The Blue Light Project (2 page)

Read The Blue Light Project Online

Authors: Timothy Taylor

PART ONE

“Keep up the good work! Keep up the good work, you beautiful, beautiful young artists!”

Anonymous dancing woman, January 2008

WEDNESDAY

OCTOBER 23

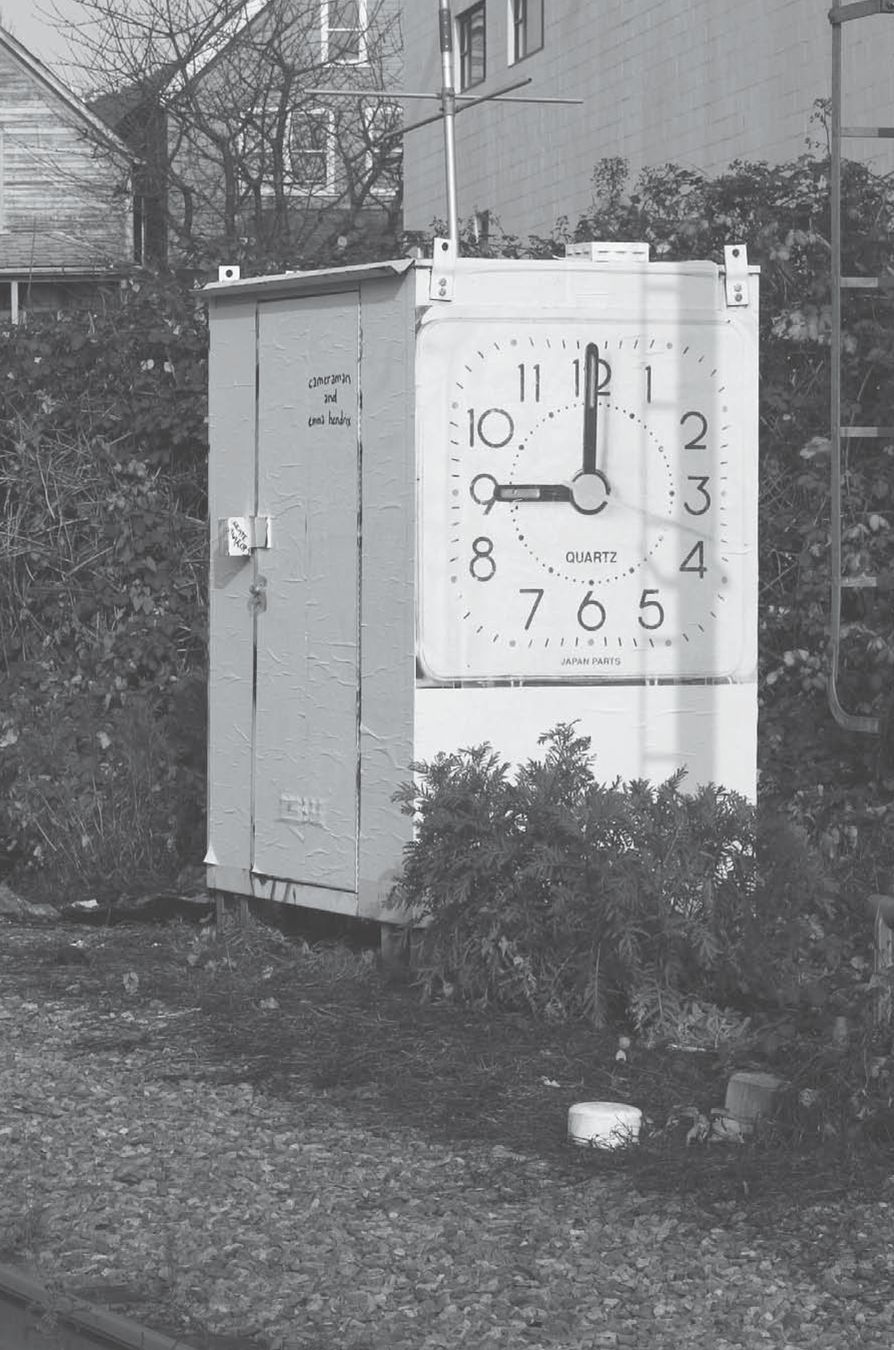

EVE RAN THE STREETS in the earliest hours of Wednesday morning, a lean shape in black. Through the riverside neighborhoods, the Flats, River Park, Stofton, the lower Slopes. She slipped through on silent shoes, nothing to hear but her breath. She surveyed the walls. The posters and billboards, the cloud of advertisement hanging over every space in the city. But more recently, another phenomenon too: heaving seas of urban art.

