Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (21 page)

In an article inspired by Black called “The Decline of Elite Homicide,” the criminologist Mark Cooney shows that many lower-status people—the poor, the uneducated, the unmarried, and members of minority groups—are effectively stateless. Some make a living from illegal activities like drug dealing, gambling, selling stolen goods, and prostitution, so they cannot file lawsuits or call the police to enforce their interests in business disputes. In that regard they share their need for recourse to violence with certain

high

-status people, namely dealers in contraband such as Mafiosi, drug kingpins, and Prohibition rumrunners.

high

-status people, namely dealers in contraband such as Mafiosi, drug kingpins, and Prohibition rumrunners.

But another reason for their statelessness is that lower-status people and the legal system often live in a condition of mutual hostility. Black and Cooney report that in dealing with low-income African Americans, police “seem to vacillate between indifference and hostility, . . . reluctant to become involved in their affairs but heavy handed when they do so.”

59

Judges and prosecutors too “tend to be . . . uninterested in the disputes of low-status people, typically disposing of them quickly and, to the parties involved, with an unsatisfactory penal emphasis.”

60

Here is a Harlem police sergeant quoted by the journalist Heather MacDonald:

59

Judges and prosecutors too “tend to be . . . uninterested in the disputes of low-status people, typically disposing of them quickly and, to the parties involved, with an unsatisfactory penal emphasis.”

60

Here is a Harlem police sergeant quoted by the journalist Heather MacDonald:

Last weekend, a known neighborhood knucklehead hit a kid. In retaliation, the kid’s whole family shows up at the perp’s apartment. The victim’s sisters kick in the apartment door. But the knucklehead’s mother beat the shit out of the sisters, leaving them lying on the floor with blood coming from their mouths. The victim’s family was looking for a fight: I could charge them with trespass. The perp’s mother is eligible for assault three for beating up the opposing family. But all of them were street shit, garbage. They will get justice in their own way. I told them: “We can all go to jail, or we can call it a wash.” Otherwise, you’d have six bodies in prison for BS behavior. The district attorney would have been pissed. And none of them would ever show up in court.

61

Not surprisingly, lower-status people tend not to avail themselves of the law and may be antagonistic to it, preferring the age-old alternative of self-help justice and a code of honor. The police sergeant’s compliment about the kind of people he deals with in his precinct was returned by the young African Americans interviewed by the criminologist Deanna Wilkinson:

Reggie:

The cops working my neighborhood don’t belong working in my neighborhood. How you gonna send white cops to a black neighborhood to protect and serve? You can’t do that cause all they gonna see is the black faces that’s committing the crimes. They all look the same. The ones that’s not committing crimes looks like the niggas that is committing crimes and everybody is getting harassed.Dexter:

They make worser cause niggas [the police] was fuckin’ niggas [youth] up. They crooked theyself, you know what I mean? Them niggas [the police officers] would run up on the drug spot, take my drugs, they’ll sell that shit back on the street, so they could go rush-knock someone else.Quentin [speaking of a man who had shot his father]:

There’s a chance he could walk, what am I supposed to do? . . . If I lose my father, and they don’t catch this guy, I’m gonna get his family. That’s the way it works out here. That’s the way all this shit out here works. If you can’t get him, get them.... Everybody grow up with the shit, they want respect, they want to be the man.

62

The historical Civilizing Process, in other words, did not eliminate violence, but it did relegate it to the socioeconomic margins.

VIOLENCE AROUND THE WORLDThe Civilizing Process spread not only downward along the socioeconomic scale but outward across the geographic scale, from a Western European epicenter. We saw in figure 3–3 that England was the first to pacify itself, followed closely by Germany and the Low Countries. Figure 3–8 plots this outward ripple on maps of Europe in the late 19th and early 21st centuries.

FIGURE 3–8.

Geography of homicide in Europe, late 19th and early 21st centuries

Geography of homicide in Europe, late 19th and early 21st centuries

Sources:

Late 19th century (1880–1900): Eisner, 2003. The subdivision of Eisner’s“5.0 per 100.000” range into 5–10 and 10–30 was done in consultation with Eisner. Data for Montenegro based on data for Serbia. Early 21st century (mostly 2004). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2009; data were selected as in note 66.

Late 19th century (1880–1900): Eisner, 2003. The subdivision of Eisner’s“5.0 per 100.000” range into 5–10 and 10–30 was done in consultation with Eisner. Data for Montenegro based on data for Serbia. Early 21st century (mostly 2004). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2009; data were selected as in note 66.

In the late 1800s, Europe had a peaceable bull’s-eye in the northern industrialized countries (Great Britain, France, Germany, Denmark, and the Low Countries), bordered by slightly stroppier Ireland, Austria-Hungary, and Finland, surrounded in turn by still more violent Spain, Italy, Greece, and the Slavic countries. Today the peaceable center has swelled to encompass all of Western and Central Europe, but a gradient of lawlessness extending to Eastern Europe and the mountainous Balkans is still visible.

