The Black History of the White House (12 page)

Read The Black History of the White House Online

Authors: Clarence Lusane

- Romona Riscoe Benson, interim president and chief executive officer of the African American Museum in Philadelphia;

- Charles L. Blockson, curator of the Charles Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University, and a founding member of Generations Unlimited;

- Michael Coard, a founding member of the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition;

- Tanya Hall, executive director of the Philadelphia Multicultural Affairs Congress;

- Edward Lawler Jr., a historian representing the Independence Hall Association;

- Charlene Mires, associate professor of history at Villanova University and editor of the Pennsylvania History Studies Series, representing the Ad-Hoc Historians;

- John Skief, chief administrative officer of the Harambee Institute of Science Technology Charter School;

- Karen Warrington, Representative Bob Brady's director of communications;

- Joyce Wilkerson, Mayor John Street's chief of staff.

57

Lawler's research not only sparked challenges to the building of the new structure, but also inspired black historians, activists, and political leaders to mobilize numerous community-based groups, including the Ad-Hoc Historians and the Avenging the Ancestors Coalition or ATAC (pronounced “attack”). The

group was created to “compel the National Park Service (NPS) and Independence National Historical Park (INHP) to finally agree to the creation of a prominent Slavery Commemoration as a key component of the President's House project.”

58

Protests, education campaigns, and negotiations by ATAC were key to winning funds allocated specifically for that purpose from the city and the National Park Service.

Carrying the struggle into the twenty-first century, ATAC also successfully lobbied to ensure that African Americans were employed in the construction of the project. In August 2009, Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter announced that 67 percent of the construction jobs through subcontracts were being awarded to minority- and women-owned businesses. In fact, the design of the project itself went to a black-owned architecture firm, Kelly/Maiello Architects & Planners, whose owner made every effort to include other minority firms in the work.

As of mid-2010, a number of issues remained unresolved as the effort to build a replica of the president's house and a memorial to the enslaved people who lived there moved forward. A dispute arose in the committee when historian Edward Lawler criticized three important inaccuracies in the design of the house: “The design incorrectly sited the front of the house, distorted the shape of a much-noted bow window designed by Washington, and placed a commemoration of the house slave quarters in the wrong spot.”

59

While not necessarily disagreeing with Lawler, the committee nevertheless went forward without revising the plan. For both legal and practical reasons, they argued that the agreed-upon design was still the best resolution.

ATAC's Michael Coard responded to Lawler and other critics: “There has also been criticism of the placement of the house's slave quarters. But if the quarters were placed exactly

where they stood more than 200 years ago, they would almost touch the new Liberty Bell Center, making the quarters impossible to enter and violating the Americans with Disabilities Act.”

60

He cautioned that “hyper-technical replication must sometimes give way to practical-minded accessibility” and that “Philadelphia is about to make history with this project. And the designers already made history by envisioning a powerful, important attraction that everyone in America and the world should want to see. But they won't see it if it's not practical.”

61

While the campaign to honor the men and women that Washington enslaved in Philadelphia was successful, a similar campaign has yet to unfold in the nation's capital, where dozens, if not hundreds, of slaves labored for U.S. presidents from James Madison to Zachary Taylor. These black people not only slaved in the White House but actually helped to build it. During the period that Washington and Adams were residing in Philadelphia, the difficult task of building a whole city, including the permanent home of the president, continued.

CHAPTER 3

On

and

With

Slavery

Some view our sable race with scornful eye,

“Their colour is a diabolic dye.”

Remember, Christians, Negroes, black as Cain,

May be refin'd, and join th' angelic train.

âPhillis Wheatley, the first black person to be published in the United States

1

Prelude: Peter's White House Story

Peter, or “Negro Peter” as he was sometimes listed on the payroll, must have been completely exhausted after working all day as a carpenter building the president's house in Washington, D.C., the structure that would one day be called the White House. The winter months are often very cold in Washington, D.C., as wind racing off the Potomac and Anacostia rivers drives the temperature down into single digits, and major snowstorms are not uncommon. Although as a carpenter Peter primarily labored inside, during the icy days of January 1795 the site of the half-built president's residence was certainly a frigid place to work. It was also likely that Peter did not get all the nutrition needed for such labor-intensive work. During the coldest days, he and the others forced to work there were likely underdressed

for the weather, and those who contracted a cold or the flu continued to work nevertheless. Suffering the freezing weather, long hours of toil, and meager meals alongside Peter were four other black carpentersâTom, Ben, Harry, and Danielâwho like Peter were also enslaved.

2

But these black men may have thought themselves more fortunate than others who were forced to slave in extreme conditions at the various stone quarries in and around Virginia. Those locations have been described as “snake-infested” and “swarmed with mosquitoes,” and the labor so arduous that each worker was given “a half-pint of whiskey per day to help them cope.”

