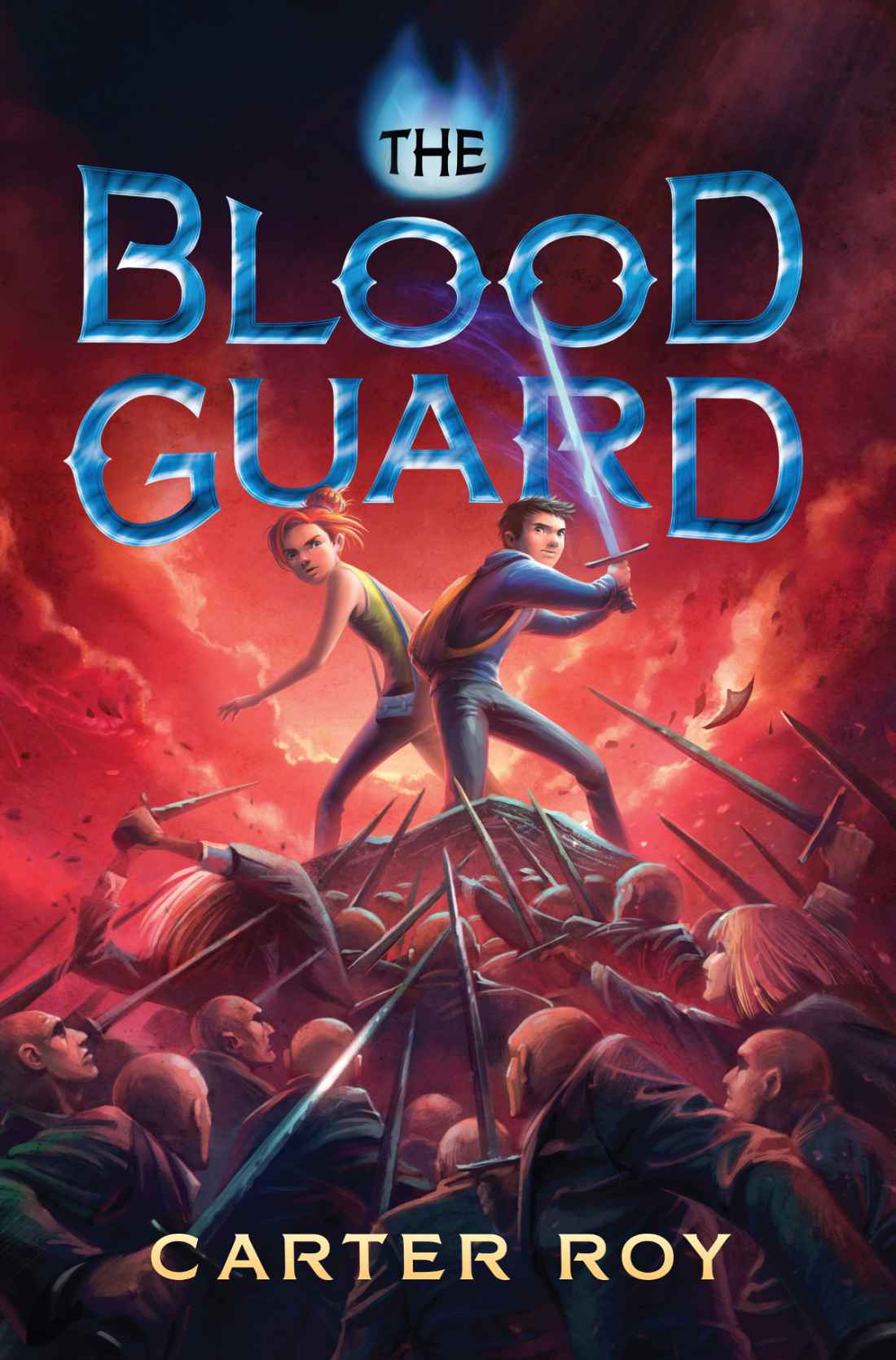

The Blood Guard (The Blood Guard series)

Read The Blood Guard (The Blood Guard series) Online

Authors: Carter Roy

PRAISE FOR

THE BLOOD GUARD:

“Wildly intense and deviously funny…has real heart as well as characters you’ll fall in love with. This is cool stuff, very cool stuff.”