There are gradients within each of these countries as well: the hinterlands and mountains remained violent long after the urbanized and densely farmed centers had calmed down. Clan warfare was endemic to the Scottish highlands until the 18th century, and to Sardinia, Sicily, Montenegro, and other parts of the Balkans until the 20th.

63

It’s no coincidence that the two blood-soaked classics with which I began this book—the Hebrew Bible and the Homeric poems—came from peoples that lived in rugged hills and valleys.

63

It’s no coincidence that the two blood-soaked classics with which I began this book—the Hebrew Bible and the Homeric poems—came from peoples that lived in rugged hills and valleys.

What about the rest of the world? Though most European countries have kept statistics on homicide for a century or more, the same cannot be said for the other continents. Even today the police-blotter tallies that departments report to Interpol are often unreliable and sometimes incredible. Many governments feel that their degree of success in keeping their citizens from murdering each other is no one else’s business. And in parts of the developing world, warlords dress up their brigandage in the language of political liberation movements, making it hard to draw a line between casualties in a civil war and homicides from organized crime.

64

64

With those limitations in mind, let’s take a peek at the distribution of homicide in the world today. The most reliable data come from the World Health Organization (WHO), which uses public health records and other sources to estimate the causes of death in as many countries as possible.

65

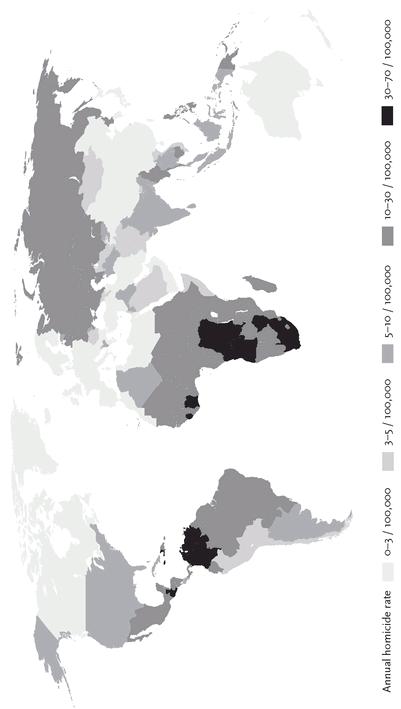

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has supplemented these data with high and low estimates for every country in the world. Figure 3–9 plots these numbers for 2004 (the year covered in the office’s most recent report) on a map of the world.

66

The good news is that the median national homicide rate among the world’s countries in this dataset is 6 per 100,000 per year. The overall homicide rate for the entire world, ignoring the division into countries, was estimated by the WHO in 2000 as 8.8 per 100,000 per year.

67

Both estimates compare favorably to the triple-digit values for pre-state societies and the double-digit values for medieval Europe.

65

The UN Office on Drugs and Crime has supplemented these data with high and low estimates for every country in the world. Figure 3–9 plots these numbers for 2004 (the year covered in the office’s most recent report) on a map of the world.

66

The good news is that the median national homicide rate among the world’s countries in this dataset is 6 per 100,000 per year. The overall homicide rate for the entire world, ignoring the division into countries, was estimated by the WHO in 2000 as 8.8 per 100,000 per year.

67

Both estimates compare favorably to the triple-digit values for pre-state societies and the double-digit values for medieval Europe.

The map shows that Western and Central Europe make up the least violent region in the world today. Among the other states with credible low rates of homicide are those carved out of the British Empire, such as Australia, New Zealand, Fiji, Canada, the Maldives, and Bermuda. Another former British colony defies the pattern of English civility; we will examine this strange country in the next section.

Several Asian countries have low homicide rates as well, particularly those that have adopted Western models, such as Japan, Singapore, and Hong Kong. Also reporting a low homicide rate is China (2.2 per 100,000). Even if we take the data from this secretive state at face value, in the absence of time-series data we have no way of knowing whether it is best explained by millennia of centralized government or by the authoritarian nature of its current regime. Established autocracies (including many Islamic states) keep close tabs on their citizens and punish them surely and severely when they step out of line; that’s why we call them “police states.” Not surprisingly, they tend to have low rates of violent crime. But I can’t resist an anecdote which suggests that China, like Europe, underwent a civilizing process over the long term. Elias noted that knife taboos, which accompanied the reduction of violence in Europe, have been taken one step further in China. For centuries in China, knives have been reserved for the chef in the kitchen, where he cuts the food into bite-sized pieces. Knives are banned from the dining table altogether. “The Europeans are barbarians,” Elias quotes them as saying. “They eat with swords.”

68

68

FIGURE 3-9, Geography of homicide in the world, 2004

Sources

: Data from UN Office on Drugs and Crime, international homicide statistics 2004 ; see note 66. Estimate for Taiwan from China (Taiwan), Republic of, Department of Statistics, Ministry, of the Interior. 2000.

