The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (82 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Social History, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Criminology

Violence is sanctioned in the Islamic world not just by religious superstition but by a hyperdeveloped culture of honor. The political scientists Khaled Fattah and K. M. Fierke have documented how a “discourse of humiliation” runs through the ideology of Islamist organizations.

251

A sweeping litany of affronts—the Crusades, the history of Western colonization, the existence of Israel, the presence of American troops on Arabian soil, the underperformance of Islamic countries—are taken as insults to Islam and used to license indiscriminate vengeance against members of the civilization they hold responsible, together with Muslim leaders of insufficient ideological purity. The radical fringe of Islam harbors an ideology that is classically genocidal: history is seen as a violent struggle that will culminate in the glorious subjugation of an irredeemably evil class of people. Spokesmen for Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Iranian regime have demonized enemy groups (Zionists, infidels, crusaders, polytheists), spoken of a millennial cataclysm that would usher in a utopia, and justified the killing of entire categories of people such as Jews, Americans, and those felt to insult Islam.

252

251

A sweeping litany of affronts—the Crusades, the history of Western colonization, the existence of Israel, the presence of American troops on Arabian soil, the underperformance of Islamic countries—are taken as insults to Islam and used to license indiscriminate vengeance against members of the civilization they hold responsible, together with Muslim leaders of insufficient ideological purity. The radical fringe of Islam harbors an ideology that is classically genocidal: history is seen as a violent struggle that will culminate in the glorious subjugation of an irredeemably evil class of people. Spokesmen for Al Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and the Iranian regime have demonized enemy groups (Zionists, infidels, crusaders, polytheists), spoken of a millennial cataclysm that would usher in a utopia, and justified the killing of entire categories of people such as Jews, Americans, and those felt to insult Islam.

252

The historian Bernard Lewis is not the only one who has asked, “What went wrong?” In 2002 a committee of Arab intellectuals under the auspices of the United Nations published the candid

Arab Human Development Report

, said to be “written by Arabs for Arabs.”

253

The authors documented that Arab nations were plagued by political repression, economic backwardness, oppression of women, widespread illiteracy, and a self-imposed isolation from the world of ideas. At the time of the report, the entire Arab world exported fewer manufactured goods than the Philippines, had poorer Internet connectivity than sub-Saharan Africa, registered 2 percent as many patents per year as South Korea, and translated about a fifth as many books into Arabic as Greece translates into Greek.

254

Arab Human Development Report

, said to be “written by Arabs for Arabs.”

253

The authors documented that Arab nations were plagued by political repression, economic backwardness, oppression of women, widespread illiteracy, and a self-imposed isolation from the world of ideas. At the time of the report, the entire Arab world exported fewer manufactured goods than the Philippines, had poorer Internet connectivity than sub-Saharan Africa, registered 2 percent as many patents per year as South Korea, and translated about a fifth as many books into Arabic as Greece translates into Greek.

254

It wasn’t always that way. During the Middle Ages, Islamic civilization was unquestionably more refined than Christendom. While Europeans were applying their ingenuity to the design of instruments of torture, Muslims were preserving classical Greek culture, absorbing the knowledge of the civilizations of India and China, and advancing astronomy, architecture, cartography, medicine, chemistry, physics, and mathematics. Among the symbolic legacies of this age are the “Arabic numbers” (adapted from India) and loan words such as

alcohol, algebra, alchemy, alkali, azimuth, alembic,

and

algorithm

. Just as the West had to come from behind to overtake Islam in science, so it was a laggard in human rights. Lewis notes:

alcohol, algebra, alchemy, alkali, azimuth, alembic,

and

algorithm

. Just as the West had to come from behind to overtake Islam in science, so it was a laggard in human rights. Lewis notes:

In most tests of tolerance, Islam, both in theory and in practice, compares unfavorably with the Western democracies as they have developed during the last two or three centuries, but very favorably with most other Christian and post-Christian societies and regimes. There is nothing in Islamic history to compare with the emancipation, acceptance, and integration of otherbelievers and non-believers in the West; but equally, there is nothing in Islamic history to compare with the Spanish expulsion of Jews and Muslims, the Inquisition, the

Auto da fé’s

, the wars of religion, not to speak of more recent crimes of commission and acquiescence.

