The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (52 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

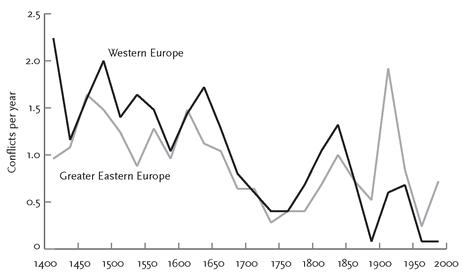

Let’s start by simply counting the conflicts—not just the wars embroiling great powers, but deadly quarrels great and small. These tallies, plotted in figure 5–17, offer an independent view of the history of war in Europe.

Once again we see a decline in one of the dimensions of armed conflict: how often they break out. When the story begins in 1400, European states were starting conflicts at a rate of more than three a year. That rate has caromed downward to virtually none in Western Europe and to less than one conflict per year in Eastern Europe. Even that bounce is a bit misleading, because half of the conflicts were in countries that are coded in the dataset as “Europe” only because they were once part of the Ottoman or Soviet empire; today they are usually classified as Middle Eastern or Central and South Asian (for example, conflicts in Turkey, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Dagestan, and Armenia).

86

The other Eastern European conflicts were in former republics of Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union. These regions—Yugoslavia, Russia/USSR, and Turkey—were also responsible for the spike of European conflicts in the first quarter of the 20th century.

86

The other Eastern European conflicts were in former republics of Yugoslavia or the Soviet Union. These regions—Yugoslavia, Russia/USSR, and Turkey—were also responsible for the spike of European conflicts in the first quarter of the 20th century.

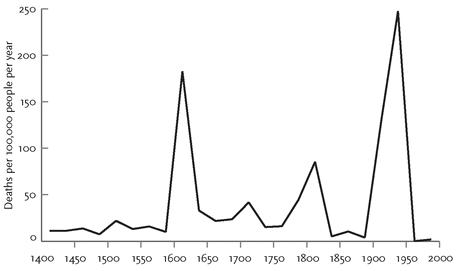

What about the human toll of the conflicts? Here is where the capaciousness of the Conflict Catalog comes in handy. The power-law distribution tells us that the biggest of the great power wars should account for the lion’s share of the deaths from all wars—at least, from all wars that exceed the thousand-death cutoff, which make up the data I have plotted so far. But Richardson alerted us to the possibility that a large number of smaller conflicts missed by traditional histories and datasets could, in theory, pile up into a substantial number of additional deaths (the gray bars in figure 5–11). The Conflict Catalog is the first long-term dataset that reaches down into that gray area and tries to list the skirmishes, riots, and massacres that fall beneath the traditional military horizon (though of course many more in the earlier centuries may never have been recorded). Unfortunately the catalog is a work in progress, and at present fewer than half the conflicts have fatality figures attached to them. Until it is completed, we can get a crude glimpse of the trajectory of conflict deaths in Europe by filling in the missing values using the median of the death tolls from that quarter-century. Brian Atwood and I have interpolated these values, added up the direct and indirect deaths from conflicts of all types and sizes, divided them by the population of Europe in each period, and plotted them on a linear scale.

87

Figure 5–18 presents this maximalist (albeit tentative) picture of the history of violent conflict in Europe:

87

Figure 5–18 presents this maximalist (albeit tentative) picture of the history of violent conflict in Europe:

FIGURE 5–17.

Conflicts per year in greater Europe, 1400–2000

Conflicts per year in greater Europe, 1400–2000

Sources:

Conflict Catalog, Brecke, 1999; Long & Brecke, 2003. The conflicts are aggregated over 25-year periods and include interstate and civil wars, genocides, insurrections, and riots. “Western Europe” includes the territories of the present-day U.K., Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. “Eastern Europe” includes the territories of the present-day Cyprus, Finland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, the republics formerly making up Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey (both Europe and Asia), Russia (Europe), Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and other Caucasus republics.

Conflict Catalog, Brecke, 1999; Long & Brecke, 2003. The conflicts are aggregated over 25-year periods and include interstate and civil wars, genocides, insurrections, and riots. “Western Europe” includes the territories of the present-day U.K., Ireland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Spain, Portugal, and Italy. “Eastern Europe” includes the territories of the present-day Cyprus, Finland, Poland, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania, the republics formerly making up Yugoslavia, Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Turkey (both Europe and Asia), Russia (Europe), Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and other Caucasus republics.