3

This was spirit-killing work if such there ever was. Enslaved black men were ordered into the quarries from “can't see” to “can't see” to carry out the back-breaking tasks of digging, cutting, lifting, and hauling stone. Tons of the stone from which the U.S. capital is built, and which can still be seen today, got there via the slave labor of black men.

Although enslaved, Peter and the other black carpenters may have also thought themselves more lucky than the men, women, and children they saw each day being held in cages around the city or forced onto the auction block, many of whom were being sent to a life of misery on plantations in the dreaded Southern states of Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Louisiana. Among those in cages or being sold, some were being punished for attempting to escape, learning to read, or being thought to be agitators for freedom. Some had been free but were illegally abducted by slave catchers who destroyed the papers documenting their freedom, and were now selling them off to the highest bidder. The manacles holding these people were heavy, perhaps even rusted from having been exposed to all manner of climates. From the construction site of the president's residence, Peter and the others would have

witnessed these events on a daily basis. As writer Walter C. Clephane soberly states, “The District of Columbia became a great slave market.”

4

While forced to work at the construction site, the men would see and hear horrors all around them. An endless parade of shame coursed through the streets as human traffickers transported blacks on horse-drawn carts or ordered shackled men, women, and children into long chain-linked lines on their way to or from the auction block. At Lafayette Square, directly across from where the White House was being built, slave pens stood for all to see. When the pens were full, the city jails were used to hold overflow. In Alexandria, a part of the District until 1846, the firm of Franklin & Armfield became one of the largest dealers of abducted and enslaved people, selling by the 1830s as many as 1,000 black people per year.

5

At Third Street and Pennsylvania, a dozen or so blocks from the White House construction site, the St. Charles Hotel held enslaved people in basement cells. At Seventh Street and Pennsylvania, the most robust and active slave market in the city flourished. At an abode owned by James Birch known as the “Yellow House,” hundreds of individuals were treated no better than farm animals. The three-story building was bustling with activity and was considered one of the major East Coast hubs for the buying and selling of black people.

Describing his experience seeing a slave pen in Washington, D.C. in 1835, an English man wrote:

It is surrounded by a wooden paling fourteen or fifteen feet in height, with the posts outside to prevent escape, and separated from the building by a space too narrow to permit of a free circulation of air. At a small window above, which was unglazed and exposed alike to the heat of summer and the cold of winter, so trying to the constitution, two or three sable faces appeared looking out wistfully to while away the time and catch a refreshing breeze, the weather being extremely hot. In this wretched hovel all colors except white, both sexes, and all ages, are confined, exposed indiscriminately to the contamination which may be expected in such society and under such seclusion.

6

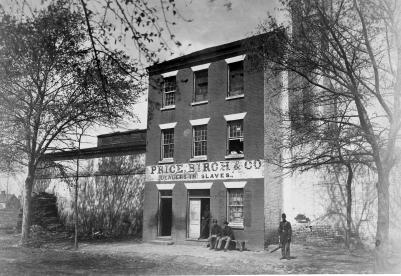

Slave pen, Alexandria, Virgina, circa 1863. In 1791, Alexandria was included in the area chosen by George Washington to become the District of Columbia.

Part of the ambient noise in Washington, D.C.'s streets was the constant wails, screams, and cries of the enslaved, their anguish omnipresent. While nearly all whites and a few free blacks were enjoying liberty from British control and constructing a new city to represent and govern their newfound freedom and democracy, others were brutally forced to live, toil, and die

in illiterate misery. So pervasive was the institution of slavery that most, if not all, of the hands that were building the White House were black hands. From their captive position trapped at the bottom of U.S. society, most of these people likely could not envision a time when they could enter the public buildings they were constructing as free and equal citizens, let alone as elected or appointed officials with authority over the inner workings of the nation. Was Peter one of those who believed that his destiny was to die enslaved, or did he imagine a future where he walked in the world as a free man?

As is the case for virtually all the black people who slaved to build the White House, not much is known about Peter's life and family. According to researcher Bob Arnebeck, Peter was likely sent to the District of Columbia by way of South Carolina with his owner, the Irish immigrant James Hoban, about whom a great deal is known.

7

Born in Desart, Ireland in 1762, James Hoban was living in Charleston, South Carolina, by his early twenties. After meeting President Washington in Charleston during the president's Southern tour in summer 1791, Hoban listened with interest when Washington mentioned the need for builders to help construct the nation's new capital. In 1792, he entered a design contest held to select the best architectural plan for building what would become the permanent residence and official office of all future U.S. presidents. Drawing from his Irish roots, Hoban rendered a plan inspired by Dublin's Leinster House and won the coveted $500 prize.

