The Bolter (33 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

Then, suddenly, David and Gee had had a father again, and a mother too—although a different one from the figure who had bounded through their nursery before. She had been “Mummie.”

1

Barbie was most definitely “Mother.”

Then, almost as soon as they had arrived, Euan and Barbie had vanished again, taking the boys’ nanny, Miss Jeffreys, with them. In her place had come Nanny Sleath. Nanny Sleath had brought up Barbie, and Barbie’s brother and sisters—the entire Lutyens family—and now she was going to bring up Barbie’s stepsons too.

David and Gee had stayed in Eastbourne for three more weeks. On Friday, 30 April, ten days before Euan and Barbie’s wedding, Nanny Sleath and the two nursery maids who trotted behind her, each clutching a boy quite firmly, piled themselves and David and Gee onto a train for London, arriving, wrote Euan in his diary, at four-thirty. And then, as though discharging a duty before they again vanished for months, Euan and Barbie took the boys to a society doctor, who declared himself “delighted with them in every way.”

Within a couple of hours Barbie and Euan had bundled the boys onto an overnight train to Scotland—“the kids went off to Kildonan by the 7:20”—leaving the newly engaged couple free to enjoy their wedding and a two-month-long trip abroad.

By lunchtime on 1 May, David and Gee were standing in front of a gleaming new building-in-progress that promised to be as large as a seaside grand hotel and staffed on the inside by columns of black-dressed and white-capped housekeepers and housemaids, footmen and bootboys, cooks and undercooks, scullery maids, and even a tweeny

2

or two. The grounds, too, were packed with an army of retainers in brown and green: gardeners and gamekeepers, woodmen and kennel keepers.

This, the Kildonan House that Idina had designed, was to be their new home. The only Wallace family staff missing were Euan’s valet, Wooster, and Barbie’s lady’s maid, Miss Knight. They were, of course, accompanying Euan and Barbie on honeymoon.

Kildonan was heaven for little boys.

3

There was a vast amount of space to run around in and, unlike an Eastbourne boardinghouse, no wrinkled faces clearly wishing they were not there. There were lawns, with a climbing tree neatly split into two so that each of them could take a trunk and race the other as high as they could go. There was a wide river reached by climbing over a low fence and crawling through the long grass to the edge, where they could lie, dipping their hands in the water. There was other water too. A brook across the lawn and, behind the house, a burn—“a burrrrn,” said MacDowell (pronounced McDool), who ran the grounds. This stream also ran along one edge of the lawn but, for the sake of a few feet of extra grass, an enticingly long, dark tunnel had been engineered over it and turf laid on top.

Up behind the tunnel and the burn were a tennis court, an orchard—it was too early in the year for apples when they arrived—a nursery garden straight out of

Peter Rabbit

and acres and acres of a very deep, very dark wood in which they built houses “out of sticks and bracken & played Red Indians all the afternoon,” wrote Barbie’s sister Ursula in her diary of a visit to the house.

4

Euan and Barbie came; and stayed. For two long months the house bulged with their friends; then in late September the household packed up, piled back on the train, and headed for their new London home. This was a Mayfair town house, filled with some of the same faces that had been at Kildonan and, of course, Nanny Sleath. From time to time Euan and Barbie wafted through their new nursery and the schoolroom in which a governess came to give them lessons. After two Christmases, Easters, and summers at Kildonan, a new mewling bundle of baby boy joined them in the nursery, and two little black Shetland ponies arrived in the stables—“too sweet for words, and the children are marvellous on them,” wrote Ursula.

5

Within months, David and Gee had been sent away to boarding school: “Barbie and I chose Heatherdown,” wrote Euan, “with 90 boys, as 150 is too many.”

For David and Gee, leaving for boarding school had been the beginning of the rest of their boyhood: three terms a year of joshing and teasing and freezing on rugby pitches and burning on cricket fields and Latin and arithmetic and parsing and Greek with ink-stained fingers. Then it was back to Kildonan for the summer hols, to a house jammed

with braying red faces and tweed bottoms for the grouse, and again at Christmas, this time for the pheasant. Too young to shoot, they instead loaded guns on the moors, tied on flies on the riverbanks and cast a line or two. When it rained they ran inside. There were 250 feet of carefully thought-out passageways on each floor, with a single corner to navigate at speed.

From now on Easter was spent with Nanny Sleath by the sea, at Bognor or Brighton or Poole or Eastbourne again, or back at Frinton, on the other side of the country. It must have seemed that whenever they came home there was a new face in the nursery: brothers one, two, and three. Johnny came first, Peter immediately after. Then there was a gap before Billy, who was not, as it had been hoped, a girl. But very much the youngest, and the only one not in an almost-twin pair, he was kept as spoilt as only the baby of a family can be. At the other end of the family, David and Gee clung to each other, inseparable: “When one of us was punished, and kept indoors for the day, the other stayed in with him.”

6

IT WAS IN THE SUMMER OF 1931

that David first began to feel anger with the world. He was sixteen years old, his parents had beautiful homes, limitless funds, and ranks of servants. He himself was now at Eton, bound in stiff collars and ancient traditions designed to insulate him from the world outside. But he had only to read a newspaper or open his eyes on the Windsor streets and see humans reduced to refuse, trying to sell anything they could with the fragments of dignity that remained to them. For almost two years businesses had been folding, the survivors supported only by the mercy of their lenders. Through June and July, the lenders themselves were imploding, throwing not just their debtors’ but their own employees onto the end of the winding, ragged queues waiting for the dole, waiting for soup, waiting for change.