—MICHAEL GRANT,

New York Times

bestselling author of

BZRK

and the Gone series

“The humorous and exciting start of a new trilogy. The stakes are raised with a startling revelation that will have readers eager for the next book.”

—

Kirkus Reviews

“Hits the ground running and doesn’t let up until it’s dragged you, gasping and astonished and delighted, over the finish line. Bound to get any kid who owns a flashlight in big trouble for reading under the covers well past bedtime.”

—BRUCE COVILLE, author of

Jeremy Thatcher, Dragon Hatcher

and

My Teacher Is an Alien

“The kind of witty, fleet-footed, swashbuckling adventure my twelve-year-old self would have gobbled up. Sure to be a hit with middle-grade adventure fans!”

—BRUCE HALE, author of the Chet Gecko Mysteries and

A School for S.P.I.E.S.: Playing with Fire

“Packed with breathless adventure, sword fighting, heartless betrayal, and car chases—but what I loved best about this book is that amidst all the fun it’s also pure of heart. I cannot wait to read the sequel!”

—SARAH PRINEAS, author of the Magic Thief series

“I love everything about this thrilling novel—its humor, its action, and

especially

Greta Sustermann. She is smart, sassy, vulnerable, and completely

kicks butt. I can’t wait to read the next book.”

—KATHRYN LITTLEWOOD, author of

Bliss

and

A Dash of Magic

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

While J. Seward Johnson, Jr.’s sculpture called

The Awakening

is very real, the author has taken liberties with its size, dimensions, and even current location. These days it can be found not at Hains Point in DC, but at National Harbor in nearby Maryland.

Text copyright © 2014 by The Inkhouse

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by Two Lions, New York

Amazon, the Amazon logo, and Two Lions are trademarks of

Amazon.com

, Inc., or its affiliates.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available upon request.

ISBN 9781477847251 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781477897256 (ebook)

Edited by Melanie Kroupa

Book design by Susan Gerber and Katrina Damkoehler

First edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for Beth, only everything

CONTENTS

C

HAPTER

2

: THE MOST DANGEROUS MOM ALIVE

C

HAPTER

3

: I TAKE A BATHROOM BREAK

C

HAPTER

4

: YOU’VE GOT TO PICK A POCKET OR TWO

C

HAPTER

6

: ALL MESSED UP AND NO PLACE TO GO

C

HAPTER

7

: THE RIGHT MAN FOR THE WRONG JOB

C

HAPTER

8

: WHEELS OF MISFORTUNE

C

HAPTER

11

: WE GET TAKEN FOR A RIDE

C

HAPTER

12

: THE PERFECT FAMILY GETAWAY

C

HAPTER

13

: A NOT-SO-GREAT ESCAPE

C

HAPTER

17

: THE SOUL OF THE MATTER

C

HAPTER

18

: WAITING FOR THE END OF THE WORLD

C

HAPTER

19

: JACK DAWKINS, FISHER OF WALLETS

C

HAPTER

20

: MY WAY ON THE HIGHWAY

C

HAPTER

21

: A THOUSAND LITTLE TESTS

C

HAPTER

22

: GRETA, PURE AND SIMPLE

C

HAPTER

23

: OGABE LOSES HIS HEAD

C

HAPTER

24

: DOWN A GIANT’S THROAT

C

HAPTER

26

: THE EYE OF THE NEEDLE

P

R

O

L

O

GU

E

:

PLAYING WITH FIRE

I

t wasn’t

me

who burned down our house.

I wasn’t even supposed to be there. I’d been sent home from school with a fever, and I’d taken a nap. Next thing I knew, flames were licking under my door and white smoke was filling the room. Pretty soon after that I was hugging the brownstone wall outside my third-floor bedroom window, wishing I’d put on some clothes first.

It was snowing. Hard. And the ledge I was standing on was slippery. Below me, the entire front of the house was ablaze, long tongues of fire stretching from every window.