Posters, photographs, paintings, sheets of words. Graffiti seemed to be the smallest part of it these days. Eve liked the long landscape banners in the alleys of the lower Slopes and Stofton, stencils of wildflowers and fields of long grass. Always one bunny, stamped in the corner. Or the poster series she’d seen in River Park that read:

You’ll Find It Where You Last Saw It.

These words drawn in felt pen and ballpoint over a picture of keys, loose change, cigarette lighters, little love hearts and peace signs. Once, far east into the warehouse district, deep into a run, Eve was brought to a halt in front of an entire wall papered over with these. A hundred missing objects, ideals, notions. She stood looking up, breathing hard, hands to her hips, smiling at

this crazy thing. If it didn’t make any particular sense, Eve thought it made a kind of super-sense, responding to impulse logic just beyond the rational. And that made her think of herself at a younger age, ready to burst into action, to proceed in the face of disagreement. Sure of her heart.

You’ll Find It Where You Last Saw It.

These words drawn in felt pen and ballpoint over a picture of keys, loose change, cigarette lighters, little love hearts and peace signs. Once, far east into the warehouse district, deep into a run, Eve was brought to a halt in front of an entire wall papered over with these. A hundred missing objects, ideals, notions. She stood looking up, breathing hard, hands to her hips, smiling at

this crazy thing. If it didn’t make any particular sense, Eve thought it made a kind of super-sense, responding to impulse logic just beyond the rational. And that made her think of herself at a younger age, ready to burst into action, to proceed in the face of disagreement. Sure of her heart.

Fast run, long run, rest day. Stairs, rest day, short run. Then, on the seventh day, the night run. Eve started as the light failed. She ran the bridges, the worn eastern suburbs. She ran the river and the inner city. She ran into the late night, into the early morning, and Nick would complain about her coming home so late.

Eve liked the photographs too. She saw shots of urban distress, textures, faces, construction sites, dumpsters. These were postered up near the places or objects they depicted, on a nearby wall, hoarding, bus shelter, train bridge, mailbox. Why here? Why anywhere? Most people had no idea these images existed at all. But Eve also knew you had to close your eyes not to see them.

Eve knew this art existed. She also knew that her estranged brother, Ali, had once been part of this world. And gripped hard by a recent inspiration, she was looking for him. So she ran the parts of the city he’d favored in those last years of contact between them. Seven, eight years ago, far too long. She remembered a wiry reed of a kid, urban explorer, wall climber, roof jumper. When they were teenagers, Eve had followed him everywhere. Up the East Shore radio tower once, highest point in the city at the peak of the ridgeline north of the river—350 feet. A four-sided tapering Eiffelized structure in steel. Up a dozen crisscross flights of stairs, up into the freezing night. She faltered at the final length of it, where the tower grew so narrow that you had to thread your way up thirty feet of ladder through a cylindrical lattice to the final platform, which Eve could see swaying against the blackness, nestled among the stars. Suddenly the whole business seemed crazy. And she froze, couldn’t move a muscle. Tears squeezed out of her eyes and seemed to

ice on her cheeks in the wind that whipped the deck on which she stood.

ice on her cheeks in the wind that whipped the deck on which she stood.

Then Ali came back and slipped a lean and muscular arm around her shoulders. She warmed immediately with his touch, with his words. “Don’t worry, E. We’ll stay here. I’ll stay with you. Look at that. Look at the view. We’re above it all.”

And he’d been so right, saying so. Back then, they had truly been above it all.

