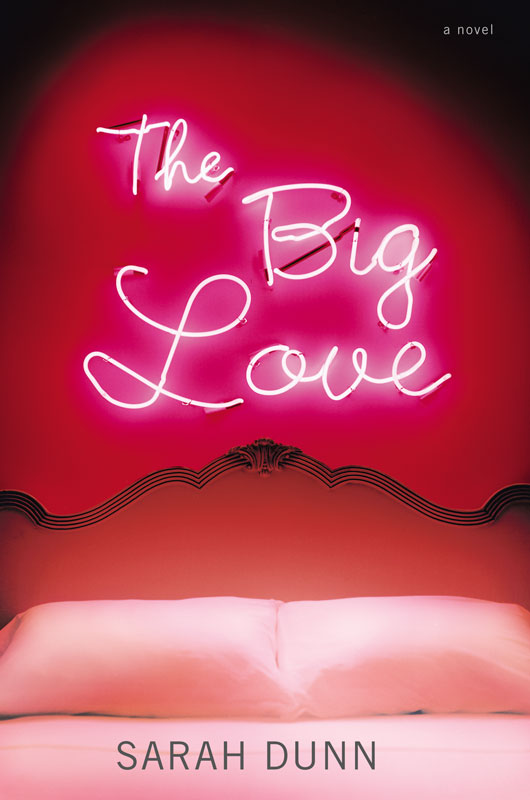

The Big Love

Copyright © 2004 by Sarah Dunn

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote brief passages in a review.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group, USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.hachettebookgroupusa.com

First eBook Edition: July 2004

The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-7595-1186-6

Contents

Click here for a preview of The Secrets to Happiness by Sarah Dunn

For my parents

Joe and Carolyn and Pete

And for David

T

O BE FAIR TO HIM, THERE IS PROBABLY NO WAY THAT TOM

could have left that would have made me happy. As it turns out, I’m in no mood to be fair to him, but I will do my best to be accurate. It was the last weekend in September. We were having a dinner party. Our guests were about to arrive. I ran out of Dijon mustard, which I needed for the sauce for the chicken, and so I sent my boyfriend, Tom—my “live-in” boyfriend, Tom, as my mother always called him—off to the grocery store to get some. “Don’t get the spicy kind,” was, I’m pretty sure, what I said to him right before he left, because one of the people coming over was my best friend, Bonnie, who happened to be seven months pregnant at the time, and spicy food makes Bonnie sweat even more than usual, and I figured that the last thing my dinner party needed was an enormous pregnant woman with a case of the flop sweats. It turned out, though, that that was not the last thing my dinner party needed. The last thing my dinner party needed was what actually happened: an hour after he left, Tom called from a pay phone to tell me to go ahead without him, he wasn’t coming back, he didn’t have the mustard, and oh, by the way, he was in love with somebody else.

And we had company! I was raised in such a way that you didn’t do anything weird or impolite or even remotely human when you had company, which is the only way I can explain what I did next. I calmly poked my head into the living room and said, “Bonnie, can you come into the kitchen for a second?”

Bonnie waddled into the kitchen.

“Where’s Tom?” Bonnie said.

“He’s not coming,” I said.

“Why not?” she said.

“I don’t know,” I said.

“What do you mean, you don’t know?”

“He said he’s not coming home. I think he just broke up with me.”

“

Over

the phone?

That’s impossible,” Bonnie said. “What were his exact words?”

I told her.

“Oh my God, he said that?” she said. “Are you sure?”

I burst into tears.

“Well, that is completely unacceptable,” Bonnie said. She hugged me hard. “It’s unforgivable.”

And it was unforgivable, truly it was. What made it unforgivable, as far as I was concerned, was not merely that Tom had ended a four-year-long relationship with no warning, or that he had done so over the telephone, or even that he had done it in the middle of a dinner party, but also this: the man had hung up before I had a chance to say so much as a single word in reply. That, it seemed to me, was almost inconceivable. What made it unforgivable as far as Bonnie was concerned was that she was sure the whole thing was nothing more than a ploy of Tom’s to keep from having to propose to me anytime soon. She actually articulated this theory while we were still hugging, thinking it would calm me down. “Men are trying to

avoid

getting married,” Bonnie said to me. “It doesn’t look fun to them.” She stroked my hair. “Their friends who are married look

beaten

down

.”