So I went the other way. Up.

Scaling a burning building in a snowstorm in pajamas and bare feet? Not my idea of fun. But sometimes you don’t really have a choice.

Eventually, I reached the edge of our roof and hoisted myself over.

Safe

, I thought. The tarred surface was nice and warm under my feet. I almost felt like I could lie down and go to sleep again.

And then I snapped wide-awake.

It’s warm

, I thought.

In a snowstorm

.

I took off running.

I’d barely leaped across to the neighbor’s roof when our roof fell in. It made a plume of pretty sparks that shot up high into the air and then rained down on the neighborhood, the ash mixing with the snow.

I stood and watched, wondering what I was going to tell my mom.

It all seemed unrea

l

—

a

nd not just because I was feverish, barefoot, covered in soot, and wearing singed pajamas. But because our house was the only one in the row of brownstones to catch fire.

A professional job

, the investigators called it later, but that was just a guess. They never found evidence of arson. And they couldn’t figure out a motive for why my parents or I would want to destroy our own home. So after a while, they gave up and labeled it a freak accident.

We moved to a new place in a new neighborhood in a totally new state. I went to a new school with new kids who didn’t accuse me of being the boy who played with fire.

I figured I’d survived the worst moment of my life. Nothing else that happened to me could ever come close to being as awful as that one day.

But I was wrong. Boy was I ever.

C

H

A

PT

E

R

1

:

TRUST NO ONE

C

all me Ronan.

It’s my middle name. My first is

Evelyn

and my last is

Truelove

, which is kind of a spectacular bummer on all fronts, because I’m a guy. My mom’s uncle Evelyn was from Great Britain, where I guess that name doesn’t sound weird for a boy. He had a house on a huge wooded lake in northern Michigan. So because my mom liked paddling a canoe there when she was nine, she gave me a first name that sounds like a girl’s.

I can’t even begin to explain how wrong this is.

My name gets me a whole lot of attention. By the time I started kindergarten, I was used to the teasing; it was the fights that were new. This enormous kid named Dennis Gault decided he wanted my lunch box. “Give it here,

Evelyn

,” he said. Dennis was only in second grade, but he looked like a giant, with fists as big as cantaloupes.

It wasn’t much of a lunch bo

x

—

j

ust a cheap plastic

Dragon Ball Z

thin

g

—

b

ut I wasn’t about to hand it over. “Don’t call me Evelyn,” I replied.

I got home an hour later, lunch box gone, blood running from my nose. I don’t know what I thought my mom would do. Call the principal and complain, maybe.

Instead, she enrolled me in judo. “It’s time you learned how to fight,” she said.

“I don’t

want

to fight!” I said.

“Cut the whining. This will be good for you.”

I was

five

.

I’m thirteen now, and because of my mom, I’ve taken everything from judo to aikido, Krav Maga to kendo. (Kendo is a Japanese martial art in which you beat up your opponent with a long stick. It looks like good times until someone starts whacking you back.) And Mom didn’t just sign me up for self-defense. She’s had me take classes in swing dance and horseback riding and wilderness survival training an

d

—

w

ell, she makes sure that I am always busy.

Thanks to all the classes, these days I know how to take care of myself in a fight. These days, no one bullies me. And no one calls me Evelyn.

Most of the time no one calls me anything at all.

I don’t have all that many friends at my new school. When we moved to Connecticut after the fire, the kids already had their friendships locked down. It didn’t help much that I’m always skipping off after school to take weird classes in fencing or metalworking or advanced gymnastics. I mean, imagine explaining to your new maybe-friend that you can’t hang out and play PS3 because you have to pull on a leotard and perfect your dismount from the parallel bars. Pretty soon no one invites you to anything.

Gymnastics was where I was headed the afternoon when everything started. School had just let out for the day, and the halls were buzzing. I stood at my locker and listened to the kids around me talk about an end-of-year pool party that a popular eighth grader was throwing that weekend. Just about everyone had been invited.

Everyone but me.

I swapped my algebra textbook for social studies, then stuffed it into my backpack on top of my leotard.

