The Boarded-Up House (5 page)

Read The Boarded-Up House Online

Authors: C. Clyde Squires

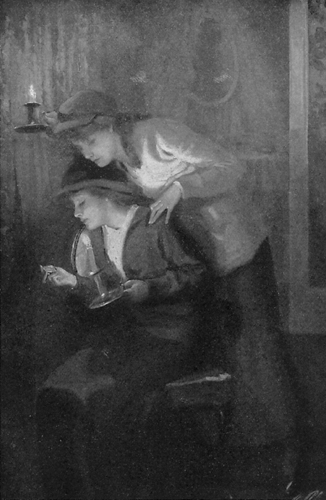

“I'm going to poke among these ashes,” she announced. “A lot of things seem to have been burned here, mostly old letters. Who knows but what the key may have been thrown in too!” She began to rake the dead ashes, and suddenly a half-burned log fell apart, dropping something through to the bottom with a “chinking” sound.

“Well, what do you suppose that can be?” queried Cynthia

“Did you hear that?” she whispered. “Something clinked! Ashes or wood won't make that sound. Oh, suppose it is the key!” She raked away again frantically, and hauled out a quantity of charred debris, but nothing even faintly resembling a key. When nothing more remained, she poked the fragments disgustedly, while Cynthia looked on.

“See there!” Cynthia suddenly exclaimed. “It isn't a key, but what's that round thing?” Joyce had seen it at the same moment and picked it upâa small, elliptical disk so blackened with soot that nothing could be made of it till it was wiped off. When freed from its coating of black, one side proved to be of shining metal, probably gold, and the other of some white or yellowish substance, the girls could not tell just what. In the center of this was a curious smear of various dim colors.

“Well, what do you suppose that can be?” queried Cynthia.

“I can't imagine. Whatever it was, the fire has pretty well finished it. You can see that it must have been rather valuable once,âthere's gold on it. Here's another question to add to our catechism: what is it, and why was it thrown in the fire? Whatever it was, it doesn't help much now. If it had only been the key!âGood gracious! is that a rat?” Both girls jumped to their feet and stood listening to the strange sounds that came from under the valance hanging about the bottom of the great four-poster bed. It was a curious, intermittent, irregular sound, as of something being pushed about the floor. After they had listened a moment, it suddenly struck them both that the noise was somehow very familiar.

“Why, it's Goliath, of course!” laughed Cynthia, “This is the second time he has scared us. He has something under there that he's playing with, knocking it about, you know. Let's see what it is!” They tiptoed over and raised the valance.

Cynthia was right. Goliath was under the bed, dabbing gracefully with one paw at something attached to a string or narrow ribbon. Despite the rolls of dust that lay about, Joyce crawled under and rescued it. She emerged with a flushed face and a triumphant chuckle. “Goliath beats us all!! He's made the best find yet!”

“Is it the key?” cried Cynthia.

“No, it's this!” And before Cynthia's astonished eyes Joyce dangled a large gold locket, suspended on a narrow black velvet ribbon. In the candle-light the locket glistened with tiny jewels.

“Do you recognize it?” demanded Joyce.

“Recognize

it? How should I ?”

“Why, Cynthia! It's the very one that hangs about the neck of our Lovely Lady in the picture down-stairs!” It was, indeed, no other. Even the narrow black velvet ribbon was identical.

“She must have dropped it accidentally, perhaps when she took it off, and it rolled under the bed. In her hurry she probably forgot it,” said Joyce, laying it beside the curious disk they had raked from the fireplace. “Isn't it a beauty? It must be very valuable.” Cynthia bent down and examined both articles closely.

“Did you notice, Joyce,” she presently remarked, “that those two things are exactly the same shape, and almost the same size?”

“Why, so they are!” exclaimed Joyce. “Oh, I have an idea, Cynthia! Can we open the locket? Let's try.” She picked it up and pried at the catch with her thumb-nail. After a trifling resistance it yielded. The locket fell open and revealed itselfâempty. Joyce took up the disk and fitted it into one side. With the gold back pressed inward, it slid into place, leaving no shadow of doubt that it had originally formed part of this trinket.

“Now,” announced Joyce, “I know! It was a miniature, an ivory one, but the fire has entirely destroyed the likeness. Question: how came it in the fire?” The two girls stood looking at each other and at the locket, more bewildered than ever by this curious discovery. Goliath, cheated of his plaything, was making futile dabs at the dangling velvet ribbon. Suddenly Joyce straightened up and looked Cynthia squarely in the eyes.

“I've thought it out,” she said quietly. “It just came to me. The miniature was taken out of the locketâon purpose,

to destroy

it! The miniature was of the same person whose picture is turned to the wall down-stairs!”

JOYCE'S THEORY

C

YNTHIA, what's your theory about the mystery of the Boarded-up House?”

The two girls were sitting in a favorite nook of theirs under an old, bent apple-tree in the yard back of the Boarded-up House, on a sunny morning a week later. They were supposed to be “cramming” for the monthly “exams,” and had their books spread out all around them. Cynthia looked up with a frown, from an irregular Latin conjugation.

“What's a

theory?”

“Why, you know! In Conan Doyle's mystery stories

Sherlock Holmes

always has a âtheory' about what has happened, before he really knows; that is, he makes up a story of his own, from the few things he has found out, before he gets at the whole truth.”

“Well,” replied Cynthia, laying aside her Latin grammar, “since you ask me, my theory is that some one committed a murder in that room we can't get in, then locked it up and went away, and had the house all boarded up so it wouldn't be discovered. I've lain awake nights thinking of it. And I'd just as lief

not

get into that room, if it's so!”

Joyce broke into a peal of laughter. “Oh, Cynthia! If that isn't exactly like you! Who but you would have thought of such a thing!”