The halfhearted new National Government under Ramsay MacDonald wasn’t enough for David.

7

Quite the opposite. His father was put back into the government. His parents’ friends continued to loll around drawing rooms, leaning back on the sofas, their own or their neighbor’s pearls twisted in one hand, the stem of a champagne glass in another. Outside there was still rampant unemployment. David did not hesitate to tell both his parents and their bejeweled friends that he did not believe it was right. He rapidly gained a reputation, wrote Euan, for being “socialistic.”

8

By the end of 1931 even Euan and Barbie were beginning to feel pinched. “World financial conditions,” wrote Euan in his diary, “resulted in the loss of 40 per cent of our income and in October we had to make drastic household economies: everyone is in the same boat, & most people worse off than we are. All the same it is impossible to go on for many years when expenditure exceeds income by 60%.” Family economies were made: the previous year the Wallaces had spent Christmas at Malaga and visited Cannes, Rome, and Vienna. In 1932, however, “we did hardly any travelling & spent more time than usual in London,” wrote Euan. They paid off as many servants as they could bear (so adding to the ranks of the unemployed), leaving a “reduced staff” that “worked very well.” This saved Euan “£4000 on general expenditure” alone—a sum equivalent to a couple of hundred thousand today—of which “£1000 represented no foreign expeditions,” though “no foreign expeditions” still meant “a week at Corne d’Or in July” for Barbie and a “week-end at Le Touquet” in Normandy for Euan.

That year David’s anger subsided a little, at least as far as Euan noticed. He “became much more sociable and less socialistic and everyone likes him enormously.” It was his last year at Eton. He had been busy. A year younger than his classmates, David had still been House Captain; he had his School Certificate to sit and then the Oxford entrance exam. He left “with the most wonderful reports as to character from GWL [his housemaster] and the Headmaster.” On the basis that David and Gee’s “motor bikes caused no casualties” so far, at Christmas Euan “gave them a small car.”

Then David had gone abroad for the rest of the academic year, until he started at Oxford. He left for Paris in January. But, within a few weeks, he felt “not very happy.”

9

Barbie urged him to give it more time. He did, and then went on to Germany for another three months, which he did not enjoy either.

10

But Euan, busy with his political career—he was a junior defense minister, Civil Lord of the Admiralty, and that year, 1933, “foreign affairs (France & Germany & Japan) very awkward at times”—was too preoccupied to notice otherwise. David’s sojourns abroad, he wrote, “were both very successful.”

The week before David went up to Oxford, Euan left for a two-month tour of the “China and E. Indies Stations.” Barbie was busy with the younger ones, so David took himself up to Oxford alone.

OXFORD IN THE EARLY THIRTIES

was a maelstrom of ideology, emotion, and beliefs that the world was broken and only an extreme

course of action could mend it. And David was caught up in its currents. Oddly, nobody in the family saw him from the day he went to the day he returned home at the Christmas vac. By then wearing clothes that looked as though they hadn’t been washed since he had left, he had come to his decision to live on the other side of the moral world as a temperate, sexually abstinent, Christian Socialist priest.

11

David scrawled in the diary Gee gave him for Christmas that year—not a leather-covered Smythson’s but a two-shilling, cardboard workingman’s diary, one that Gee knew David would accept—that abstinence did not come easily: “Another great failure. Changing, was nude before glass and as usual, after a few games, slipped straight into bed and making bloody mess and as usual being livid with self after.”

12

But, notwithstanding the difficulty of attaining his objective, the rift between David and his family broadened. When Barbie sacked a servant, Arthur, for visiting the doctor in working hours, David picked up

Equality

, by R. H. Tawney. “It is extremely interesting. Marked a few passages. The rich are all kindness until their claims are questioned, when they become like a lion. The value of the working class movement is not to adjust the present order, redistribute wealth more equally, but to substitute the standard of men for that of wealth, gain that usual respect, which is owing to them and they do not get (e.g. Mother and Arthur).”

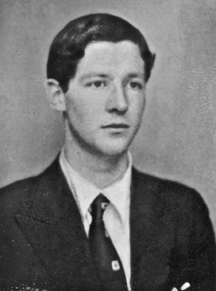

Idina’s son David Wallace

This time Euan noticed that his son was at odds with the life he had been brought up in. Within days David recorded that his father had “told all the ancestors that I am going into the Church.”

In January David returned to a university full of “ju-jitsu,” being invited to dons’ rooms for late-night whiskies “which I made water,” and the Labour Club. He went to talks and wrote afterward in his diary: “Aneurin Bevan spoke. Repetitive and tiresome manner, demagogue and quite interesting.… Walked back with Crofts. Tells me he has no confidence in working class. Comes of working class, which I did not know. I must talk to him more.”

But, clearly now realizing that David needed some attention, that spring term the family made an effort to visit him at Oxford.

David’s first visitors were Nanny Sleath and his brothers John and

Peter. They arrived at midday one Saturday in late January, stayed for lunch and a short walk, and left at three. Having observed her former charge in his student habitat, a few days later Nanny Sleath sent “another pullover from Self-ridges and said send her the yellow one to wash,” wrote David.

Next came his beloved brother Gee. He stayed an entire weekend: two full days alone together after their first whole year apart, since David had left school the Christmas before. It was “grand” to see Gee, “lovely having” him, he wrote.

Finally, on 19 February, on the way back from what was now widely called a “weekend” of hunting and golfing, Euan and Barbie decided to drop in, leaving their car to be driven on to London ahead of them. They lunched in David’s room, the college butler Adams rustling up a “last minute” meal.