“You going to hit Cassie’s swim thing on Saturday?” Nathan Romaneck was in my Honors classes. He was a little bit of a dwee

b

—

h

is crew cut and old T-shirt made him look like an eight-year-ol

d

—

b

ut he was one of the few kids who was sort of kind of like a friend.

“Lost my invite,” I said.

“I wasn’t invited, either,” he said, shrugging. “But I’m going anyway. The crowd there will be big enough that we’ll be invisible.”

“I’d love to go,” I started to say, “but I’v

e

—

”

“

—

g

ot trapeze class or whatever until eight. And then fencing Sunday morning,” he said. “I know: Your mom calls the shots and you have to do what she tells you. Want to get into a good college, blah-blah-blah.”

“It’s not like that, Nate,” I said, but we both knew he was right. My mom kept me aggressively overscheduled. I wasn’t always crazy about it, but I also didn’t mind. You don’t care as much about being an outsider if you’re always busy.

I closed my locker and was fighting my way through the flood of kids in front of the building when I heard someone call my name.

“Evelyn Ronan Truelove!”

Only one person calls me that.

My mom.

She was leaning against her yellow VW bug, parked in clear violation of the

TEACHERS ONLY

sign. She wore a blue men’s dress shirt with the sleeves rolled to her elbows and paint-spattered blue jeans, and her long black hair was tied back in a messy ponytail. My mom stands out in a crowd, mostly because of the burning intensity of her eyes: When she is looking at you, it’s like the sun shines on you alone. No one and nothing else exists.

“Are you here to drive me to gymnastics?” I asked as I walked over. It was strange to see her her

e

—

s

he works full-time as a museum curator and isn’t usually done early enough to pick me up from school. I swung my backpack into the VW and climbed in. “Because I’m good with walking there, honest.”

“Special treat,” she said, glancing quickly to either side. I looked, too, but there was nothing much to see, just the usual end-of-the-school-day business: Hundreds of kids pouring out in a noisy flood, a line of yellow buses idling in the far lot. “Buckle up, sweet child of mine,” Mom said. “We are in a massive hurry.”

As I pulled the door shut, she threw the bug into drive and gunned out of the lot. A few sharp turns, and we were shooting around the back of the school and into the valley toward downtown.

“Gymnastics is the other way. And aren’t you driving kind of fast?”

“Thanks for the directions, Christopher Columbus. But you’re not going to class.” Mom’s eyes kept darting to the rearview mirror as she swerved past slower cars.

“Excellent!” I couldn’t hide my joy; I hated wearing spandex. “I mean, I’m not?”

“Nope.” There was something new in her face that showed in the crease of her brow and the grim flat line of her lips: fear.

“What’s wrong?”

Without explaining, she said, “Hold tight,” stood on the brakes, and cranked the wheel hard left. The tires shrieked and skidded, and the world outside the window whirled as the car spun around 180 degrees. I thought I was going to throw up.

Now we were facing the other direction. On a one-way street.

“That move,” she explained, accelerating straight into oncoming traffic, “is called a bootlegger. One day I’ll show you how to do it.”

“Mom!” I shouted. “What are you doing?”

“Trying to lose our tail,” she said, biting her lower lip and leaning forward. She jockeyed the gearshift and swung the car around a honking dump truck. Directly behind it were two dark-red SUVs barreling down on us, one in each lane.

“And this,” Mom said, stomping on the gas and driving straight at them, “is called chicken.”

At the last minute, the two SUVs swerved up on the sidewalk and thundered past on either side. I looked out the back window and saw them both turn around.

“Why are they chasing you?” I asked.

“Us,” she said, squeezing my arm. “They’re after

us

. And they’re chasing us because they want to capture and probably kill us, honey. But I’m not going to let them.”

“Come on, Mom.” I laughed like this was a bad joke. “They want to

kill

us?” When she gave me a quick look, I saw she was serious.

She blew through a red ligh

t

—

m

ore honking, more squealing of brake

s

—

a

nd made a hard left into the entrance of Brickman Nature Preserve, where she’d enrolled me in a competitive tree-climbing class last fall. She zoomed along the scenic drive that wound uphill through the shadowy groves, leaning forward over the wheel.

