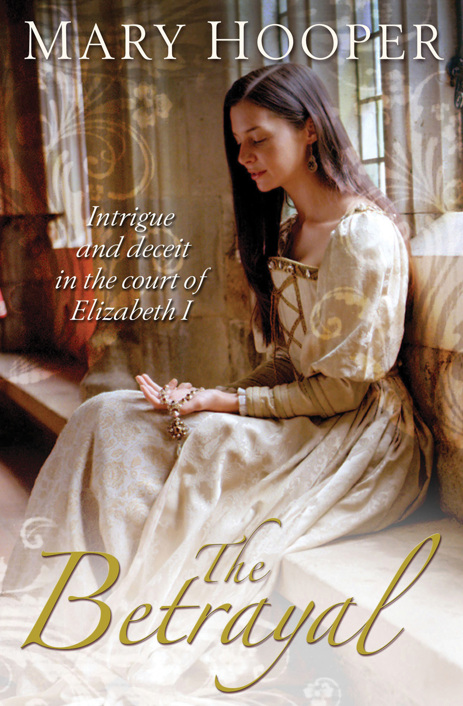

The Betrayal

Authors: Mary Hooper

MARY HOOPER

Some Historical Notes from the Author

At The Sign Of The Sugared Plum

The second week of January was so fearsome cold that hoar frost edged the bare twigs of the trees lining the lanes and even the deepest puddles iced over. Beth, Merryl and I, waiting endlessly with others on the turnpike road which ran from Richmond to London, pretended we were dragons to pass the time, huffing out our breath in great clouds of vapour.

We were waiting for Her Royal Majesty Queen Elizabeth and her court, who were leaving Richmond Palace that day for the Palace of Whitehall in London. They were moving to give Her Grace a change of scene, and also to ensure that Richmond Palace was aired and freshened after being occupied by hundreds of people for nigh on three months. On the roadway with us were scores of loyal neighbours and citizens, all of us mighty sorry to see her go. This wasn’t just because the Royal Court brought prosperity and vitality to the area,

but also because we loved having our beloved queen living in close proximity to us, knowing that at any moment she might be seen riding with a pack of hounds into the great park or glimpsed gliding downstream on the royal barge. We were privileged indeed to live, for at least some of each year, so close to the lady we all loved and revered.

Merryl sighed, tiring quickly of the dragon game. ‘Will she be much longer, Lucy? I’m so cold!’

‘Any minute now,’ I said. I crossed my fingers against the Devil catching me out in a lie. ‘I’m sure I hear the wagons rolling …’

I tucked Merryl’s shawl more snugly around her and told both children to march up and down like the queen’s soldiers in order to warm their toes. They sighed again, but were obedient girls and so, stamping furiously, they began marching along, cresting ridges of mud which had been hard-frozen into icy peaks and breaking them into powdery lumps.

‘How can she take this long to get ready when she has at least forty maidservants to help her?’ Merryl asked as she stamped.

‘About one maidservant for each garment!’ Beth said. ‘And have you thought that when she

does

come, she’ll go by us in a moment wrapped in so many furs that we may not even see who’s in the centre of them.’

‘I’m sure she will not,’ I said, ‘for Her Grace likes to be seen and admired by us. And even if she

is

too muffled in her ermines and her bearskins, there will be

many other grand ladies and gentlemen of the Court to set our eyes upon.’

As I spoke I looked down the road once more for any sign of the cavalcade. I spoke of other grand folk, but really I was thinking of one person in particular: Tomas, who was the queen’s fool and would be travelling with Her Grace’s trusty band of jesters, clowns and jugglers. Tomas was my special friend.

Friend

, I thought firmly, and not sweetheart, for I mustn’t let the one kiss there had been between us permit me to think there was any understanding. At least not yet. In time, though, I dreamed there might be, for I was sure that he liked and admired me.

‘We’ve seen all the gentlemen and ladies of the Court before, though,’ said Beth plaintively. ‘And anyway, the queen often comes to call on us and when she does we have her all to ourselves.’

‘Hush!’ I took a quick look around to see if anyone else had heard this, for some Mortlake folk were nervous about being in close proximity to those of us who lived in the house of the queen’s magician, thinking us all conjurers and dabblers in the black arts. The reality, however, was very different, for although I hadn’t been working as a nursemaid at the house for very long, it was obvious to me that Dr Dee was somewhat lacking in those dark skills said to be necessary for someone of his calling. He was supposed to be able to contact spirits – but once, failing to do this, had paid me two gold coins to pretend to be the wraith of a girl

who’d died. On another occasion I’d been taught – by trickery and sleight of hand – how to substitute base metal for gold so that it would look as if my master had found the secret of the philosopher’s stone. He was, without a doubt, tremendously skilled in languages, map-making and charting where the stars were positioned, but I’d not seen anything in the least bit magickal while I’d been working at his house.

Merryl frowned at her sister. Two years younger, she was a girl as dry and sensible as a dowager. ‘Her Grace is not

always

visiting,’ she corrected. ‘She came exactly twice last year. Once to ask about an elixir and once to ask Papa about the witch doll someone had …’

‘Hush,’ I said again. ‘You know your father doesn’t like you to speak about his work outside the house.’

Beth gave a great sigh and surveyed the distant road once more. ‘Perhaps she’s changed her moving day again.’

‘It’s packing up all those precious jewels that’s taking the time!’ a grimy farmer standing alongside us said with a chuckle. ‘I heard she had so much gold and so many gems as New Year gifts that she could have opened a shop and traded as a jeweller.’

I smiled and nodded by way of reply, knowing that the man spoke truly. This was because I’d been lucky enough to be at the palace on New Year’s Day and had seen the costly gifts piled and tumbled on the table, awaiting her attention.

I looked down the road now, surveying those waiting

to see Her Grace. They were mostly working folk: gardeners straight from Mortlake’s asparagus fields, two or three burly blacksmiths, brewers, lightermen and bargemen from the river, goodwives on their way to market, two stinking night-soil men (people were placing themselves a way off from these) and a fair sprinkling of apprentices, maidservants, cooks and housekeepers from the big houses. We’d all assembled on the roadway a few days previous to this: two days after Twelfth Night and the day the Court had been due to move, but then the message had spread down to us that there had been a change of plan and that they wouldn’t be travelling until this morning. Mistress Midge, who was cook and housekeeper at the Dee house, had elected not to come again, saying she’d got quite cold enough the previous time.