EVE RAN AND RAN. Always alone, although never feeling alone. Where she last knew Ali had lived, in the oldest and poorest parts of the city, the streets kept you company. Eve would stop and show people the wrinkled photograph she carried. Her brother standing on a flat roof, hands on his hips, painted in orange streaks and blue shadows by the sunset off to the west. A man with the scent of boyhood still on him. So handsome. Eve loved the picture and showed it around with a trace of pride. “I’m looking for this good-looking guy who happens to be my brother. He’d be about ten years older now. Around thirty-six. Have you seen him?”

She ran with a water bladder strapped between her shoulder blades. Six months back at the running program, after letting it go for several years, Eve was closing in on something she remembered, a feeling like she could run forever.

“His name is Ali,” Eve would say. Some old guy smoking on the concrete steps out front of a corner store still open at midnight. Sitting right where he’d been sitting for years.

“Ali as in Muhammad?”

“He was named after Muhammad Ali, in fact,” Eve would say. “My father was a big fan.”

“You Muslim?”

“Secular humanist. How about you?”

“I believe in God and Allah and all those. You sure you want to be running down here this hour?”

Dark streets, shining alleys. Eve alone and yet in the company of the city, its wall art, the shifting energy of its sidewalks where crowds gathered after midnight around the neon hum of the convenience stores. There was crime in the riverside neighborhoods, Eve knew. Stofton especially. But she never felt afraid, even miles away from the neighborhood where she lived in the western reaches of the city. Miles from its quiet sleep and private security SUVs, its shingled roofs and motionactivated lights that blinked on nervously over the wide lawns.

One night, just off Sixth Street in Stofton, not far from an intersection that served as an open-air market for drug dealers, Eve came across two young men putting up a poster on a plywood hoarding over an abandoned storefront. There was a crowd watching. Two dozen people standing in the low light, the wafting smells of the sewer and the riverfront. A bearded man sat on an overturned milk crate nearby. Somebody lay at his feet covered in a blanket, coughing and heaving in the chill. The poster was six feet wide and at least that high. It was made with dozens of single sheets of paper, each one a panel of the larger image, pasted up onto the plywood with a brush and a pot of glue. The final image only slowly made itself plain: a close-up photo of two plastic figurines blown to life size, gymnasts with their backs arched and hands extended in a flourish over their heads. There were large bold letters across the bottom of the poster. When the last panel went up, the young men stepped back and everyone could see that the words were

Freedom Is Slavery.

And the crowd began to cheer. The man with the beard yelled: “That is black and white!” Another man said: “Right on!” And a woman who had been standing nearby, tightly gripping two plastic bags full of clothes, put her things down and danced up the sidewalk, singing: “Keep up the good work! Keep up the good work, you beautiful, beautiful young artists!” Eve herself standing with a hand to her mouth now, a lump forming in her throat. The reaction rippled around her, so genuine and so passionate, that it infected Eve

too. The woman twirling away up the street past a silent police car bathed in silver street light.

Freedom Is Slavery.

And the crowd began to cheer. The man with the beard yelled: “That is black and white!” Another man said: “Right on!” And a woman who had been standing nearby, tightly gripping two plastic bags full of clothes, put her things down and danced up the sidewalk, singing: “Keep up the good work! Keep up the good work, you beautiful, beautiful young artists!” Eve herself standing with a hand to her mouth now, a lump forming in her throat. The reaction rippled around her, so genuine and so passionate, that it infected Eve

too. The woman twirling away up the street past a silent police car bathed in silver street light.

Onward. West out of Stofton. West through River Park, the Flats, along the boulevards that funneled into the West Stretch. She increased her pace, not to hurry but to hear her body in its solitary rhythms and pulses. She shone with sweat, with pleasure, thinking again of the two young men and their poster. The woman and her dance and how her feet had scuffed the pavement in circles, again and again.

Beautiful, beautiful.

Down into the quieter winding streets, the looping concentration around West Slopes, then West Lake. Nick would be long snoring by now, lying on his back under his sleep-mask with his earplugs. Otis deep in the murmuring disquiet of his young man’s dreams. Oats, they called him, his boyhood nickname although he was seventeen already. Young man enough to be aware of Eve and his father together and to poorly conceal his bemusement at that.