“This street dead-ends at the top,” I reminded her. Behind us I caught a flash of sunlight off a windshiel

d

—

o

ne of the red SUVs coming after us.

Once we reached the tiny parking area at the summit, Mom pulled up to the curb and threw the VW into neutral. She left the engine idling. Below us stretched the rolling green hillside, and far off in the hazy distance, the cluster of buildings that was downtown Stanhope, Connecticut, the city we’ve called home since Brooklyn.

The park was crowded with bikers and people walking dogs and little kids playing. A long flight of concrete steps went straight down the middle of the grassy hill to another parking lot and a little lake, the water a silvery glint barely visible past the trees.

Through the VW’s open windows we could hear engines gunning up the hill behind u

s

—

t

he SUVs. Whoever they were, they were still on our tail. There was only one exit: the road we’d taken here.

We were trapped.

“Will you tell me now what’s going on?” I asked, reaching for the door handle.

“We’re taking the stairs. You’re going to want to hold on, honey.” She stomped on the gas.

I hollered as we caught air off the top landing. The engine revved hard as the wheels left the pavement, and I felt myself rise off the seat against the shoulder belt, saw a V of birds beat their wings against the bright blue sk

y—

And then the car crashed down onto the steps.

The doors caught on the bannisters and the side-view mirrors popped off. The air bags blew out and slammed me back against the seat.

Somehow my mom kept driving.

The car was a tight fit between the railings, but not so tight that we got stuck. Reaching around the air bag, Mom kept working the gearshift and the gas, and the bug bolted forward, bouncing and rattling and banging as it hit every one of the steps.

At the landing halfway down, we slowed. The air bags had deflated some, but now everything in the ca

r

—

i

ncluding me and my mo

m

—

w

as covered with a powdery gray dust that stank like new rubber. “Are you crazy?” I asked, coughing. “Can we just stop and tal

k

—

”

But we were off again. With an enormous scrape, we began jouncing down the second long flight.

All this time, my mom was jabbing at the hor

n

—

a

s though anyone could miss the car screeching its way down the steps. Through the windshield I watched people dive over the bannisters, screaming as they ran.

At last, with a teeth-snapping bang, we reached the foot of the stairs, and Mom brought the car to a stop. “Are you okay, honey?” she asked, reaching over and patting my shoulder and face. “Talk to me, Ronan.”

“I’m fine,” I said. I wiped my face clean with my hoodie, then leaned out the window. The sides of the bug were crumpled, and steam was billowing out from beneath the hood. The engine made little ticking sounds as a puddle of liquid slowly spread out from under the engine. “Mom, what are you doing?” I asked. “We could have just

died

.”

But her head was turned away. She was staring in the other direction, back the way we’d come.

At the top of the hill, stark against the bright sky, one of the red SUVs had tried the same stunt we’d just pulled but had been pinned by the railings. The other SUV was parked alongside, its grill flush against the railing. Five men and a woman, all wearing dark-blue suits, stood watching from above.

“Who are those people?” I asked.

“Bad guys,” my mom said. “It’s complicated.” Her voice sounded remarkably calm, but when she put the car back into drive, her hand shook. “Someone trashed the hous

e

—

l

ooking for somethin

g

—

a

nd now your dad has…gone missing.”

That was the final piece, the thing she said that convinced me my mom was delusional. She announces we’re being pursued by people who want to kill us.

Sure

. She risks our lives and trashes the VW.

Okay

. But the news that my fathe

r

—

n

erdy, quiet, absent Dad, who is the comptroller (whatever that means) for a multinational conglomerate (whatever that is) has been kidnapped?

No way

.

“Why would anyone want to kidnap Dad?” I asked. “He’s like a fancy accountant.”

She didn’t reply. In silence we tooled along the broad concrete walkway that ran by the lake, following its gentle curves toward the parking lot on the far side.

“Maybe it was

him

,” I insisted. “Maybe he was looking for something, and he was just sloppy. Did you think of that?”