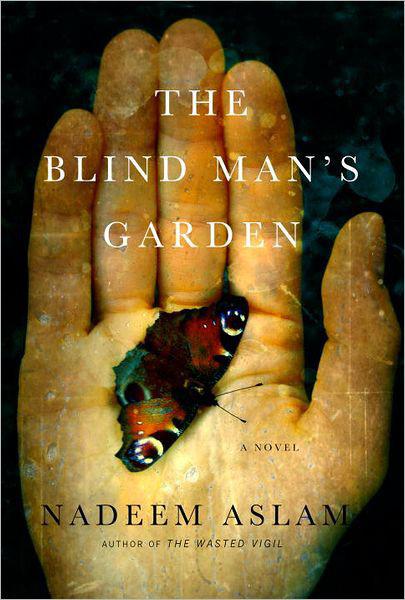

The Blind Man's Garden

The Blind Man’s Garden

NADEEM ASLAM

For Sadia and Nasir

Contents

FOOTNOTES TO DEFEAT

But a man’s life blood

is dark and mortal.

Once it wets the earth

what song can sing it back?

Aeschylus

1

History is the third parent.

As Rohan makes his way through the garden, not long after nightfall, a memory comes to him from his son Jeo’s childhood, a memory that slows him and eventually brings him to a standstill. Ahead of him candles are burning in various places at the house because there is no electricity. Wounds are said to emit light under certain conditions – touch them and the brightness will stay on the hands – and as the candles burn Rohan thinks of each flame as an injury somewhere in his house.

One evening as he was being told a story by Rohan, a troubled expression had appeared on Jeo’s face. Rohan had stopped speaking and gone up to him and lifted him into his arms, feeling the tremors in the small body. From dusk onwards, the boy tried to reassure himself that he would continue to exist after falling asleep, that he would emerge again into light on the other side. But that evening it was something else. After a few minutes, he revealed that his distress was caused by the appearance of the villain in the story he was being told. Rohan had given a small laugh to comfort him and asked,

‘But have you ever heard a story in which the evil person triumphs at the end?’

The boy thought for a while before replying.

‘No,’ he said, ‘but before they lose, they harm the good people. That is what I am afraid of.’

2

Rohan looks out of the window, his glance resting on the tree that was planted by his wife. It is now twenty years since she died, four days after she gave birth to Jeo. The scent of the tree’s flowers can stop conversation. Rohan knows no purer source of melancholy. A small section of it moves in the cold wind – a handful of foliage on a small branch, something a soldier might snap off before battle and attach to his helmet as camouflage.

He looks towards the clock. In a few hours he and Jeo will depart on a long journey, taking the overnight train to the city of Peshawar. It’s October. The United States was attacked last month, a day of fire visited on its cities. And as a consequence Western armies have invaded Afghanistan. ‘The Battle of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon’ is what some people here in Pakistan have named September’s terrorist attacks. The logic is that there are no innocent people in a guilty nation. And similarly, these weeks later, it is the buildings, orchards and hills of Afghanistan that are being torn apart by bombs and fire-shells. The wounded and injured are being brought out to Peshawar – and Jeo wishes to go to the border city and help tend to them. Father and son will be there early tomorrow morning, after a ten-hour journey through the night.

The glass pane in the window carries Rohan’s reflection – the deep brown iris in each eye, the colourless beard given a faint brilliance by the candle. The face that is a record of time’s weight on the soul.

He walks out into the garden where the first few lines of moonlight are picking out leaves and bowers. He takes a lantern from an alcove. Standing under the silk-cotton tree he raises the lantern into the air, looking up into the great crown. The tallest trees in the garden are ten times the height of a man and even with his arm at full stretch Rohan cannot extend the light beyond the nearest layer of foliage. He is unable to see any of the bird snares – the network of thin steel wires hidden deep inside the canopies, knots that will come alive and tighten just enough to hold a wing or neck in delicate, harmless captivity.

Or so the stranger had claimed. The man had appeared at the house late in the morning today and asked to put up the snares. A large rectangular cage was attached to the back of his rusting bicycle. He explained that he rode through town with the cage full of birds and people paid him to release one or more of them, the act of compassion gaining the customer forgiveness for some of his sins.

‘I am known as “the bird pardoner”,’ he said. ‘The freed bird says a prayer on behalf of the one who has bought its freedom. And God never ignores the prayers of the weak.’

Rohan had remarked to himself that the cage was large enough to contain a man.

To him the stranger’s idea had seemed anything but simple, its reasoning flawed. If a bird will say a prayer for the person who has bought its freedom, wouldn’t it call down retribution on the one who trapped and imprisoned it? And on the one who facilitated the entrapment? He had wished to reflect on the subject and had asked the man to return at a later time. But when he woke from his afternoon nap he discovered that the bird pardoner had taken their perfunctory exchange to be an agreement. While Rohan slept, he visited the house again and set up countless snares, claiming to Jeo that he had Rohan’s consent.

‘He told me he’ll be back early tomorrow morning to collect the birds,’ Jeo said.

Rohan looks up into the wide-armed trees as he moves from place to place within the garden, the thousands of sleeping leaves that surround his house. The wind lifts now and then but otherwise there is silence and stillness, a perfect hush in the night air. He is certain that many of the snares have already been activated and he cannot help but imagine the fright and suffering of the captured birds, who swerve and whistle delicately in the branches throughout the day, looking as though their outlines and markings are drawn with a finer nib than their surroundings, more sharply focused. Now he almost senses the eyes extinguishing two by two.

The bigger the sin, the rarer and more expensive the bird that is needed to erase it. Is that how the bird pardoner conducts his business? A sparrow for a small deception, but a paradise flycatcher and a monal pheasant for allowing a doubt about His existence to enter the mind.

He places his hand on a tree’s bark, as if transmitting forbearance and spirit up into the creatures. He was the founder and headmaster of a school, and his affection for this tree lies in its links with scholarship. Writing tablets have been made from its wood since antiquity, a use reflected in its Latin name.

Alstonia scholaris

.