255

Why did Islam blow its lead and fail to have an Age of Reason, an Enlightenment, and a Humanitarian Revolution? Some historians point to bellicose passages in the Koran, but compared to our own genocidal scriptures, they are nothing that some clever exegesis and evolving norms couldn’t spindoctor away.

Lewis points instead to the historical lack of separation between mosque and state. Muhammad was not just a spiritual leader but a political and military one, and only recently have any Islamic states had the concept of a distinction between the secular and the sacred. With every potential intellectual contribution filtered through religious spectacles, opportunities for absorbing and combining new ideas were lost. Lewis recounts that while works in philosophy and mathematics had been translated from classical Greek into Arabic, works of poetry, drama, and history were not. And while Muslims had a richly developed history of their own civilization, they were incurious about their Asian, African, and European neighbors and about their own pagan ancestors. The Ottoman heirs to classical Islamic civilization resisted the adoption of mechanical clocks, standardized weights and measures, experimental science, modern philosophy, translations of poetry and fiction, the financial instruments of capitalism, and perhaps most importantly, the printing press. (Arabic was the language in which the Koran was written, so printing it was considered an act of desecration.)

256

In chapter 4 I speculated that the Humanitarian Revolution in Europe was catalyzed by a literate cosmopolitanism, which expanded people’s circle of empathy and set up a marketplace of ideas from which a liberal humanism could emerge. Perhaps the dead hand of religion impeded the flow of new ideas into the centers of Islamic civilization, locking it into a relatively illiberal stage of development. As if to prove the speculation correct, in 2010 the Iranian government restricted the number of university students who would be admitted to programs in the humanities, because, according to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khameini, study of the humanities “promotes skepticism and doubt in religious principles and beliefs.”

257

256

In chapter 4 I speculated that the Humanitarian Revolution in Europe was catalyzed by a literate cosmopolitanism, which expanded people’s circle of empathy and set up a marketplace of ideas from which a liberal humanism could emerge. Perhaps the dead hand of religion impeded the flow of new ideas into the centers of Islamic civilization, locking it into a relatively illiberal stage of development. As if to prove the speculation correct, in 2010 the Iranian government restricted the number of university students who would be admitted to programs in the humanities, because, according to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khameini, study of the humanities “promotes skepticism and doubt in religious principles and beliefs.”

257

Whatever the historical reasons, a large chasm appears to separate Western and Islamic cultures today. According to a famous theory from the political scientist Samuel Huntington, the chasm has brought us to a new age in the history of the world: the clash of civilizations. “In Eurasia the great historic fault lines between civilizations are once more aflame,” he wrote. “This is particularly true along the boundaries of the crescent-shaped Islamic bloc of nations, from the bulge of Africa to Central Asia. Violence also occurs between Muslims, on the one hand, and Orthodox Serbs in the Balkans, Jews in Israel, Hindus in India, Buddhists in Burma and Catholics in the Philippines. Islam has bloody borders.”

258

258

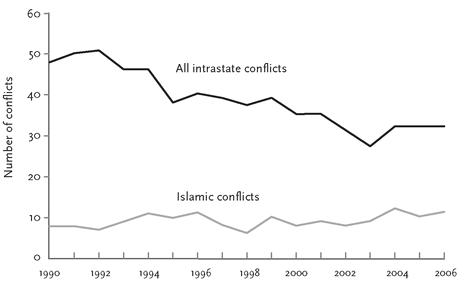

Though the dramatic notion of a clash of civilizations became popular among pundits, few scholars in international studies take it seriously. Too large a proportion of the world’s bloodshed takes place within and between Islamic countries (for example, Iraq’s war with Iran in the 1980s, and its invasion of Kuwait in 1990), and too large a proportion takes place within and between non-Islamic countries, for the civilizational fault line to be an accurate summary of violence in the world today. Also, as Nils Petter Gleditsch and Halvard Buhaug have pointed out, even though an increasing

proportion

of the world’s armed conflicts have involved Islamic countries and insurgencies over the past two decades (from 20 to 38 percent), it’s not because those conflicts have increased in

number

. As figure 6–12 shows, Islamic conflicts continued at about the same rate while the rest of the world got more peaceful, the phenomenon I have been calling the New Peace.

proportion

of the world’s armed conflicts have involved Islamic countries and insurgencies over the past two decades (from 20 to 38 percent), it’s not because those conflicts have increased in

number

. As figure 6–12 shows, Islamic conflicts continued at about the same rate while the rest of the world got more peaceful, the phenomenon I have been calling the New Peace.

