. Over the centuries he had grown to stand 750 feet high at the mid-back,

and from the tip of his tail to his nose he was 6,000 feet long. (It should be

noted here that the growth of dragons was due not to caloric intake, but to the

absorption of energy derived from the passage of time.) Had it not been for a

miscast spell, Griaule would have died millennia before. The wizard entrusted

with the task of slaying him - knowing his own life would be forfeited as a

result of the magical backwash - had experienced a last-second twinge of fear,

and, diminished by this ounce of courage, the spell had flown a mortal inch

awry. Though the wizard’s whereabouts were unknown, Griaule had remained alive.

His heart had stopped, his breath stilled, but his mind continued to seethe, to

send forth the gloomy vibrations that enslaved all who stayed for long within

range of his influence.

This

dominance of Griaule’s was an elusive thing. The people of the valley

attributed their dour character to years of living under his mental shadow, yet

there were other regional populations who maintained a harsh face to the world

and had no dragon on which to blame the condition; they also attributed their

frequent raids against the neighbouring states to Griaule’s effect, claiming to

be a peaceful folk at heart - but again, was this not human nature? Perhaps the

most certifiable proof of Griaule’s primacy was the fact that despite a

standing offer of a fortune in silver to anyone who could kill him, no one had

succeeded. Hundreds of plans had been put forward, and all had failed, either

through inanition or impracticality. The archives of Teocinte were filled with

schematics for enormous steam-powered swords and other such improbable devices,

and the architects of these plans had every one stayed too long in the valley

and become part of the disgruntled populace. And so they went on with their

lives, coming and going, always returning, bound to the valley, until one

spring day in 1853, Meric Cattanay arrived and proposed that the dragon be

painted.

He was a

lanky young man with a shock of black hair and a pinched look to his cheeks; he

affected the loose trousers and shirt of a peasant, and waved his arms to make

a point. His eyes grew wide when listening, as if his brain were bursting with

illumination, and at times he talked incoherently about “the conceptual

statement of death by art”. And though the city fathers could not be sure,

though they allowed for the possibility that he simply had an unfortunate

manner, it seemed he was mocking them. All in all, he was not the sort they

were inclined to trust. But, because he had come armed with such a wealth of

diagrams and charts, they were forced to give him serious consideration.

“I don’t

believe Griaule will be able to perceive the menace in a process as subtle as

art,” Meric told them. “We’ll proceed as if we were going to illustrate him,

grace his side with a work of true vision, and all the while we’ll be poisoning

him with the paint.”

The city

fathers voiced their incredulity, and Meric waited impatiently until they

quieted. He did not enjoy dealing with these worthies. Seated at their long

table, sour-faced, a huge smudge of soot on the wall above their heads like an

ugly thought they were sharing, they reminded him of the Wine Merchants

Association in Regensburg, the time they had rejected his group portrait.

“Paint can

be deadly stuff,” he said after their muttering had died down. “Take vert

Veronese, for example. It’s derived from oxide of chrome and barium. Just a

whiff would make you keel over. But we have to go about it seriously, create a

real piece of art. If we just slap paint on his side, he might see through us.”

The first

step in the process, he told them, would be to build a tower of scaffolding,

complete with hoists and ladders, that would brace against the supraocular

plates above the dragon’s eye; this would provide a direct route to a

700-foot-square loading platform and base station behind the eye. He estimated

it would take 81,000 board feet of lumber, and a crew of ninety men should be

able to finish construction within five months. Ground crews accompanied by

chemists and geologists would search out limestone deposits (useful in priming

the scales) and sources of pigments, whether organic or minerals such as

azurite and hematite. Other teams would be set to scraping the dragon’s side

clean of algae, peeled skin, any decayed material, and afterwards would laminate

the surface with resins.

“It would be

easier to bleach him with quicklime,” he said. “But that way we lose the

discolourations and ridges generated by growth and age, and I think what we’ll

paint will be defined by those shapes. Anything else would look like a damn

tattoo!”

There would

be storage vats and mills: edge-runner mills to separate pigments from crude

ores, ball mills to powder the pigments, pug mills to mix them with oil. There

would be boiling vats and calciners — 15-foot-high furnaces used to produce

caustic lime for sealant solutions.

“We’ll build

most of them atop the dragon’s head for purposes of access,” he said. “On the

frontoparital plate.” He checked some figures. “By my reckoning, the plate’s

about 350 feet wide. Does that sound accurate?”

Most of the

city fathers were stunned by the prospect, but one managed a nod, and another

asked, “How long will it take for him to die?”

“Hard to

say,” came the answer. “Who knows how much poison he’s capable of absorbing. It

might just take a few years. But in the worst instance, within forty or fifty

years, enough chemicals will have seeped through the scales to have weakened

the skeleton, and he’ll fall in like an old barn.”

“Forty

years!” exclaimed someone. “Preposterous!”

“Or fifty.”

Meric smiled. “That way we’ll have time to finish the painting.” He turned and

walked to the window and stood gazing out at the white stone houses of

Teocinte. This was going to be the sticky part, but if he read them right, they

would not believe in the plan if it seemed too easy. They needed to feel they

were making a sacrifice, that they were nobly bound to a great labour. “If it

does take forty or fifty years,” he went on, “the project will drain your

resources. Timber, animal life, minerals. Everything will be used up by the

work. Your lives will be totally changed. But I guarantee you’ll be rid of

him.”

The city

fathers broke into an outraged babble.

“Do you

really want to kill him?” cried Meric, stalking over to them and planting his

fists on the table. “You’ve been waiting centuries for someone to come along

and chop off his head or send him up in a puff of smoke. That’s not going to

happen! There is no easy solution. But there is a practical one, an elegant

one. To use the stuff of the land he dominates to destroy him. It will

not

be easy, but you

will

be rid of him. And that’s what you want, isn’t

it?”