The scaling by population size did not eliminate an overall upward trend through 1950, which shows that Europe’s ability to kill people outpaced its ability to breed more of them. But what really pops out of the graph are three hemoclysms. Other than the quarter-century containing World War II, the most deadly time to have been alive in Europe was during the Wars of Religion in the early 17th century, followed by the quarter with World War I, then the period of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

FIGURE 5–18.

Rate of death in conflicts in greater Europe, 1400–2000

Rate of death in conflicts in greater Europe, 1400–2000

Sources:

Conflict Catalog, Brecke, 1999; Long & Brecke, 2003. Figures are from the “Total Fatalities” column, aggregated over 25-year periods. Redundant entries were eliminated. Missing entries were filled in with the median for that quarter-century. Historical population estimates are from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, taken at the end of the quarter-century. “Europe” is defined as in figure 5–17.

Conflict Catalog, Brecke, 1999; Long & Brecke, 2003. Figures are from the “Total Fatalities” column, aggregated over 25-year periods. Redundant entries were eliminated. Missing entries were filled in with the median for that quarter-century. Historical population estimates are from McEvedy & Jones, 1978, taken at the end of the quarter-century. “Europe” is defined as in figure 5–17.

The career of organized violence in Europe, then, looks something like this. There was a low but steady baseline of conflicts from 1400 to 1600, followed by the bloodbath of the Wars of Religion, a bumpy decline through 1775 followed by the French troubles, a noticeable lull in the middle and late 19th century, and then, after the 20th-century Hemoclysm, the unprecedented ground-hugging levels of the Long Peace.

How can we make sense of the various slow drifts and sudden lurches in violence during the past half-millennium among the great powers and in Europe? We have reached the point at which statistics must hand the baton over to narrative history. In the next sections I’ll tell the story behind the graphs by combining the numbers from the conflict-counters with the narratives from historians and political scientists such as David Bell, Niall Ferguson, Azar Gat, Michael Howard, John Keegan, Evan Luard, John Mueller, James Payne, and James Sheehan.

Here is a preview. Think of the zigzags in figure 5–18 as a composite of four currents. Modern Europe began in a Hobbesian state of frequent but small wars. The wars became fewer in number as political units became consolidated into larger states. At the same time the wars that did occur were becoming more lethal, because of a military revolution that created larger and more effective armies. Finally, in different periods European countries veered between totalizing ideologies that subordinated individual people’s interests to a utopian vision and an Enlightenment humanism that elevated those interests as the ultimate value.

THE HOBBESIAN BACKGROUND AND THE AGES OF DYNASTIES AND RELIGIONSThe backdrop of European history during most of the past millennium is everpresent warring. Carried over from the knightly raiding and feuding in medieval times, the wars embroiled every kind of political unit that emerged in the ensuing centuries.

The sheer number of European wars is mind-boggling. Brecke has compiled a prequel to the Conflict Catalog which lists 1,148 conflicts from 900 CE to 1400 CE, and the catalog itself lists another 1,166 from 1400 CE to the present—about two new conflicts a year for eleven hundred years.

88

The vast majority of these conflicts, including most of the major wars involving great powers, are outside the consciousness of all but the most assiduous historians. To take some random examples, the Dano-Swedish War (1516–25), the Schmalkaldic War (1546–47), the Franco-Savoian War (1600–1601), the Turkish-Polish War (1673–76), the War of Julich Succession (1609–10), and the Austria-Sardinia War (1848–49) elicit blank stares from most educated people.

89

88

The vast majority of these conflicts, including most of the major wars involving great powers, are outside the consciousness of all but the most assiduous historians. To take some random examples, the Dano-Swedish War (1516–25), the Schmalkaldic War (1546–47), the Franco-Savoian War (1600–1601), the Turkish-Polish War (1673–76), the War of Julich Succession (1609–10), and the Austria-Sardinia War (1848–49) elicit blank stares from most educated people.

89

Warring was not just prevalent in practice but accepted in theory. Howard notes that among the ruling classes, “Peace was regarded as a brief interval between wars,” and war was “an almost automatic activity, part of the natural order of things.”

90

Luard adds that while many battles in the 15th and 16th centuries had moderately low casualty rates, “even when casualties were high, there is little evidence that they weighed heavily with rulers or military commanders. They were seen, for the most part, as the inevitable price of war, which in itself was honourable and glorious.”