President Washington then tentatively hired Hoban to oversee the planning and construction of the building, and Hoban attended the groundbreaking ceremony. Washington liked Hoban and later wrote the commission in July 1792 to confirm his hire, stating, “He has been engaged in some of the first

buildings in Dublin, appears a master workman, and has a great many hands of his own.” By “hands,” Washington was likely referring to individuals Hoban was enslaving. Hoban's contributions to the city would go beyond his work on the White House and the Capitol. He would later become the first Superintendent Architect of the Capitol and be elected to the D.C. City Council. Unlike Peter's work, Hoban's has been remembered and honored in both Ireland and the United States.

Hoban and his assistant, Pierce Purcell, traveled to Washington, D.C. and began their work that year. They brought with them a number of the people they kept enslaved, including the carpenters Peter, Tom, Ben, and Harry, who were owned by Hoban, while the carpenter Daniel belonged to Purcell. According to the 1795 payroll records of the commission that oversaw the building of the new city, Peter and Tom were earning wages as much as those paid to the white indentured servants with whom they worked. This included the McCorkill brothers and Peter Smith, all of whom were white and whose contracts were owned by Hoban and Purcell.

In February 1795, Peter worked twenty-one days and earned “six pounds, sixteen shillings, & six pence” at a per diem rate of 6 shillings/6 penceâthe same rate being paid Peter Smith, a white servant who was indentured to Purcell. But the money Peter earned he did not get to keep. It went to James Hobanâthe man who enslaved him. Hoban and Purcell's enslaved black men appear to be the only ones ever hired as carpenters. George Washington's nephew, William Augustine Washington, had proposed to the commissioners to hire “twelve good Negro carpenters,” but they did not take him up on that offer.

From 1793 to 1797âafter which they and all other black carpenters were banned from working on the White HouseâPeter and the others were among the seventeen carpenters that

worked at the site and completed a significant amount of the interior carpentry work. Once finished, the White House was projected to be the largest residence in the country.

The black carpenters were banned by the commissioners as a consequence of a conflict between Hoban and another contractor. By late 1797, a rival Scottish contractor, Collen Williamson, submitted complaints to the commissioners regarding Hoban's use of black carpenters. Among the allegations were that black and Irish carpenters were getting paid too much relative to other carpenters, that Hoban was unfairly profiting from their labor, and that Hoban and Purcell were stealing building materials. Although there was little basis for the charges and it was clear that Williamson was driven by competitive revenge, the commission responded by ordering that “no Negro Carpenters or apprentices be hired at either of the public Buildings and that no Wages be allowed after that day to any white Apprentices without an especial order of the Board,” the public buildings meaning the White House and the Capitol.

8

As the new nation was presenting itself as being guided by the egalitarian principles of democracy, freedom, and justice, the home and office of the nation's president and commander in chief was being built, in part, with the slave labor of black people who were stripped of all rights. As far as the record shows, President Washington, who was in charge of making sure the project was completed, and Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who was responsible for the project's implementation, never spoke of or acknowledged this contradiction about the construction of the White House or the work that the black carpenters (and others) were doing.

If Not Slaves, Then Who? Enslaved and Free Labor Builds the Nation's Capital

The Federal City is increasing fast in buildings and rising in consequence; and will, no doubt, from the advantages given to it by Nature and its proximity to a rich interior country and the Western Territory, become the emporium of the United States.

9

âGeorge Washington, December 12, 1793

Enslaved labor built much of early America, particularly in the South. Indeed, almost every major building in every major city constructed in the pre-nineteenth-century era used slave labor in some capacity or was owned by a slaveholder. The list includes Philadelphia's Independence Hall, where both the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution were drafted, debated, and signed, and Boston's Faneuil Hall, given to the city by Peter Faneuil, who made his fortune in the triangular slave trade.

10

The list also includes the labor involved in the building and maintenance of the palatial plantation homes of George Washington at Mount Vernon, Thomas Jefferson at Monticello, and James Madison at Montpelier. The bodies, bones and muscles of enslaved blacks were used to construct nearly every major structure built in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the United States, but their labor has gone uncelebrated and largely undocumented. That this primary aspect of American labor history has been lost or forgotten does not mitigate the significance of recognizing the role black labor played in constructing the country's original state architecture, buildings and landscapes.

By the latter part of the eighteenth century, in Virginia and Marylandâthe two states in which white people enslaved the most blacksâit had become customary for slave owners to

hire out some of their blacks when it was profitable for them to do so. In Virginia, the state with the largest number of enslaved by a wide margin, the population of enslaved people had grown from a few hundred at the beginning of the eighteenth century to nearly 300,000 by the end of it. As historian Roger Wilkins notes, “By the time of the Revolution, 40 percent of all Virginians were black,” and 96 percent of that population was enslaved.

11

Maryland had more than 100,000 black people enslaved to whites.