Down into the quieter winding streets, the looping concentration around West Slopes, then West Lake. Nick would be long snoring by now, lying on his back under his sleep-mask with his earplugs. Otis deep in the murmuring disquiet of his young man’s dreams. Oats, they called him, his boyhood nickname although he was seventeen already. Young man enough to be aware of Eve and his father together and to poorly conceal his bemusement at that.

Down towards Angus Lake and towards the house, which had been Nick’s parents’ house, which is how Eve always read the lawns and the low expanse of building in those moments. She lived there. But it was

his

high square hedge.

His

family oaks and flower beds. Cored out by her run, dangerously emptied, with still no news of Ali, Eve felt now more alone for the effort of looking than she’d been when she started.

his

high square hedge.

His

family oaks and flower beds. Cored out by her run, dangerously emptied, with still no news of Ali, Eve felt now more alone for the effort of looking than she’d been when she started.

It was never her house at the end of a long night run.

THE REFRIGERATOR WOKE FIRST, the television on its aluminum face winking to life, a burble below. A long-familiar tune: war and financial turmoil. There were websites that could be consulted for maps and graphs, videos and the best advice of experts.

Eve hummed “Satellite of Love” while she dressed.

She knocked on the door of Nick’s bathroom to let him know she was up, fed the old Alsatian, Hassoman, with his creaking hips and unfixed glaucomic stare. A golden capsule of glucosamine with the

organic kibble. Then she went into the big kitchen at the back of the house to find Otis at the table already, hunched in front of his netbook, expression rapt, features luminous with screen light in the half-dark, playing MoleChess™.

organic kibble. Then she went into the big kitchen at the back of the house to find Otis at the table already, hunched in front of his netbook, expression rapt, features luminous with screen light in the half-dark, playing MoleChess™.

Eve pulled up the blinds and flicked on the lights over the counter. “I hope at least you’re winning.”

He said: “Morning, Champ. Do I lose?”

“You want some breakfast?”

“Gotta finish this one.”

“Oats, you own the site,” Eve said. “You could adjust your score.”

Molechess.com

. The noble game bent to suit suspicious times. You owned a piece on your opponent’s side, activated for a single move of your choosing. So were games upended by black bishops slaughtering their own, knights rampant behind the lines, queens killing their own kings at the crucial turn. Was it more exciting with traitors?

. The noble game bent to suit suspicious times. You owned a piece on your opponent’s side, activated for a single move of your choosing. So were games upended by black bishops slaughtering their own, knights rampant behind the lines, queens killing their own kings at the crucial turn. Was it more exciting with traitors?

“Not traitors, Champ,” Otis once explained, with the deliberate patience of a smart teenager accustomed to adults falling behind. “Here we are dealing with something more like a system imperfection. Like a program flaw or a defect. Which people really seem to like.”

They certainly seemed to. Thousands of people were paying members of the site. Eve was forced to reflect on occasion what it meant that Nick’s kid was well on his way to becoming independently wealthy, before university. He was, Eve supposed, enacting his family genes, moneywise at the level of their amino acids. In three generations of Nick’s family: a mill owner, a land developer turned wine writer, and now an online-gaming entrepreneur whose skin complexion had not yet cleared. Eve didn’t feel quite so competent being between careers herself, between phases somehow. Out of phase. She felt it in the morning especially, when the blinds first went up and the horizon presented itself. A person should be brimming with anticipation at that point in the day, possibility undiluted by fatigue or

disappointment. Eve missed that feeling, having known it once. The morning pull of a purposeful heart.

disappointment. Eve missed that feeling, having known it once. The morning pull of a purposeful heart.

Other books

Summer Wine: Taste of Seduction, Book 1 by Jess Dee

Why Darwin Matters by Michael Shermer

Devils Among Us by Mandy M. Roth

The Veteran by Frederick Forsyth

Don't... by Jack L. Pyke

Agent in Training by Jerri Drennen

Paper Faces by Rachel Anderson

Charcoal Tears by Jane Washington

Burn by Sean Doolittle

Crossings by Stef Ann Holm