91

90

Luard adds that while many battles in the 15th and 16th centuries had moderately low casualty rates, “even when casualties were high, there is little evidence that they weighed heavily with rulers or military commanders. They were seen, for the most part, as the inevitable price of war, which in itself was honourable and glorious.”

91

What were they fighting over? The motives were the “three principal causes of quarrel” identified by Hobbes: predation (primarily of land), preemption of predation by others, and credible deterrence or honor. The principal difference between European wars and the raiding and feuding of tribes, knights, and warlords was that the wars were carried out by organized political units rather than by individuals or clans. Conquest and plunder were the principal means of upward mobility in the centuries when wealth resided in land and resources rather than in commerce and innovation. Nowadays ruling a dominion doesn’t strike most of us as an appealing career choice. But the expression “to live like a king” reminds us that centuries ago it was the main route to amenities like plentiful food, comfortable shelter, pretty objects, entertainment on demand, and children who survived their first year of life. The perennial nuisance of royal bastards also reminds us that a lively sex life was a perquisite of European kings no less than of harem-holding sultans, with “serving maids” a euphemism for concubines.

92

92

But what the leaders sought was not just material rewards but a spiritual need for dominance, glory, and grandeur—the bliss of contemplating a map and seeing more square inches tinted in the color that represents your dominion than someone else’s. Luard notes that even when rulers had little genuine authority over their titular realms, they went to war for “the theoretical right of overlordship: who owed allegiance to whom and for which territories.”

93

Many of the wars were pissing contests. Nothing was at stake but the willingness of one leader to pay homage to another in the form of titles, courtesies, and seating arrangements. Wars could be triggered by symbolic affronts such as a refusal to dip a flag, to salute colors, to remove heraldic symbols from a coat of arms, or to follow protocols of ambassadorial precedence.

94

93

Many of the wars were pissing contests. Nothing was at stake but the willingness of one leader to pay homage to another in the form of titles, courtesies, and seating arrangements. Wars could be triggered by symbolic affronts such as a refusal to dip a flag, to salute colors, to remove heraldic symbols from a coat of arms, or to follow protocols of ambassadorial precedence.

94

Though the motive to lead a dominant political bloc was constant through European history, the definition of the blocs changed, and with it the nature and extent of the fighting. In

War in International Society

, the most systematic attempt to combine a dataset of war with narrative history, Luard proposes that the sweep of armed conflict in Europe may be divided into five “ages,” each defined by the nature of the blocs that fought for dominance. In fact Luard’s ages are more like overlapping strands in a rope than boxcars on a track, but if we keep that in mind, his scheme helps to organize the major historical shifts in war.

War in International Society

, the most systematic attempt to combine a dataset of war with narrative history, Luard proposes that the sweep of armed conflict in Europe may be divided into five “ages,” each defined by the nature of the blocs that fought for dominance. In fact Luard’s ages are more like overlapping strands in a rope than boxcars on a track, but if we keep that in mind, his scheme helps to organize the major historical shifts in war.

Luard calls the first of his ages, which ran from 1400 to 1559, the Age of Dynasties. In this epoch, royal “houses,” or extended coalitions based on kinship, vied for control of European turfs. A little biology shows why the idea of basing leadership on inheritance is a recipe for endless wars of succession.

Rulers always face the dilemma of how to reconcile their thirst for everlasting power with an awareness of their own mortality. A natural solution is to designate an offspring, usually a firstborn son, as a successor. Not only do people think of their genetic progeny as an extension of themselves, but filial affection ought to inhibit any inclination of the successor to hurry things along with a little regicide. This would solve the succession problem in a species in which an organism could bud off an adult clone of himself shortly before he died. But many aspects of the biology of

Homo sapiens

confound the scheme.

Homo sapiens

confound the scheme.

Other books

Look After Me by Elena Matthews

Peril in Paperback by Kate Carlisle

When Love Intrudes (When the Mission Ends) by Snow, Christi

Phantom by L. J. Smith

Miracles and Massacres by Glenn Beck

The Hounds of the Morrigan by Pat O'Shea

Escape from Shanghai by Paul Huang

Infernal Sky by Dafydd ab Hugh

The Alien Artifact 9 (Novelette) by V Bertolaccini

Rough Ride by Laura Baumbach