: Data from UN Office on Drugs and Crime, international homicide statistics 2004 ; see note 66. Estimate for Taiwan from China (Taiwan), Republic of, Department of Statistics, Ministry, of the Interior. 2000.

What about the other parts of the world? The criminologist Gary LaFree and the sociologist Orlando Patterson have shown that the relationship between crime and democratization is an inverted U. Established democracies are relatively safe places, as are established autocracies, but emerging democracies and semi-democracies (also called anocracies) are often plagued by violent crime and vulnerable to civil war, which sometimes shade into each other.

69

The most crime-prone regions in the world today are Russia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America. Many of them have corrupt police forces and judicial systems which extort bribes out of criminals and victims alike and dole out protection to the highest bidder. Some, like Jamaica (33.7), Mexico (11.1), and Colombia (52.7), are racked by drug-funded militias that operate beyond the reach of the law. Over the past four decades, as drug trafficking has increased, their rates of homicide have soared. Others, like Russia (29.7) and South Africa (69), may have undergone decivilizing processes in the wake of the collapse of their former governments.

69

The most crime-prone regions in the world today are Russia, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Latin America. Many of them have corrupt police forces and judicial systems which extort bribes out of criminals and victims alike and dole out protection to the highest bidder. Some, like Jamaica (33.7), Mexico (11.1), and Colombia (52.7), are racked by drug-funded militias that operate beyond the reach of the law. Over the past four decades, as drug trafficking has increased, their rates of homicide have soared. Others, like Russia (29.7) and South Africa (69), may have undergone decivilizing processes in the wake of the collapse of their former governments.

The decivilizing process has also racked many of the countries that switched from tribal ways to colonial rule and then suddenly to independence, such as those in sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea (15.2). In her article “From Spears to M-16s,” the anthropologist Polly Wiessner examines the historical trajectory of violence among the Enga, a New Guinean tribal people. She begins with an excerpt from the field notes of an anthropologist who worked in their region in 1939:

We were now in the heart of the Lai Valley, one of the most beautiful in New Guinea, if not in the world. Everywhere were fine well-laid out garden plots, mostly of sweet potato and groves of casuarinas. Well-cut and graded roads traversed the countryside, and small parks . . . dotted the landscape, which resembled a huge botanical garden.

She compares it to her own diary entry from 2004:

The Lai Valley is a virtual wasteland—as the Enga say, “cared for by the birds, snakes, and rats.” Houses are burned to ash, sweet potato gardens overgrown with weeds, and trees razed to jagged stumps. In the high forest, warfare rages on, fought by “Rambos” with shotguns and high-powered rifles taking the lives of many. By the roadside where markets bustled just a few years before, there is an eerie emptiness.

70

The Enga were never what you could call a peaceable people. One of their tribes, the Mae Enga, are represented by a bar in figure 2–3: it shows that they killed each other in warfare at an annual rate of about 300 per 100,000, dwarfing the worst rates we have been discussing in this chapter. All the usual Hobbesian dynamics played out: rape and adultery, theft of pigs and land, insults, and of course, revenge, revenge, and more revenge. Still, the Enga were conscious of the waste of war, and some of the tribes took steps, intermittently successful, to contain it. For example, they developed Geneva-like norms that outlawed war crimes such as mutilating bodies or killing negotiators. And though they sometimes were drawn into destructive wars with other villages and tribes, they worked to control the violence within their own communities. Every human society is faced with a conflict of interest between the younger men, who seek dominance (and ultimately mating opportunities) for themselves, and the older men, who seek to minimize internecine damage within their extended families and clans. The Enga elders forced obstreperous young men into “bachelor cults,” which encouraged them to control their vengeful impulses with the help of proverbs like “The blood of a man does not wash off easily” and “You live long if you plan the death of a pig, but not if you plan the death of a person.”

71

And consonant with the other civilizing elements in their culture, they had norms of propriety and cleanliness, which Wiessner described to me in an e-mail:

71

And consonant with the other civilizing elements in their culture, they had norms of propriety and cleanliness, which Wiessner described to me in an e-mail:

The Enga cover themselves with raincapes when they defecate, so as not to offend anybody, even the sun. For a man to stand by the road, turn his back and pee is unthinkably crude. They wash their hands meticulously before they cook food; they are extremely modest about covering genitals, and so on. Not so great with snot.

Other books

A Raucous Time (The Celtic Cousins' Adventures) by Hughes, Julia

SEAL Encounter (SEAL Brotherhood) by Hamilton, Sharon

The Witch Queen's Secret by Anna Elliott

Pyg by Russell Potter

Red or Dead by David Peace

The Day Of The Wave by Wicks, Becky

Hold Tight by Harlan Coben

Dragon Princess by S. Andrew Swann

Make Me Weak (Make Me #1) by Megan Noelle