Most important, the entire concept of “Islamic civilization” does a disservice to the 1.3 billion men and women who call themselves Muslims, living in countries as diverse as Mali, Nigeria, Morocco, Turkey, Saudi Arabia, Bangladesh, and Indonesia. And cutting across the divide of the Islamic world into continents and countries is another divide that is even more critical. Westerners tend to know Muslims through two dubious exemplars: the fanatics who grab headlines with their fatwas and jihads, and the oil-cursed autocrats who rule over them. The beliefs of the hitherto silent (and frequently silenced) majority make less of a contribution to our stereotypes. Can 1.3 billion Muslims really be untouched by the liberalizing tide that has swept the rest of the world in recent decades?

Part of the answer may be found in a massive Gallup poll conducted between 2001 and 2007 on the attitudes of Muslims in thirty-five countries representing 90 percent of the world’s Islamic population.

259

The results confirm that most Islamic states will not become secular liberal democracies anytime soon. Majorities of Muslims in Egypt, Pakistan, Jordan, and Bangladesh told the pollsters that Sharia, the principles behind Islamic law, should be the only source of legislation in their countries, and majorities in most of the countries said it should be at least one of the sources. On the other hand, a majority of Americans believe that the Bible should be one of the sources of legislation, and presumably they don’t mean that people who work on Sunday should be stoned to death. Religion thrives on woolly allegory, emotional commitments to texts that no one reads, and other forms of benign hypocrisy. Like Americans’ commitment to the Bible, most Muslims’ commitment to Sharia is more a symbolic affiliation with moral attitudes they associate with the best of their culture than a literal desire to see adulteresses stoned to death. In practice, creative and expedient readings of Sharia for liberal ends have often prevailed against the oppressive fundamentalist readings. (The Nigerian woman, for example, was never executed.) Presumably that is why most Muslims see no contradiction between Sharia and democracy. Indeed, despite their professed affection for the idea of Sharia, a large majority believe that religious leaders should have no direct role in drafting their country’s constitution.

259

The results confirm that most Islamic states will not become secular liberal democracies anytime soon. Majorities of Muslims in Egypt, Pakistan, Jordan, and Bangladesh told the pollsters that Sharia, the principles behind Islamic law, should be the only source of legislation in their countries, and majorities in most of the countries said it should be at least one of the sources. On the other hand, a majority of Americans believe that the Bible should be one of the sources of legislation, and presumably they don’t mean that people who work on Sunday should be stoned to death. Religion thrives on woolly allegory, emotional commitments to texts that no one reads, and other forms of benign hypocrisy. Like Americans’ commitment to the Bible, most Muslims’ commitment to Sharia is more a symbolic affiliation with moral attitudes they associate with the best of their culture than a literal desire to see adulteresses stoned to death. In practice, creative and expedient readings of Sharia for liberal ends have often prevailed against the oppressive fundamentalist readings. (The Nigerian woman, for example, was never executed.) Presumably that is why most Muslims see no contradiction between Sharia and democracy. Indeed, despite their professed affection for the idea of Sharia, a large majority believe that religious leaders should have no direct role in drafting their country’s constitution.

FIGURE 6–12.

Islamic and world conflicts, 1990–2006

Islamic and world conflicts, 1990–2006

Source:

Data from Gleditsch, 2008. “Islamic conflicts” involve Muslim countries or Islamic opposition movements or both. Data assembled by Halvard Buhaug from the UCDP⁄ PRIO conflict dataset and his own coding of Islamic conflicts.

Data from Gleditsch, 2008. “Islamic conflicts” involve Muslim countries or Islamic opposition movements or both. Data assembled by Halvard Buhaug from the UCDP⁄ PRIO conflict dataset and his own coding of Islamic conflicts.