As if on cue, Bonnie’s husband Larry walked into the kitchen with a striped dishrag tucked into the waistband of his pants, carrying two plates of chicken marsala. Larry was very proud of his work with the chicken. When Tom hadn’t shown up on time with the mustard, Larry came up with the marsala concept, and made it by picking the mushrooms out of the salad. One thing I will tell you about Larry is that he cheated on Bonnie when they were dating, he cheated on her left and right in fact, but now here he was, father of two, maker of chicken marsala, the very picture of domestic tranquillity. He was beaten down, maybe; but he was beaten down and faithful.

“Tom’s not coming,” Bonnie said to Larry. “He says he’s in love with somebody else.”

“Who is he in love with?” Larry asked.

I knew who he was in love with, of course. I hadn’t even bothered to ask. He was in love with Kate Pearce. And I knew it! I

knew

it! Bonnie knew it too—I could tell by the look on her face. Bonnie and I had been conferring on the subject of Tom’s old college girlfriend Kate for quite some time, actually—ever since she had invited Tom out for the first of what would turn out to be a series of friendly little lunches, an event which incidentally happened to coincide with Bonnie’s acquisition of a Hands Free telephone headset. I mention the Hands Free telephone headset only because once she got it, pretty much all Bonnie wanted to do was talk on the phone.

“Tom started doing sit-ups last night during

Nightline,

” I told Bonnie during one of our phone calls. “Do you think that means anything?”

“Probably not,” Bonnie said.

“I don’t think a person all of a sudden starts doing sit-ups one day for no reason,” I said.

“A few weeks ago

Rocky

was on TNT, and the next day Larry set up his weight-lifting bench in the garage, so it could be nothing.”

“Did he say who?” Larry asked me. He put the chicken marsala down on the kitchen counter. “Did he tell you who he’s in love with?”

“He’s in love with Kate Pearce,” I said. There was something incredibly painful about saying that sentence out loud. I sat down at the kitchen table and quickly amended it: “At least, he thinks he’s in love with her.”

“It’s probably just a fling,” said Bonnie.

“Is that allowed?” said Larry.

“Of course it’s not allowed,” Bonnie said. “I just mean, maybe it’ll blow over.”

“You’ve never seen her,” I said. “She’s beautiful.”

“

You’re

beautiful,” Bonnie said, and then she reached across the table and patted my hand, which had the effect of making me feel not beautiful at all. Nobody ever pats a beautiful person’s hand when they tell them that they’re beautiful. It’s just not necessary.

My friend Cordelia came into the kitchen to see what was going on, and I took one look at her and burst into tears again. Cordelia burst into tears, too, and I got up from the table and we stood there on the gray linoleum for what seemed like forever, hugging each other the way you do when there is a dead relative involved. It wasn’t until much later that I found out that Cordelia, at that moment, thought there actually

was

a dead relative involved, and if she had known the true state of affairs she wouldn’t have cried nearly as much. She is very philosophical about matters of the heart, philosophical in the way that it’s only possible to be if you have been married once already and have absolutely no intention of doing so ever again. Cordelia was married to Richard for just under two years. They had what they deemed the usual problems, so they tried the usual solution: they went into therapy together. In the open, mutually accepting atmosphere fostered by their marriage counselor, Richard confessed to Cordelia that he was into amateur pornography. Cordelia thought, okay, not an ideal situation perhaps, but human sexuality is a complicated thing, and she could keep an open mind about her husband’s little peccadilloes. Thus emboldened, Richard went on to make what would turn out to be a pivotal clarification—he was, it turned out,

in

amateur pornography—and Cordelia realized that her mind was not that open.