“I don't see anything queer about it,” retorted Cynthia. “Doesn't everything point that way?”

“Certainly not, Cynthia Sprague! Do you suppose that even years and years ago any one in a big house like this could commit a murder, and then calmly lock up and walk away, and the matter never be investigated? That's absurd! The murdered person would be missed and people would wonder why the place was left like this, and theâthe authorities would get in here in a hurry. No, there wasn't any murder or anything bloodthirsty at all; something very different.”

“Well, since you don't like

my

theory,” replied Cynthia, still nettled, “what's yours? Of course you

have

one!”

“Yes, I have one, and I have lain awake nights, too, thinking it out. I'll tell you what it is, and if you don't agree with me, you're free to say so. Here's the way it all seems tome:

“Whatever happened in that house must have concerned two persons, at least. And one of them, you must admit, was our Lovely Lady whose portrait hangs in the library. Her room and clothes and locket show that. She looks very young, but she must have been some one of importance in the house, probably the mistress, or she would n't have occupied the biggest bedroom and had her picture on the wall. You think that much is all right, don't you?” Cynthia nodded.

“Then there's some one else. That one we don't know anything at all about, but it is n't hard

to guess that it was the person whose picture is turned to the wall, and whose miniature was in the locket, and who, probably, occupied the locked-up room. That person must have been some near and dear relation of the Lovely Lady's, surely. Butâwhat? We can't tell yet. It might be mother, father, sister, brother, husband, son, or daughter, any of these.

“The Lovely Lady (I'll have to call her that, because we don't know her name) was giving a party, and every one was at dinner, when word was suddenly brought to her about this relative. Or perhaps the person was right there, and did something that displeased her,âI can't tell which. Whatever it was,âbad news either way,âit could only have been one of two things. Either the relative was dead, or had done something awful and disgraceful. Anyhow, the Lovely Lady was so terribly shocked by it that she dismissed her dinner party right away. I don't suppose she felt it right to do it. It was not very polite, but probably excusable under the circumstances!”

“Maybe she fainted away,” suggested Cynthia, practically. “Ladies were always doing that years ago, especially when they heard bad news.”

“Good enough I” agreed Joyce. “I never thought of it. She probably did. Of course, that would break up the party at once. Well, when she came to and every one had gone, she was wild, frantic with grief or disappointment or disgust, and decided she just

couldn't

stay in that house any longer. She must have dismissed her servants right away, though why she didn't make them clear up first, I can't think. Then she began to pack up to go away, and decided she wouldn't bother taking most of her things. And sometime, just about then, she probably turned the picture to the wall and took the other one out of her locket and threw it into the fire. Then she went away, and never, never came back any more.”

“Yes, but how about the house?” objected Cynthia. “How did that get boarded up?”

“I have thought that out,” said Joyce. “She may have stayed long enough to see the boarding up done, or she may have ordered some one to do it later. It can be done from the outside.”

“I think she was foolish to leave all her good clothes,” commented Cynthia, “and the locket under the bed, too.”

“I don't believe she remembered the locketâor cared about it!” mused Joyce. “She was probably too upset and hurried to think of it again. And I'm sure she lay on the bed and cried a good deal. It looks like that. Now what do you think of my theory, Cynthia?”

“Why, I think it is all right, fineâas far as it goes. I never could have pieced things together in that way. But you haven't thought about who this mysterious relative was, have you?”

“Yes, I have, but, of course, that's much harder to decide because we have so little to go on. I'll tell you one thing I've pretty nearly settled, though. Whatever happened, it wasn't that anybody

died!

When people die, you're terribly grieved and upset, of course, and you

may

shut up your house and never come near it again. I've heard of such things happening. But you generally put things nicely to rights first, and you don't go away and forget more than half your belongings. If you don't tend to these things yourself, you get some one else to do it for you. And one other thing is certain too. You don't turn the dead relative's picture to the wall or tear it out of your locket and throw it into the fire. You'd be far more likely to keep the picture always near so that you could look at it often. Isn't that so?”

“Of course!” assented Cynthia.

“Then it

must

have been the other thing that happened. Somebody did something wrong, or disappointing, or disgraceful. It must have been a dreadful thing, to make the Lovely Lady desert that house forever. I can't imagine what!”

“But what about the locked-up room?” interrupted Cynthia. “Have you any theory about that? You haven't mentioned it.”

“That's something I simply can't puzzle out,” confessed Joyce. “The Lovely Lady must have locked it, or the disgraceful relative may have done it, or some one entirely different. I can't make any sense out of it.”

“Well, Joy,” answered Cynthia, “you've a theory about what happened, and it certainly sounds sensible. Now, have you any about what relative it was? That's the next most interesting thing.”

“I don't think it could have been her father or mother,” replied Joyce, thoughtfully. “Parents aren't liable to cause that kind of trouble, so we'll count them out. She looks very young, not nearly old enough to have a son or daughter who would do anything very dreadful, so we'll count

them

out. (Isn't this just like the âelimination' in algebra!) That leaves only brother, sister, or husband to be thought about.”

“You forget aunts, uncles, and cousins!” interposed Cynthia.

“Oh, Cyn! how absurd! They are much too distant. It

must

have been some one nearer than that, to matter so much!”

“I think it's most likely her husband, then,” decided Cynthia. “He'd matter most of all.”

“Yes, I've thought of that, but here's the objection: her husband, supposing she had one, Would probably have owned this house. Consequently he wouldn't be likely to allow it to be shut up forever in this queer way. He'd come back after a while and do what he pleased with it. No, I don't think it was her husband, or that she was married at all. It must have been either a sister or brother,âa younger one probably,âand the Lovely Lady loved herâor himâbetter than any one else in the world.”

“Look here!” interrupted Cynthia, suddenly. “There's the easiest way to decide all this!”