Though most Muslims distrust the United States, it may not be out of a general animus toward the West or a hostility to democratic principles. Many Muslims feel the United States does

not

want to spread democracy in the Muslim world, and they have a point: the United States, after all, has supported autocratic regimes in Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, rejected the election of Hamas in the Palestinian territories, and in 1953 helped overthrow the democratically elected Mossadegh in Iran. France and Germany are viewed more favorably, and between 20 and 40 percent say they admire the “fair political system, respect for human values, liberty, and equality” of Western culture. More than 90 percent would guarantee freedom of speech in their nation’s constitution, and large numbers also support freedom of religion and freedom of assembly. Substantial majorities of both sexes in all the major Muslim countries say that women should be allowed to vote without influence from men, to work at any job, to enjoy the same legal rights as men, and to serve in the highest levels of government. And as we have seen, overwhelming majorities of the Muslim world reject the violence of Al Qaeda. Only 7 percent of the Gallup respondents approved the 9/11 attacks, and that was before Al Qaeda’s popularity cratered in 2007.

not

want to spread democracy in the Muslim world, and they have a point: the United States, after all, has supported autocratic regimes in Egypt, Jordan, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, rejected the election of Hamas in the Palestinian territories, and in 1953 helped overthrow the democratically elected Mossadegh in Iran. France and Germany are viewed more favorably, and between 20 and 40 percent say they admire the “fair political system, respect for human values, liberty, and equality” of Western culture. More than 90 percent would guarantee freedom of speech in their nation’s constitution, and large numbers also support freedom of religion and freedom of assembly. Substantial majorities of both sexes in all the major Muslim countries say that women should be allowed to vote without influence from men, to work at any job, to enjoy the same legal rights as men, and to serve in the highest levels of government. And as we have seen, overwhelming majorities of the Muslim world reject the violence of Al Qaeda. Only 7 percent of the Gallup respondents approved the 9/11 attacks, and that was before Al Qaeda’s popularity cratered in 2007.

What about mobilization for political violence? A team from the University of Maryland examined the goals of 102 grassroots Muslim organizations in North Africa and the Middle East and found that between 1985 and 2004 the proportion of organizations that endorsed violence dropped from 54 to 14 percent.

260

The proportion committed to nonviolent protests tripled, and the proportion that engaged in electoral politics doubled. These changes helped drive down the terrorism death curve in figure 6–11 and are reflected in the headlines, which feature far less terrorist violence in Egypt and Algeria than we read about a few years ago.

260

The proportion committed to nonviolent protests tripled, and the proportion that engaged in electoral politics doubled. These changes helped drive down the terrorism death curve in figure 6–11 and are reflected in the headlines, which feature far less terrorist violence in Egypt and Algeria than we read about a few years ago.

Islamic insularity is also being chipped at by a battery of liberalizing forces: independent news networks such as Al-Jazeera; American university campuses in the Gulf states; the penetration of the Internet, including social networking sites; the temptations of the global economy; and the pressure for women’s rights from pent-up internal demand, nongovernmental organizations, and allies in the West. Perhaps conservative ideologues will resist these forces and keep their societies in the Middle Ages forever. But perhaps they won’t.

In early 2011, as this book was going to press, a swelling protest movement deposed the leaders of Tunisia and Egypt and was threatening the regimes in Jordan, Bahrain, Libya, Syria, and Yemen. The outcome is unpredictable, but the protesters have been almost entirely nonviolent and non-Islamist, and are animated by a desire for democracy, good governance, and economic vitality rather than global jihad, the restoration of the caliphate, or death to infidels. Even with all these winds of change, it is conceivable that an Islamist tyrant or radical revolutionary group could drag an unwilling populace into a cataclysmic war. But it seems more probable that “the coming war with Islam” will never come. Islamic nations are unlikely to unite and challenge the West: they are too diverse, and they have no civilization-wide animus against us. Some Muslim countries, like Turkey, Indonesia, and Malaysia, are well on the way to becoming fairly liberal democracies. Some will continue to be ruled by SOBs, but they’ll be our SOBs. Some will try to muddle through the oxymoron of a Sharia democracy. None is likely to be governed by the ideology of Al Qaeda. This leaves three reasonably foreseeable dangers to the New Peace: nuclear terrorism, the regime in Iran, and climate change.

Other books

Our Man In Havana by Graham Greene

Reckless Disregard by Robert Rotstein

Infatuation: A Rebel Stepbrother Romance by Phoenyx Slaughter

RECKLESS - Part 3 (The RECKLESS Series) by Ward, Alice

Isabella's Heiress by N.P. Griffiths

A Bid for Love by Rachel Ann Nunes

The Severed Thread by Dione C. Suto

The Mysterious Governess (Daughters of Sin Book 3) by Beverley Oakley

Wild Bear (Bear Shifter Paranormal Romance) (Rescue Bears Book 2) by Scarlett Grove

The Boat to Redemption by Su Tong