“Well, he can’t break up with you over the phone,” Cordelia said, after Bonnie told her what had happened. “You live together. You own a couch together.”

“I’ve never told you this before,” Bonnie said to me, “but I’ve always hated that couch.”

“Tom picked it out,” I said. This made me start crying again. “I didn’t want him to think that moving in with me meant he wouldn’t get to pick out couches anymore.”

“That couch,” Bonnie said to Larry, “is why I don’t let you pick out couches.”

Shortly after that, Bonnie went out into the living room and sent the rest of the guests home. Then she and Larry cleaned up the kitchen so I wouldn’t have to wake up to a big pile of dirty dishes. Then Cordelia tucked me into bed with a bottle of wine. I told them I wanted to be alone, and the three of them finally left.

You should probably know that my first thought after I hung up the phone with Tom was that the thing with the ring was probably a mistake. What had happened was this: some months before, I happened upon a picture of an engagement ring I liked in a magazine, and I’m ashamed to tell you that I cut it out, and I’m even more ashamed to tell you that I did, in fact, slip it into Tom’s briefcase while he was in the bathroom taking a shower. I did not expect him to run out the next day and buy the ring. I thought it was information he might want to have on file at some indeterminate time in the future. When Larry asked Bonnie what kind of engagement ring she’d like, she said she didn’t want a solitaire, she wanted something different, and he said fine, different, I can do that, and Bonnie had a sudden flash of what he might come up with on his own—Larry being a man who once staple-gunned two old brown towels over his bedroom window and left them hanging there for four years—so she drew a picture on a cocktail napkin of a wide band of channel-set diamonds, and she wrote down the words

platinum

and

size six

and

BIG

and

SOON.

Larry dutifully took the napkin to a jeweler, and now Bonnie has on her finger something that looks like a very sparkly lug nut.

Of course, it’s possible I’m putting too much emphasis on the whole business with the ring, but I tend to zero in on one detail and skip over everything else. I always have. I took a life drawing class in college, and at the end of the first two-hour session the only thing I had on my sketchpad was an exquisite rendering of the model’s gigantic uncircumcised penis. But, well:

Obviously

I shouldn’t have put the picture of that ring in Tom’s briefcase.

Obviously

I should have put my foot down about the Kate stuff from the very beginning. I see that all clearly now. It just never entered my mind that Tom would actually have an affair! That’s a lie. It entered my mind constantly, but whenever I brought it up Tom would assure me I was being crazy. “I can’t live this way,” he’d say to me. “If you don’t trust me, maybe we should just end this now,” he’d say to me. And he’d be so calm and cool and logical that I’d think: He’s right, this is my stuff, this is my paranoia, this is happening because my father left when I was five, I was in an Oedipal stage, I have an irrational fear of abandonment, and I need to get over it. And then I’d be hit by a thought like, “Don’t crush the sparrow, hold it with an open hand; if it comes back to you it’s yours, if it doesn’t, it never was.” And I’d be fine, in a real Zen state, and then I’d try to remember where the sparrow thing came from, which would make me think of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s

The

Little Prince

even though there is actually no connection beyond a sort of dippy adolescent obviousness, which would make me think of Tom’s most cherished possession—a dippy hand-painted

Little Prince

T-shirt made for him in college by Kate, the same Kate he was busy lunching with—and I’d be right back where I started.

“Listen,” I said to Tom during one of our discussions about Kate. “I just don’t feel comfortable with you having lunch with your old girlfriend all the time.”

“I’m capable of being friends with a person I used to go out with,” Tom said. “You’re still friends with Gil.”

“First of all, I’m not still friends with Gil,” I said. “Second of all, Gil is gay, so even if I were still friends with him, it wouldn’t count, because he’s not interested in having sex with me. When he was having sex with me he wasn’t interested in having sex with me.”

“Kate has a boyfriend,” Tom said. I rolled my eyes. “She and Andre

live

together,” he said. I stifled a snort. “I’m not going to have this conversation anymore,” he said, and then he left to go play squash.